Image: Public Domain

A creed to the creative life

“Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.”

READING THE WORDS of Wassily Kandinsky’s elegant masterpiece, for there is no other term to describe it, renders a poetic frisson deep within me such as I have rarely experienced before simply through the power of prose, despite the text being a translation from its original German.

Indeed, akin to Andrei Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time—a homage to the divine in cinematography—Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Über das Geistige in der Kunst, 1912) is a metaphysical tract beyond compare in the history of the visual arts.

Image: Public Domain

“The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural …

The brighter it becomes, the more it loses its sound, until it turns into silent stillness and becomes white.”

Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky (16th December 1866–13th December 1944) was a Russian abstract painter and art theorist. Born in Moscow, he lived in Germany and taught at the Bauhaus School of Art and Architecture, later installing himself in an apartment in Paris, where he would live for the rest of his life.

A sensitive and reflective child, Kandinsky was fascinated by the fanfare of sensory experience that childhood affords, through colour and sound and music, revelling in playing both the piano and cello. When he was in his early teens, he saved up enough money to buy his first box of oil paints.

In 1895, an exhibition in Moscow showcasing the work of the French Impressionists would irrevocably seal his fate when his eyes fell upon Claude Monet’s Haystacks:

That it was a haystack the catalogue informed me. I could not recognize it. This non-recognition was painful to me. I considered that the painter had no right to paint indistinctly. I duly felt that the object of the painting was missing. And I noticed with surprise and confusion that the picture not only gripped me but impressed itself ineradicably on my memory. Painting took on a fairy-tale power and splendour.

Music was similarly becoming subject to transformative forces. It was around this period that Kandinsky encountered Richard Wagner’s opera, Lohengrin, wherein music and melody appear to transcend more conventional limitations of lyricism and which would have a revelatory effect upon the young man.

Combined with his concurrent interest in the theosophical work of Madame Blavatsky, with her emphasis on the creative imagination and geometrical symbolism in relation to the nature of divinity, the canvas was primed for Kandinsky’s ineluctable metamorphosis.

Image: Public Domain

“A painter, who finds no satisfaction in mere representation, however artistic, in his longing to express his inner life, cannot but envy the ease with which music, the most non-material of the arts today, achieves this end. He naturally seeks to apply the methods of music to his own art.”

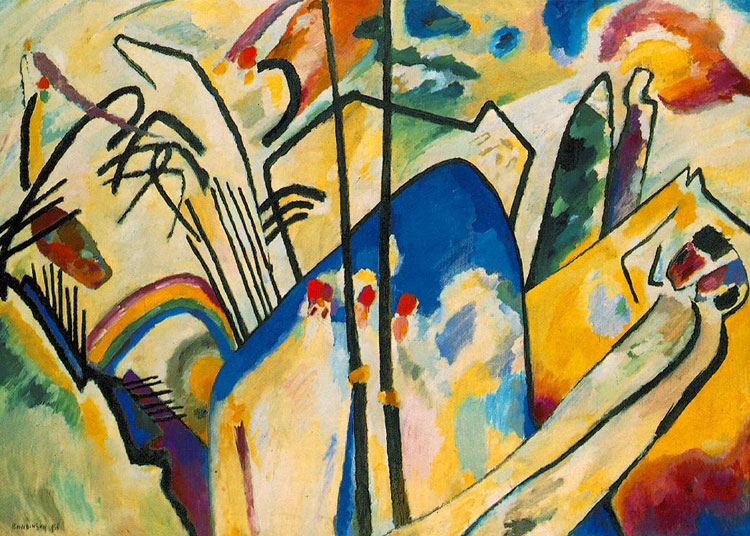

And thus, from this moment forward, Kandinsky’s life would be driven by the pursuit of creativity that no longer concentrated on the pictorial representation of the objective world but instead sought to symbolize the innerer Klang or “inner need” of the artist, harkening towards spiritual awakening and transcendence through the medium of art.

