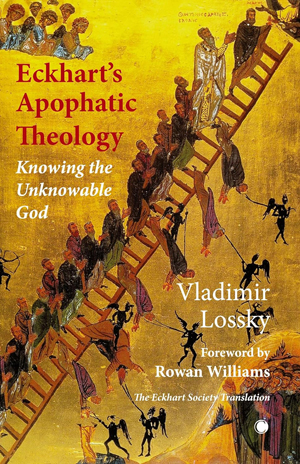

Knowing the unknowable God

The rarest merit of this lengthy study resides precisely in its refusal to reduce Eckhart’s theology to the systematic development of one core idea. However, neither is this theology conceived of as a form of eclecticism in which each core idea would have its place and would have its own turn to be uppermost. If there is one single notion in Eckhart’s theology which could be said to be foundational, then it would be God or, more exactly, the notion of God as ineffable. The title of this book itself pinpoints the very heart of the doctrine, but Eckhart himself conceived of his work as an eminently positive enquiry into our unknowing of the divinity. Trying out, in succession, all the paths already known, and pushing right to the end the implications of each one, Eckhart induces one to see that all one can rightly affirm with respect to God can, and indeed must, itself ultimately be denied in order to make room for an apparently contradictory affirmation.

—Étienne Gilson, Member of the Académie Française,

Preface to the First Edition,

Vladimir Lossky, Eckhart’s Apophatic Theology

WITH THE RISE of monist metaphysics in recent decades, the name of Eckhart von Hochheim, (c. 1260–c. 1328), the German theologian, philosopher and mystic, more commonly known as Meister Eckhart, will be all too familiar to those interested in a serious-minded exploration of the meaning of life.

Despite being tried as a heretic, he was one of the most learned and beloved teachers of the mediaeval period during a critical time in the evolution of European thinking, having documented the Neoplatonic concept of “oneness” or “esse” or “divine ineffability”—the idea that the ultimate principle of the universe is a single and undivided whole.

In modern times, Meister Eckhart’s message has forged a syncretic link between Western nondualism and Eastern mysticism. Indeed, his startling prose exhibits many esoteric parallels specifically with Buddhist and Vedic literature, which utilize the path of negation or via negativa or “apophaticism” as the path to God.

The refusal to find the name to properly designate a God who cannot be known without a margin of ignorance intervening in the knowledge itself is common to all theognoses [theological gnoses] that accept apophaticism, whether to immediately overcome it [i.e., ‘apophaticism’] in a theological epistemology or to make it the path to a ‘beyond all knowledge’. However, while an ‘ineffable’ God would seem to exist as a common ground between those who have, to varying degrees, reserved a space for the ‘way of negations’ in their religious thought, one could also say that there are, in fact, as many ‘ineffabilities’ as there are negative theologies. Truly, Plotinus’ ineffable is not the same as Pseudo-Dionysius’, which, in its own right, is quite different from the ineffable of St Augustine. Here again, of course, we must distinguish St Augustine’s ineffable from that of St Thomas Aquinas. Rather, it would seem that it is the concept that a theologian creates out of the ineffability of God that determines the role which the apophatic moment will play in his thinking. It is for this reason that we wished to begin our study of the idea of God in the works of Meister Eckhart, and, in particular, of is negative theology, with the topic of the search for the ineffable.

This search involves a region which entails negation. What, then, is a negative path, if not a search in which one is obliged successively to reject all that can be found and named, finally even requiring the denial of the search itself, since the entire concept of searching implies an idea of that which is sought after?

—Vladimir Lossky, Eckhart’s Apophatic Theology

Vladimir Lossky (1903–7th February 1958) was an influential Eastern Orthodox theologian, who was born in Germany, grew up in St Petersburg but spent most of his adult life in exile in Paris, like many other non-Marxist intellectuals, where he taught dogmatic theology at the St Dionysus Institute in Paris and the Orthodox Institute of St Irene. Among his best-known works is The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church.

The manuscript for Eckhart’s Apophatic Theology actually started life as a doctoral thesis in the humanities, which Lossky was due to submit to the Sorbonne upon its completion; however, he quite literally died in the course of its research at the relatively young age of 55, leaving his friend and mentor Maurice de Gandillac and a younger friend and disciple Olivier Clément to collate and transcribe the final pages, as well as painstakingly compile a comprehensive index.

Originally composed and published in French as Théologie Négative et Connaissance de Dieu chez Maître Eckhart in 1960, this formidable posthumous text has been elegantly and accurately translated for the first time into English by two trustees of the Eckhart Society—Monk Sophrony and Dr Jonathan Sutton—who have done a first-class job in turning dense abstractions into a readable narrative, which has been warmly acclaimed as a masterpiece of interpretative scholarship.

In this perspective, not only does the kind of apophaticism which is directed towards the ineffability of the esse absconditum [hidden being] give way to the negation of the modus significandi [pedanticism] in the names attributed to God, but also the mystical intuition of a realm that is closed and decisively inaccessible, pertaining to the Being which is beyond all causality, retreats, though without totally disappearing, before a vision which is separated from Cause and effects. We have seen […] that the mystical conception of the esse absconditum indistinctly includes the three following moments: (1) the esse which is God; (2) the esse as a divine operation in the intimate depths of the soul; and (3) the perfect esse which creatures have in God. These three moments represent but one single ineffable reality when Eckhart wishes to speak of the esse on the supreme plane, that of mystical experience. Their unity remains unbroken even when being, considered as a ‘work’ that is simultaneously begun and accomplished by God, appears under the dynamic aspect of a circular movement: descent, in which the operation of God becomes obscured by created nature, and ascent towards the ‘clarity’ of being that is ‘pure of all addition’, at the origin of all esse.

