Experience Monk’s House through the words of Virginia Woolf with the National Trust

Monastic retreat

“It is much more important to be oneself than anything else.”

―Virginia Woolf, “A Room of One’s Own”

WHAT TO DO when the artistic muse slams the front door and struts off down the garden path to disappear along the country lane seemingly forever? Take inspiration from a female writer who understood the mental anguish of generating meaningful literature and yet, through introspection and unflinching perseverance, produced some of the most exquisitely profound prose in the entire English language.

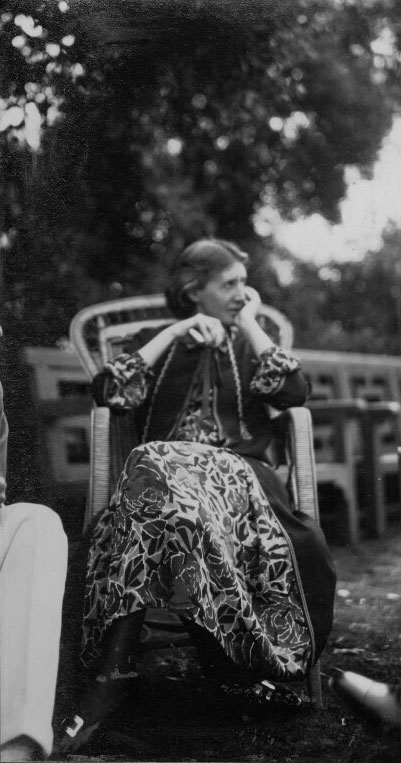

It is the last day of the year that Monk’s House, the country retreat of Leonard and Virginia Woolf (25th January 1882–28th March 1941), is open to the public. Installed in the hamlet of Rodmell amidst the undulating hills of the South Downs, I arrive in the hopes of restoring a love of the creative act.

Vintage Snapshot Print, June 1926

NPG x144307

Image: [CC BY-NC-ND 3.0]

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The spirit of peace descended like a cloud from heaven, for if the spirit of peace dwells anywhere, it is in the courts and quadrangles of Oxbridge on a fine October morning. Strolling through those colleges past those ancient halls the roughness of the present seemed smoothed away; the body seemed contained in a miraculous glass cabinet through which no sound could penetrate, and the mind, freed from any contact with facts (unless one trespassed on the turf again), was at liberty to settle down upon whatever meditation was in harmony with the moment.

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Serendipitously, it is a similarly fine October morning and the beauty of the walled garden that presents itself as I round the corner could rival any Oxbridge college. Descending brick steps through the conservatory into an unassuming clapboard cottage, the words of Virginia Woolf float into my mind: “There is little ceremony or precision at Monk’s House. It is an unpretending house, long & low, a house of many doors.”

Indeed, the chartreuse-green sitting room is unpretentiously adorned with the paintings, textiles and pottery of Vanessa Bell, Virginia’s sister, and fellow painter, Duncan Grant, together with furniture in the style of the Omega Workshops, a collective of artists founded by the Bloomsbury Group. As I stand surveying the books, pictures and ceramics, I feel a frisson of pleasure knowing that I am imbibing the very atmosphere where the Woolfs would partake in philosophical and literary banter, with the likes of E. M. Forster, Duncan Fry, Lytton Strachey and T. S. Eliot. As Virginia recalls, “… we sit, eat, play the gramophone, prop our feet up on the side of the fire and read endless books.”

Vintage Snapshot Print, June 1926

NPG Ax142597

Image: [CC BY-NC-ND 3.0]

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The river reflected whatever it chose of sky and bridge and burning tree, and when the undergraduate had oared his boat through the reflections they closed again, completely, as if he had never been. There one might have sat the clock round lost in thought. Thought—to call it by a prouder name than it deserved—had let its line down into the stream. It swayed, minute after minute, hither and thither among the reflections and the weeds, letting the water lift it and sink it until—you know the little tug—the sudden conglomeration of an idea at the end of one’s line: and then the cautious hauling of it in, and the careful laying of it out? Alas, laid on the grass how small, how insignificant this thought of mine looked; the sort of fish that a good fisherman puts back into the water so that it may grow fatter and be one day worth cooking and eating. I will not trouble you with that thought now, though if you look carefully you may find it for yourselves in the course of what I am going to say.