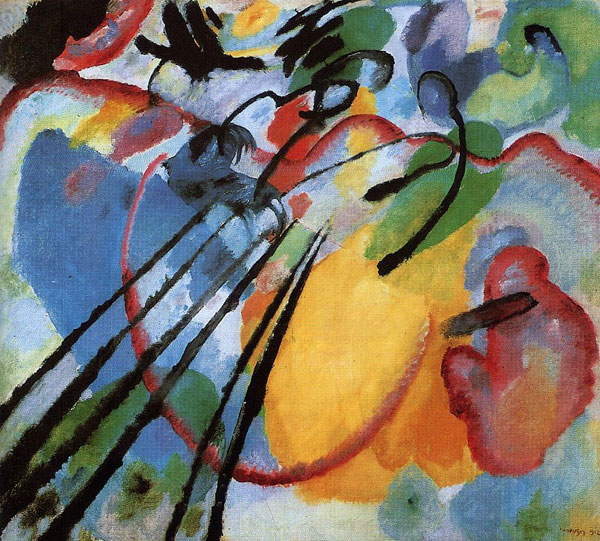

Moreover, always fascinated by the synæsthesic relationship between music and painting, Kandinsky longed to imbue his canvases with the abstract melodic language of the universal sensations of the inner soul. His symphonic configurations, therefore, were categorized into three distinct types of illustration: “impressions”, “improvisations” and “compositions”.

Whilst impressions were predominantly inspired by external reality, improvisations and more developed compositions were birthed by unconscious, spontaneous expressions stimulated by inner feelings and subjective experience. In other words, Kandinsky’s creed for creativity was the very embodiment of what French philosopher, Michel Henry, defines as the “Phenomenological Life”.

As the translator, Michael T. H. Sadler, also makes clear in his introduction:

Kandinsky is painting music. That is to say, he has broken down the barrier between music and painting, and has isolated the pure emotion which, for want of a better name, we call the artistic emotion. Anyone who has listened to good music with any enjoyment will admit to an unmistakable but quite indefinable thrill. He will not be able, with sincerity, to say that such a passage gave him such visual impressions, or such a harmony roused in him such emotions. The effect of music is too subtle for words.

Image: Public Domain

“Our epoch is a time of tragic collision between matter and spirit and of the downfall of the purely material world view.”

Despite writing more than a century ago, Kandinsky’s message couldn’t be more prophetic for our modern age, an era beguiled by consumerist culture and lost in a spiralling descent into a simulacrumian abyss:

This all-important spark of inner life today is at present only a spark. Our minds, which are even now only just awakening after years of materialism, are infected with the despair of unbelief, of lack of purpose and ideal. The nightmare of materialism, which has turned the life of the universe into an evil, useless game, is not yet past; it holds the awakened soul still in its grip. Only a feeble light glimmers like a tiny star in a vast gulf of darkness …

Indeed, Kandinsky laments the utter inability of the decadent bourgeoisie to truly value the raison d’être of a visual work of art:

The spectator is too ready to look for meaning in a picture—i.e., some outward connection between its various parts. Our materialistic age has produced a type of spectator or ‘connoisseur’, who is not content to put himself opposite a picture and let it say its own message. Instead of allowing the inner value of the picture to work, he worries himself in looking for ‘closeness to nature’ or ‘temperament’ or ‘handling’ or ‘tonality’ or ‘perspective’ or what not. His eye does not probe the outer expression to arrive at the inner meaning.

In a conversation with an interesting person, we endeavour to get to his fundamental ideas and feelings. We do not bother about the words he uses, nor the spelling of those words, nor the breath necessary for speaking them, not the movements of his tongue and lips, not the psychological working on our brain, not the physical sound in our ear, nor the psychological effect on our nerves.

We realize that these things, though interesting and important, are not the main things of the moment, but that the meaning and idea is what concerns us. We should have the same feeling when confronted by a work of art. When this becomes general the artists will be able to dispense with natural form and colour and speak in purely artistic language.

Image: Public Domain

“Everything starts from a dot.”

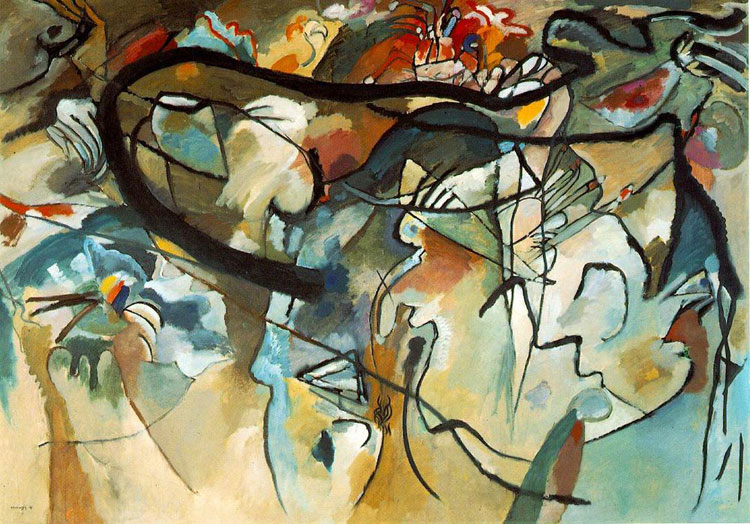

In what has become one of the most famous visual metaphors for exemplifying the spiritual life, Kandinsky compares the inner artistic tension, whilst drawing on the philosophical tenets of Blavatsky’s theosophy, to that of a geometrical object:

The life of the spirit may be fairly represented in diagram as a large acute-angled triangle divided horizontally into unequal parts with the narrowest segment uppermost. The lower the segment the greater it is in breadth, depth and area.

The whole triangle is moving slowly, almost invisibly forwards and upwards. Where the apex was today, the second segment is tomorrow; what today can be understood only by the apex and to the rest of the triangle as an incomprehensible gibberish, forms tomorrow the true thought and feeling of the second segment.

At the apex of the top segment stands often one man, and only one. His joyful vision cloaks a vast sorrow. Even those who are nearest to him in sympathy do not understand him. Angrily they abuse him as charlatan or madman. So in his lifetime stood Beethoven, solitary and insulted.

How many years will it be before a greater segment of the triangle reaches the spot where we once stood alone? Despite memorials and statues, are there really many who have risen to his level?

In every segment of the triangle are artists. Each one of them who can see beyond the limits of his segment is a prophet to those about him and helps the advance of the obstinate whole. But those who are blind or those who retard the movement of the triangle for baser reasons, are fully understood by their fellows and acclaimed for their genius […]

Every segment hungers consciously or, much more often, unconsciously for their corresponding spiritual food. This food is offered by the artists, and for this food the segment immediately below will tomorrow be stretching out eager hands.

Image: Public Domain

“Lend your ears to music, open your eyes to painting, and … stop thinking! Just ask yourself whether the work has enabled you to ‘walk about’ into a hitherto unknown world. If the answer is yes, what more do you want?”

Furthermore, Kandinsky again alerts us to the lonely and alienated path of the artist, chosen in spite of herself to fulfil a destiny and a calling serving a higher cause, amidst the degeneracy of contemporary life:

The solitary visionaries are despised or regarded as abnormal and eccentric. Those who are not wrapped in lethargy and who feel vague longings for spiritual life and knowledge and progress, cry in harsh chorus, without any to comfort them. The night of the spirit falls more and more darkly. Deeper becomes the misery of these blind and terrified guides and their followers, tormented and unnerved by fear and doubt, [who] prefer to this gradual darkening the final sudden leap into the blackness.

At such a time art ministers to lower needs and is used for material ends. She seeks her substance in hard realities because she knows of nothing nobler. Objects, the reproduction of which is considered her sole aim, remain monotonously the same. The question ‘what?’ disappears from art; only the question ‘how?’ remains […] Art has lost her soul. In the search for method the artist goes still further. Art becomes so specialized as to be comprehensible only to artists and they complain bitterly of public indifference to their work.

For since the artist in such times has no need to say much but only to be notorious for some small originality and consequently lauded by a small group of patrons and connoisseurs (which incidentally is also a very profitable business for him), there arises a crowd of gifted and skilful painters, so easy does the conquest of art appear. In each artistic circle are thousands of such artists, of whom the majority seek only for some new technical manner and who produce millions of works of art without enthusiasm, with cold hearts and souls asleep.

Competition arises. The wild battle for success becomes more and more material. Small groups who have fought their way to the top of the chaotic world of art and picture-making entrench themselves in the territory they have won. The public, left far behind, looks on bewildered, loses interest and turns away.

Image: Public Domain

“Colour is a power which directly influences the soul.”

But despite all this confusion, this chaos, this wild hunt for notoriety, the spiritual triangle, slowly but surely, with irresistible strength, moves onwards and upwards […]

First by the artist is heard his voice, the voice that is inaudible to the crowd. Almost unknowingly the artist follows the call. Already in that very question ‘how?’ lies a hidden seed of renaissance. For when this ‘how?’ remains without any fruitful answer, there is always a possibility that the same ‘something’ (which we call personality today) may be able to see in the objects about it not only what is purely material but also something less solid; something less ‘bodily’ than was seen in the period of realism, when the universal aim was to reproduce anything ‘as it really is’ and without fantastic imagination.

If the emotional power of the artist can overwhelm the ‘how?’ and can give free scope to his finer feelings, then art is on the crest of the road by which she will not fail later on to find the ‘what’ she has lost, the ‘what’ which will show the way to the spiritual food of the newly awakened spiritual life. This ‘what?’ will no longer be the material, objective ‘what’ of the former period, but the internal truth of art, the soul without which the body (i.e. the ‘how’) can never be healthy, whether in an individual or in a whole people.

Image: Public Domain

“To create a work of art is to create the world.”

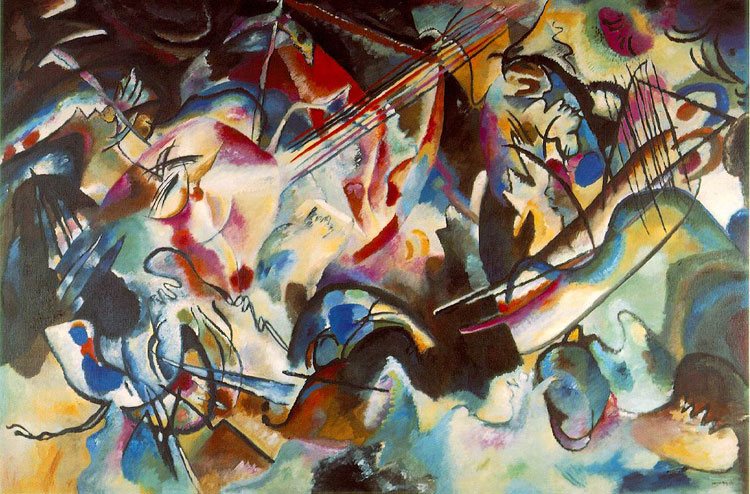

And Kandinsky doesn’t stop there. Writing during a time of increasing nihilistic dread and existential anxiety under the encroaching shadow of imminent world war and global apocalypse, he develops further his theories in a later chapter entitled “The Pyramid”, evoking the great philosophers of the past in a reverential homily to the artist as prophet and his redemptive power to transform the very future of mankind:

And so at different points along the road are the different arts, saying what they are best able to say and in the language which is peculiarly their own. Despite, or perhaps thanks to, the differences between them, there has never been a time when the arts approached each other more nearly than they do today, in this later stage of spiritual development.

In each manifestation is the seed of a striving towards the abstract, the non-material. Consciously or unconsciously they are obeying Socrates’ command—Know Thyself. Consciously or unconsciously artists are studying and proving their material, setting in the balance the spiritual value of those elements, with which it is their several privilege to work.

And the natural result of this striving is that the various arts are drawing together. They are finding in music the best teacher. With few exceptions music has been for some centuries the art which has devoted itself not to the reproduction of natural phenomenon but rather to the expression of the artist’s soul, in musical sound.

Image: Public Domain

“Each colour lives by its mysterious life.”

A painter, who finds no satisfaction in mere representation, however artistic, in his longing to express his inner life, cannot but envy the ease with which music, the most non-material of the arts today, achieves this end. He naturally seeks to apply the methods of music to his own art. And from this results that modern desire for rhythm of music in painting, for mathematical, abstract construction, for repeated notes of colour, for setting colour in motion.

This borrowing of method by one art from another can only be truly successful when the application of the borrowed methods is not superficial but fundamental. One art must learn first how another uses its methods, so that the methods may afterwards be applied to the borrower’s art from the beginning and suitably. The artist must not forget that in him lies the power of true application of every method but that that power must be developed.

In manipulation of form music can achieve results, which are beyond the reach of painting. On the other hand, painting is ahead of music in several particulars. Music, for example, has at its disposal duration of time; while painting can present to the spectator the whole current of its message at one moment. Music, which is outwardly unfettered by nature, needs no definite form for its expression. Painting today is almost exclusively concerned with the reproduction of natural forms and phenomena. Her business is now to test her strength and methods, to know herself as music has done for a long time and then to use her powers to a truly artistic end.

And so the arts are encroaching one upon the other and from a proper use of this encroachment will rise the art that is truly monumental. Every man who steeps himself in the spiritual possibilities of his art is a valuable helper in the building of the spiritual pyramid, which will some day reach to heaven.

Image: Public Domain

“The artist must have something to say, for mastery over form is not his goal but rather of form to its inner meaning.”

So often testaments to artistic theory are full of abstractions and platitudes, making any meaningful sense only to their creators and cliques of loyal followers and fans; by expressing a universally divine symbolism, however, Kandinsky’s credo to the artistic life is able to reach well beyond the coterie of visual media embracing all the creative arts—indeed deep into the consciousness of society and life itself:

When science, religion and morality are shaken, the two last by the strong hand of Nietzsche, and when the outer supports threaten to fall, man turns his gaze from externals on to himself. Literature, music and art are the first most sensitive spheres in which this spiritual revolution makes itself felt. They reflect the dark picture of the present time and show the importance of what at first was only a little point of light noticed by few and for the great majority non-existent. Perhaps they even grow in their turn but on the other hand they turn away from the soulless life of the present towards those substances and ideas which give free scope to the non-material strivings of the soul […]

The work of art is born of the artist in a mysterious and secret way. From him it gains life and being. Nor is its existence casual and inconsequent but it has a definite and purposeful strength, alike in its material and spiritual life. It exists and has power to create spiritual atmosphere; and from this inner standpoint one judges whether it is a good work of art or a bad one. If its ‘form’ is bad it means that the form is too feeble in meaning to call forth corresponding vibrations of the soul […] The artist is not only justified in using but it is his duty to use only those forms which fulfil his own need […] Such spiritual freedom is as necessary in art as it is in life.

Image: Public Domain

“Of all the arts, abstract painting is the most difficult. It demands that you know how to draw well, that you have a heightened sensitivity for composition and for colours, and that you be a true poet. This last is essential.”

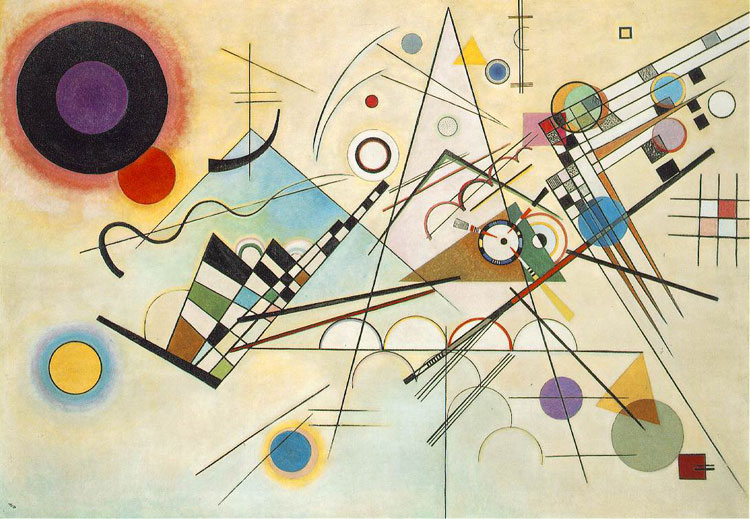

As a pioneer of abstract modern art, Wassily Kandinsky practised exactly what he preached. His rapturous and tumultuous artwork exemplifies his fundamental belief that painting can embody all the subjective feelings and emotions inherent in the non-material musicality of sound, evoking aesthetic and spiritual experience deep in the hearts and minds of his fellow man.

Moreover, in his quest to express the timeless and transcendental through the language of form and colour, Kandinsky repeatedly reiterates how this “inner need” of the artist becomes a great responsibility in the soul’s pilgrimage to all that is beautiful, ineffable and profound:

Painting is an art and art is not vague production, transitory and isolated, but a power which must be directed to the improvement and refinement of the human soul—to, in fact, the raising of the spiritual triangle.

If art refrains from doing this work, a chasm remains unbridged, for no other power can take the place of art in this activity. And at times when the human soul is gaining greater strength, art will also grow in power, for the two are inextricably connected and complementary one to the other. Conversely, at those times when the soul tends to be choked by material disbelief, art becomes purposeless and talk is heard that art exists for art’s sake alone. Then is the bond between art and soul, as it were, drugged into unconsciousness. The artist and spectator drift apart, till finally the latter tuns his back on the former or regards him as a juggler whose skill and dexterity are worthy of applause.

It is very important for the artist to gauge his position aright, to realize that he has a duty to his art and to himself, that he is not king of the castle but rather a servant of a nobler purpose. He must search deeply into his own soul, develop and tend it, so that his art has something to clothe and does not remain a glove without a hand […]

The artist is not born to a life of pleasure. He must not live idea; he has a hard work to perform and one which often proves a cross to be borne. He must realize that his every deed, feeling and thought are raw but sure material from which his work is to arise, that he is free in art but not in life […]

If the artist be priest of beauty, nevertheless this beauty is to be sought only according to the principle of the inner need and can be measured only according to the size and intensity of that need. That is beautiful which is produced by the inner need, which springs from the soul.

Post Notes

- WassilyKandinsky.net

- Paul Cézanne: La Montagne Sainte-Victoire

- Ansel Adams: The Search for Beauty

- Antony Gormley: Sculpted Space Within and Without

- Eric Nicholson: William Blake’s Vision of the Book of Job

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Josef Pieper: Only the Lover Sings

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Mark Rothko: The Artist’s Reality

- Rupert Spira: A Meditation on I Am