—Vladimir Lossky, Eckhart’s Apophatic Theology

Framed by six key statements about God’s essence—(1) Nomen Innominabile [Name Unnamable]; (2) Nomen Omninominabile [The Omnipresent Name]; (3) Ego Sum Qui Sum [I Am Who I Am]; (4) Regio Dissimilitudinis Infinitae [A Region of Infinite Dissimilarity]; (5) Splendor in Medio [Middle Splendour]; (6) Imago in Speculo [Image in the Mirror]—Eckhart’s Apophatic Theology is the culmination of a long and exacting process, whereby Lossky embraces the ways of thinking of a 13th-century German monk and mystic.

While refusing to simplify Eckhart’s theology to a system or single motif, Lossky explores in detail the various ramifications of Eckhart’s insistence on the ineffability of God. Is God to be regarded as “being”, or the “One” or “Intellect”? Does God’s pure expression of each of these preclude the others? Presenting Eckhart’s approach to this dilemma and guided by careful engagement with a multitude of sources, this erudite work is both meticulous and exhaustive.

Indeed, during a time period flooded with flaky self-help books and pop psychology, it is reassuring to know that there is still the demand for serious and thoughtful literature expounding the very essence of life. Beautifully produced by James Clarke & Co., with a foreword by Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, academics and scholars will welcome this eagerly anticipated rendition.

‘To be’ is to remain absolutely identical with oneself, to subsist exclusively an an essence, without this exclusivity (or ‘purity’) receiving a negative character; truly, that would then limit ‘that which one is’ by opposing it to ‘that which one is not’. A being which distinguishes itself from others in what it is, necessarily will be enclosed within a moment of negativity and non-identity, which is to say, of non-being. Its identity is but relative, this ‘being oneself’ presupposes a series of negations of identity, a multitude of negative determinations with reference to all that is ‘other’. Such a being has no identity exclusive to itself, for this notion of ‘oneself’ includes in its positive definition all the negative relationships with that which it is not. To be exclusively oneself, without any dependence upon alterity of any kind at all, it would be necessary for the identity of ‘that which is’ to be capable of being negatively expressed as an exclusion of all negativity. Thus, the unum negative dictum [one thing said negatively], the negatio negationis esse [the negation of the negative being], is, as we have seen, the most pure affirmation, the absolute positivity of the Being-who-is-Being; Ego sum qui sum [I am who I am].

—Vladimir Lossky, Eckhart’s Apophatic Theology

Post Notes

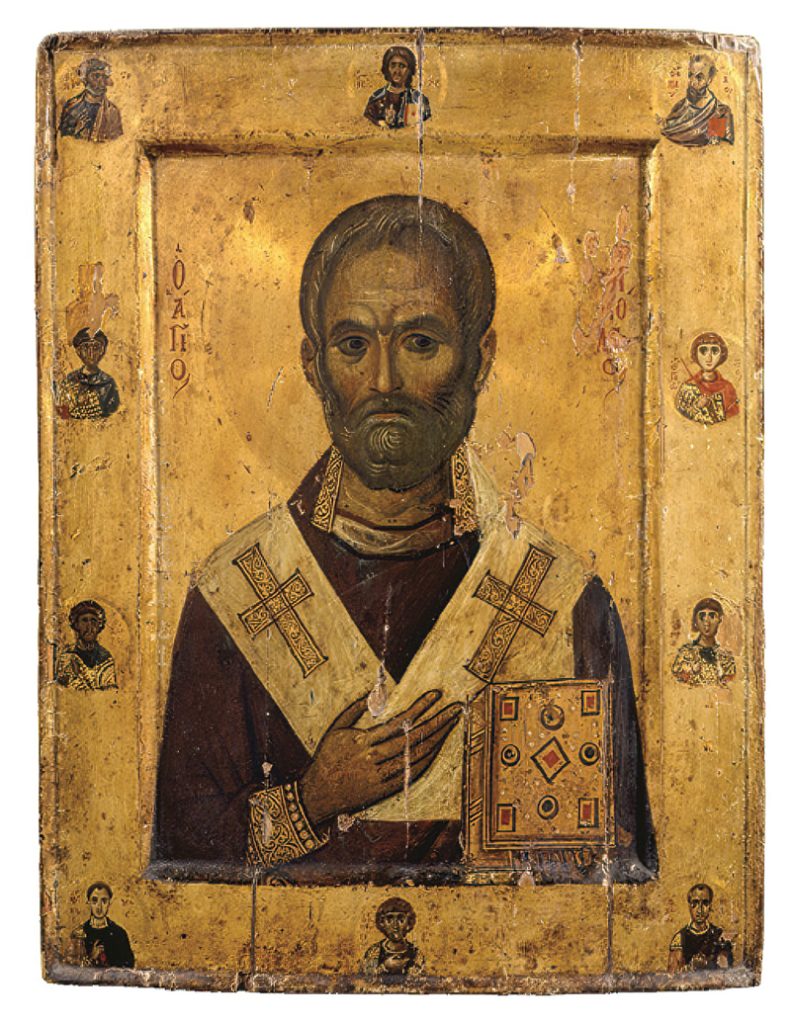

- Feature image: Saint Catherine, the Mother of God of the Bush, and Prophet Moses, [detail],

© St. Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai - James Clarke & Co.

- The Eckhart Society

- St. Catherine’s Monastery at God-trodden Mount Sinai

- Dag Hammarskjöld: Markings

- Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Teresa of Ávila: The Ecstasy of Love

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Michael Molinos: The Spiritual Guide

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme