Photograph: Public Domain

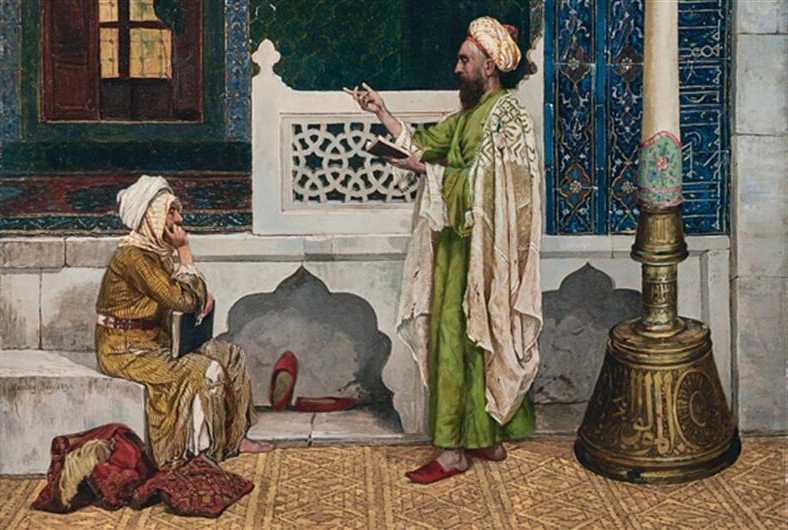

The path of love

“I did not think that I, a recovering existentialist,

would find myself one day slipping through the back door of Islam.”

LIKE A WHIRLING dervish, Revolutions of the Heart is the dance of a master writer and poet. Turning effortlessly and elegantly through the literary, cultural and spiritual, Yahia Lababidi, Lebanese-Egyptian-American, has borne his heart of all that he cherishes and holds sacred in life.

In this month’s guest post for The Culturium, Yahia offers us his deeply intimate meditations on the nature of the human condition through this exquisite compendium of essays, conversations and reviews. Whether it be Western philosophy, books, art, mysticism or Middle Eastern politics, his lyrical reflections distil the very essence of who he intrinsically is.

Author of nine critically acclaimed books of poetry and prose as well as three celebrated collections of aphorisms, Yahia’s work has been featured across the media and generously endorsed by President Obama’s inaugural poet, Richard Blanco. Nominated for a Pushcart Prize three times, he has also participated in numerous international poetry festivals throughout the world, his writing translated into several languages, including Arabic, Hebrew, Slovak, Spanish, French, Italian, German, Dutch, and Swedish.

Photograph: Public Domain

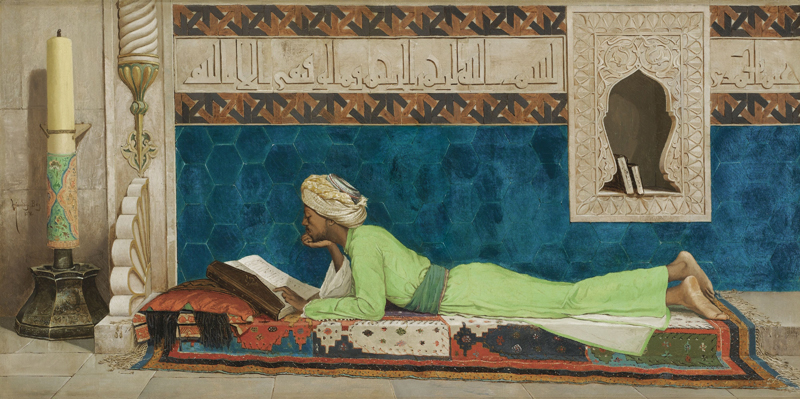

The Books We Were

“Certain cherished books are like old loves.

We didn’t part on bad terms,

but it’s complicated,

and would require too much effort to resume relations.”

If one’s first love is for Letters, people tend to come second (or possibly third). Yes, books are ink-and-paper relationships that can supplement and, at times, displace flesh-and-blood relations.

Such was my breathlessly intense, and evidently unhealthy, understanding of literature as an impressionable, voracious teenager. I read to get drunk and, to paraphrase Baudelaire, hoped to stay that way. A clutch of slim volumes altered my intellectual landscape and, at the risk of melodrama, saved my life. Past the intoxicating, escapist, aesthetic experience (style always mattered for me), these early loves knew me before I knew myself and confessed my secrets—speaking the yearnings of my still-inchoate soul far more eloquently than I could ever dream at that tender age. Sensing my desperation and need, I believed these books opened themselves up to me so that they were a more real and alive world than any other I inhabited.

The first, which made me suspect I might (want to) be a writer was Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Its relentless cleverness made for a heady ride, and I might have underlined every other line while highlighting the rest. By donning a mask of brilliant wit, Wilde seemed to have split himself in two and outdistanced his pain. This was a trick worth learning, my sixteen-year-old self intuited wordlessly, as was his apparently effortless knack for pithy summary. “I summed up all things in a phrase, all existence in an epigram: whatever I touched I made beautiful,” Wilde would go on to say in De Profundis, (which I devoured shortly afterwards, along with all his immodest utterances, in various genres). Yet, fond as I am of this early crush, I cannot bear to return to Wilde’s Gray. Past his glittering style, I find the cynicism suffocating. As Franz Kafka is supposed to have said to Gustav Janouch of Wilde’s work: “It sparkles and seduces, as only a poison can … It is dangerous because it plays with truth. A game with truth is always a game with life.” Then, there was Kafka, and his sublime self-loathing and life-recoil. He also came to me in my teens, when I was particularly susceptible to that volatile cocktail. Those hallucinatory short stories, especially his “A Hunger Artist” hit me like a dark epiphany: “I have to fast, I can’t help it. It is just that I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, I would have stuffed myself like you or anyone else.” Afterwards, came the exquisite masochism of his diaries, which I inhaled like a guilty pleasure, and concluded with his choice aphorisms. Of all his work, actually, it is the aphorisms that I can return to, which are, somehow, greater than the sum of the man and his torment.

Before I turned twenty, I was to encounter the love of my life—the one that would set my world spinning and take me nearly two decades to recover from: Nietzsche. His Zarathustra combined everything I needed to hear at the time: rebellious philosophy, stylish nihilism, vicious humour, and something akin to prophecy. He spoke the soul-splitting contradictions I hardly had words for—“Body and soul, I am more of a battlefield than a human being”—and, in my intemperate enthusiasm, I can say that, for the next decade or so, he was nearer and dearer to me than any living soul. Incredible, now, to think it!

Nietzsche handed me over to that other hysterical prophet: Dostoevsky. And, if memory serves correctly, I was so caught up in his Notes from Underground that I hardly noticed that the train I was riding had derailed. When I did (because everyone else was panicking and scrambling to get off the tram), I proceeded to disembark, in measured pace, without tearing my eyes off his delirious pages. And so it was: one Existentialist horror writer after another kicked me around for a bit then passed me, the besotted lover, off to their buddies to have some violent fun with.

Which is why when, belatedly, I recovered my senses and bearing, I had to set these seductive invalids aside for some time. For, just as they’d oxygenated my days, they’d also left me in a moral, spiritual daze. I felt I’d just barely managed to escape their clutches and could not afford to flirt with their frailties any longer—from fear I might be dragged to that treacherous space where they initially found me. They began to all seem like otherworldly, gilled creatures thrown upon the earth, gasping for a breath from their home atmosphere. I just couldn’t bear to pity any more suffering—each one, forever, on the verge of nervous collapse. I’d combed their letters, I’d inhabited their journals, I’d read between their lines. Quite simply, I had to keep these once too-dear books at a distance, as I was afraid of what echoing responses they might draw from me.

I was able to formally say goodbye to these formative influences in a book of conversations: The Artist as Mystic. In this love letter to my early masters (including Kierkegaard, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and the usual suspects), I was finally able to see, with the 20/20 vision of hindsight, that what I was attracted to in these dark thinkers was an anguished yearning, a longing to utter what’s ineffable: in short, the Light. It’s just that with my night vision, at the time, I could only take so much glare, and could not find my sustenance in sunlit spaces . . . yet.

“At the end of my suffering / there was a door,” writes Louise Glück in The Wild Iris. That door would lead me to poetry that was at the threshold of revelation. The sort of poetry that had set me alight in Eliot’s Four Quartets and Rilke’s Duino Elegies (two loves from my past that I can and do return to). And, past poetry, further along on the other side of that door, I made a somewhat destabilizing, liberating discovery: I found that not only did I care far less for the tyranny of the mind and its chew toys, which I previously cherished, but “literature” also seemed to matter much less. To quote Rumi, who spoke of the limitations of poetry when he had become a celebrated poet: “What, after all, is my concern with Poetry? In comparison with the true reality, I have no time for poetry. It is the only nutrition that my visitors can accept, so like a good host I provide it.”

And, just like that, my early love for Western philosophical literature slowly came to be replaced by Eastern mysticism. First, through that little inexhaustible marvel of a book, the Tao Te Ching, bursting with fruitful paradoxes and then, in quick succession, mystics of all stripes: Buddhist, Christian, Sufi. Maybe this sounds odd, but through the eyes of love (quietly gazing past the loud surface differences) I find that I can see the luminous spirit of Rumi in Nietzsche, only stunted. I recognize that I am drawn to the captivating contradictions in both, the serious play and their radical ecstasy. But I see the example of scholar-become-poet, who then goes on to make of his entire life a work of art, more beautifully and spiritually realized in the Persian master.

“What you are seeking is also seeking you,” Rumi says. Certain cherished books, like old loves, find and transform us at decisive stages of our lives. Thus, they remain emblazoned on our minds and hearts, whether we like it or not. And when we must address these emissaries of the past (as I find that I am doing, now) we should try to speak of them with the respect and tenderness befitting a ghostly self. If I might be permitted one parting quote from another Sufi mystic, Al-Ghazali, “Only that which cannot be lost in a shipwreck is yours.” The rest is flotsam.

Photograph: Public Domain

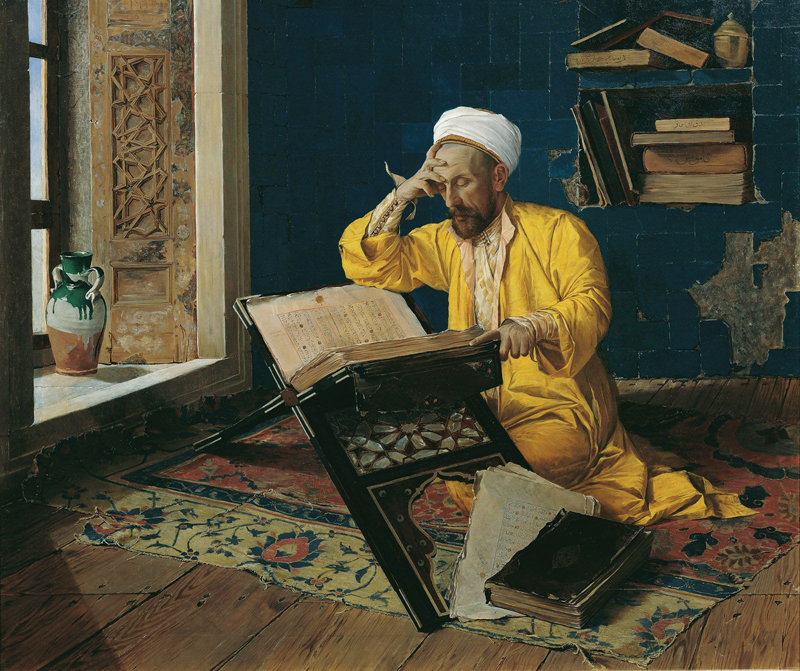

What Makes for Good Conversation?

In our increasingly polarized world, I’ve begun to ask myself what makes for a good conversation, what is the essential criteria for an engaging exchange. Is it being heard, learning something new, human connection, or something else, altogether? With most of us living behind screens, I’m afraid that we might be getting rusty at the vital art (and sport) of face-to-face, civilized exchange. As someone who lives for and through good conversations, here are some reflections from my personal experience of what I think contributes to valuable human interaction.

“Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity,” said Simone Weil, French philosopher, mystic and political activist. This is doubly so, in our hurried and distracted times. To truly listen—with our eyes, ears, mind and heart—is the first step. Conversation is not a series of interrupted monologues, where we are impatiently waiting for the other person to stop talking so that we can sound off. Interested people are more interesting to know and good listeners make for better talkers.

Hear and try to take in the other person with genuine interest. Try to consider how they might have arrived at the positions they hold, for better or worse. Even if their views might seem odious to you, try and see yourself in the other person, and the other person in you. Now, go further; flex your spiritual muscle, and seek the Divine in them. If we are able to see others in this light, then there is no one that we cannot speak with, and we are able to learn from everyone.

Conversation, at its finest, is no small matter. It is a chance to touch the soul of another and expand our own. Put differently, we can forge a profound human connection with a perfect stranger because, ultimately, there are no strangers. We might think of others as the missing pieces of our puzzle—the more we know them, the more we know ourselves (and vice versa). Approaching another with openness, detachment, empathy and humility, we stand to discover something new about the world or ourselves. If we maintain curiosity and reverence for our conversational partner, while remaining willing to be surprised, we might emerge from our talk with them improved, perhaps, transformed.

A hearty talk is also an opportunity to practice radical honesty. If we are not willing to lay our heart bare, and give of ourselves meaningfully, why should they? It’s the first person on the dance floor, willing to make a fool of themselves, that gets the party started. To be that person requires taking a risk and courage, as all-important human interaction does. Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, Heraclitus, puts it this way: “Man is most nearly himself when he achieves the seriousness of a child at play.” That’s what conversation is: serious play.

In a sense, all of life is conversation, really—with ourselves, others, this world and the Next. In conversation, as in real life, violence is a failure of imagination and an admission of defeat. Polite provocation can spark a healthy debate, where we are challenged and challenging. But, if a passionate, spirited, enthusiastic discussion devolves into one that is angry, vicious, or condescending, all the latent good of the exchange is lost. Good talk is an art, like dance, where we take turns leading and come back together. It is also a sport, but not a competitive one with winners and losers, rather one where the shared goal is to keep the ball up in the air.

Paradoxically, good conversation must also respect silence. The same way having something to say comes from quiet contemplation, and writing is born of reading, so non-verbal exchange in a conversation is as significant, if not more, than what is actually being said. Try not to rush the silences, yours or another’s, out of nervousness, fear or awkwardness. Give time for what is said to sink in and be processed. It’s a rare privilege to be allowed to think, wordlessly, in the presence of another and an act of trust.

Ultimately, conversation is a living thing, and nothing alive can be calculated or anticipated. There are no hard and fast rules for social intercourse that cannot be broken or rewritten. But, if we keep these basic guidelines, loosely, in mind next time we interact with a fellow human being in real-time, we might be rewarded with a conversation that is revelatory, entertaining, civilizing.

Photograph: Public Domain

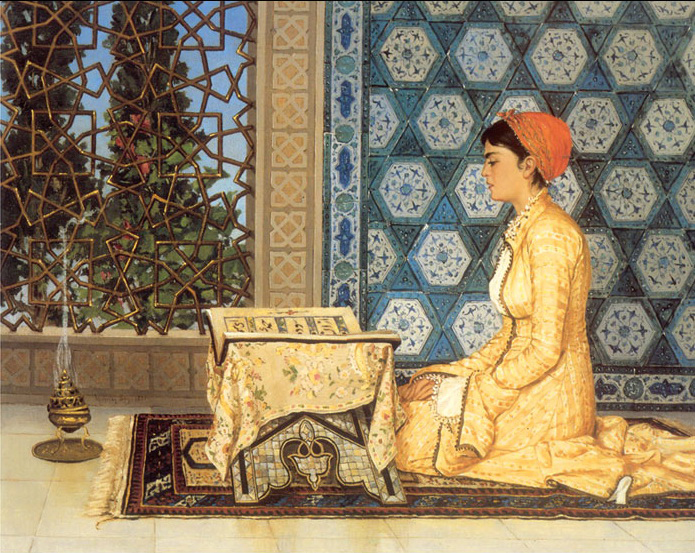

Reverence for the Visible and Invisible Worlds

“This visible world is a trace of that invisible one

and the former follows the latter like a shadow.”

—Al Ghazali

Lately, I’m consumed with the idea of the artist as mystic, and the appreciation of beauty as a form of prayer. Following a dream contributing to his conviction of having been “called”, philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote in a letter at the age of 31: “I had a task … to become a star in the sky.” In his conception of philosophy—as a means of authentic existence equally concerned with logic as ethics—the spiritual, artistic, and metaphysical aspects of a calling are nearly fused.

At a feverish pitch, we see this ascetic philosopher flirting with poverty, giving away an immense family fortune to pursue his ideal of living and working with the rural poor; with solitude, spending years alone in Norway and Ireland, to meditate and write; and with death, in the trenches of World War I, in the belief that he did not deserve to live unless he created great work.

The artistic-philosophic landscape is teeming with seers of this type. The power and aura of these fiery spirits derive as much from the truths or realities they have revealed as what they’ve had to sacrifice along the way; it is an authority born of the tension between what is accomplished and what is suffered.

On a personal note, I observe that something is taking place within me, a shift as decisive and imperceptible as a continental drift. I, who once identified with my mind, have come to feel I am standing at the very edge of it, and that it’s thin and flat. The time came to leap. My way into the life of the spirit began, unwittingly, when I first began experimenting with silence in university. I would attempt to go on silent fasts for days, rationing words, and speaking only when I must—perhaps a mouthful in class, or even less if someone absolutely needed to hear from me. Otherwise, friends understood that I’d “gone under” and only the very committed continued leaving me voice messages or, braver still, tagging along, noiselessly.

The idea at the time—more inner imperative, really, than any sort of formulated thought—was to sound my depths and think things through. This was my first taste of freedom as an adult, and that was how I chose to exercise it. It was as though, suddenly and without explanation, I was taken in for questioning, and I had to play both parts: officer and suspect. Who was I? What did I know? Why am I here? Do I have an alibi?

Typically, I’d walk around all day in a semi-trance talking back to the books I’d read, lost in the echo chamber of my head. I read a great deal more those days, again out of an inner imperative, but hardly the assigned work. My self-imposed reading list was a volatile cocktail, unequal parts literature and philosophy, and the discovery of those great contrarians, Wilde and Nietzsche, made my world spin faster.

Unaware of it then, this obsessive reading was in fact teaching me how to write. The rhythms and cadences of my literary and philosophical masters insinuated themselves into my style, just as their stances and daring were persuading me to distrust ready-made ideas and try to formulate better questions.

It was out of these silences and (attendant) solitude that I began writing what would become a book of aphorisms—by transcribing the heady conversations that I was having with myself at the time. My “method” in writing these aphorisms was simply to jot down on a scrap of paper (the back of a napkin, receipt, or whatever else was handy) what I thought was worth quoting from my soul’s dialogue with itself. If ever I tried keeping a notebook, the thoughts would hesitate leaving their cave, sensing ambush. So, by night I kept bits of paper and a pencil by my side, just in case. And, when something did occur to me, I feverishly scribbled it down in the dark, without my glasses, out of the same superstitious cautiousness of scaring ideas off.

These aphorisms were to reveal me to myself and served as the biography of my mental, spiritual, and emotional life. I read as I wrote, helplessly, in a state of emergency; in my youthful fanaticism, I was convinced I was squeezing existence for answers, no less. I felt that one should only read on a need-to-know basis, and write discriminatingly, with the sole purpose of intensifying consciousness.

Strangely, during these years of white-hot inspiration, I discovered that when I returned home to Egypt (for the summer, Christmas, and eventually following graduation) I was unable to write aphorisms. No longer the master of my environment, and forced to accommodate the interruptions that make a life, I gradually realized that because I had lost my silences, I had lost my voice. Which is to say, I composed the bulk of the aphorisms in my book, Signposts to Elsewhere, before I turned twenty-two.

It would take me several years to begin writing again and, out of this unsettling and involuntary silence, would be born two new forms: poetry and eventually essays. After a decade or so of aphoristic silence, spurred by the terse wisdom of the Tao Te Ching and Sufi teachers, I find myself returning to these brief arts and speaking to myself in sayings, once more, noting how I and the writing are changing.

Photograph: Public Domain

What the Migraine Said

These are the wincing days: walking around shading eyes with hands, ice-pack atop head and, vampire-like, avoiding light, seeking quiet and dark spaces. For weeks—nearly a month —I’ve been experiencing a fairly persistent migraine. It subsides just long enough for me to read or write a little but makes itself known if I stare overlong at The Screens, big or small (television, computer and iPhone). This has limited my concentration and has me staggering around in a kind of haze during waking hours.

Alarmed by its persistence, I visited the emergency room, where I spent twelve hours (from 7 pm–7 am) between waiting to be seen and being seen. Mercifully, CAT scan and blood work came back clean. I feel bad complaining, in comparison to the major tragedies I witnessed in the waiting room: relatives howling in pain, writhing on the ground, having just learned of the death of their loved ones, domestic abuse, shootings, all variety of life’s walking wounded.

I’ve been taking medication to control the pain, and gotten an eye exam since, but still feel out of it, dizzy and nauseous even as I type this, versus the acute pain I felt weeks earlier. If the new glasses/prescription don’t help, I’m meant to visit a neurologist, next. This experience served as inspiration for the poem, below.

What the Migraine Said

As I lie, here, half in and out of consciousness

I imagine my migraine as a world migraine

my cluster headache as a cluster of world aches

that we must tip toe around like a sleeping tigerThe sleep of reason produces monsters—

this we know from art and the news:

murder and sham leaders shooting themselves

in one foot and chewing on the other.But, the sleep of reason produces angels, also

like Love, which is no whimsical thing,

a love like bull, bullfighter and bloody cape,

billowing in the wind, like an open heartBeckett said this best, truth in paradox:

The mystics … I like … their burning illogicality

— the flame … Which consumes all our filthy logic …

Where there are demons there is something preciousOnce we know this, the rest is silence.

The master is not permitted

the same mistakes of a novice.

Photograph: Public Domain

Encounter

I stirred in the small hours of the morning. Sensing a presence, I did not return to sleep, but ventured into the living room, apprehensively. There, by the balcony, sat a familiar figure—cross-legged and reading in the semi-dark, with just the milky moonlight for company.

I do not know how I knew, but I did. I recognized the intruder, at once, with a mixture of dread and affection. “I’m sorry,” were the only words to leave my lips. “I’m sorry, too,” replied my longed-for self, with a sigh of infinite kindness and pity.

He did not rise to greet me and, somehow, spoke without words, transmitting what was needed. Catching his glistening eye, the caring made me cry. “You’ve taken every detour to avoid me,” he gently reproached. “For every step I’ve taken towards you, you’ve taken back two.”

I did not know what to say in my defence (how could I protest against myself?). “I missed you,” he said, “and feared you’d forgotten me.” His admonishment was tender as a kiss. “I visit from time to time, and hope you’ll ask me to stay.” I knew what he said was true, and felt that way, too.

“I worried,” he continued, “if I postponed this visit, we might never meet, in this life … and so I came to sharpen your appetite.” He rose and moved towards me. “There’s no need to speak, return to sleep. But when you rise, try to remember me. And to keep awake.”

Post Notes

- Yahia Lababidi’s Daily Aphorism Wisdom Texts

- Yahia Lababidi on Poets & Writers

- Yahia Lababidi on Twitter

- Yahia Lababidi: What Remains to be Said

- Daniel Ladinsky & Marwa Adel: Rumi

- Irina Tweedie: The Daughter of Fire

- Philip Jacobs: Dance of the Dervishes

- Fakhruddin ‘Araqi: Divine Flashes

- Kahlil Gibran: Poet, Painter, Prophet

- Hafiz: The Gift