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Virginia’s bedroom is a separate annexe to the main house, accessible through the kitchen door and out into the garden behind. As she famously wrote whilst the extension was being constructed, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Originally intended as her private workroom, she quickly discovered, however, it would not be suitable for creating prose: “I cannot yet write naturally in my new room because the table is not the right height, & I must stoop to warm my hands. Everything must be absolutely what I am used to.”

Her stream of thoughts had to find an outlet elsewhere and thus, she would ensconce herself in the writing lodge at the end of the garden to compose her literary outpourings, the weather-boarding building nestling amidst the apple trees of the orchard and the long shadow of the Church of St Peter’s steeple beyond, affording privacy and the stillness to think.

Vintage Snapshot Print, June 1926

NPG Ax142596

Image: [CC BY-NC-ND 3.0]

© National Portrait Gallery, London

What does one mean by ‘the unity of the mind’? I pondered, for clearly the mind has so great a power of concentrating at any point at any moment that it seems to have no single state of being. It can separate itself from the people in the street, for example, and think of itself as apart from them, at an upper window looking down on them. Or it can think with other people spontaneously, as, for instance, in a crowd waiting to hear some piece of news read out. It can think back through its fathers or through its mothers, as I have said that a woman writing thinks back through her mothers. Again if one is a woman one is often surprised by a sudden splitting off of consciousness, say in walking down Whitehall, when from being the natural inheritor of that civilization, she becomes, on the contrary, outside of it, alien and critical. Clearly the mind is always altering its focus, and bringing the world into different perspectives. But some of these states of mind seem, even if adopted spontaneously, to be less comfortable than others. In order to keep oneself continuing in them one is unconsciously holding something back, and gradually the repression becomes an effort. But there may be some state of mind in which one could continue without effort because nothing is required to be held back. And this perhaps, I thought, coming in from the window, is one of them.

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

In October 1928, Virginia was invited to deliver lectures at Newman and Girton Colleges, which were the only women’s colleges at Cambridge at that time. Centred around the topic of women and fiction, the talks were revised and expanded and published a year later as A Room of One’s Own. A partly fictionalized narrative, Virginia assesses the importance of nineteenth-century female novelists and the state of contemporaneous fiction, finishing her thesis by exhorting women everywhere to take up the pen and engage in literary battle, thus rendering the book to be one of the most important feminist tracts of the twentieth century.

Moreover, the narrator poses the question, “What is the state of mind that is most propitious to the act of creation?” Acknowledging the “prodigious difficulty” of creating a work of genius, she concludes that circumstances generally conspire against it, owing to the indifference of the world with its multitude of distractions and discouragements. Indeed, believing that genius is transcendent, the narrator posits that the mind of the artist is vulnerable to outside influence, notwithstanding her own domestic arrangements, and must, therefore, “be incandescent … There must be no obstacle in it, no foreign matter unconsumed.”

Vintage Snapshot Print, June 1926

NPG Ax142587

Image: [CC BY-NC-ND 3.0]

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Therefore I would ask you to write all kinds of books, hesitating at no subject however trivial or however vast. By hook or by crook, I hope that you will possess yourselves of money enough to travel and to idle, to contemplate the future or the past of the world, to dream over books and loiter at street corners and let the line of thought dip deep into the stream.

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Forever doting, Leonard was also an author in his own right, writing novels, essays and pamphlets. Together with Virginia, the Woolfs established the Hogarth Press, named after their house in Richmond, in which they began hand-printing books. Within ten years, the Press had become a full-scale publishing house, issuing Virginia’s novels, Leonard’s tracts and, among other works, the first edition of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land.

And yet despite Leonard’s spousal support and literary husbandry, Virginia still preferred to have a room that she could call her own, believing that “a lock on the door means the power to think for oneself”, where she could stoke the fire of her own intelligence, allowing the incandescence of her art to burn forever brightly, her fiction the very crucible of her unique truth.

Vintage Snapshot Print, June 1926

NPG Ax142589

Image: [CC BY-NC-ND 3.0]

© National Portrait Gallery, London

What is meant by ‘reality’? It would seem to be something very erratic, very undependable—now to be found in a dusty road, now in a scrap of newspaper in the street, now a daffodil in the sun. It lights up a group in a room and stamps some casual saying. It overwhelms one walking home beneath the stars and makes the silent world more real than the world of speech—and then there it is again in an omnibus in the uproar of Piccadilly. Sometimes, too, it seems to dwell in shapes too far away for us to discern what their nature is. But whatever it touches, it fixes and makes permanent. That is what remains over when the skin of the day has been cast into the hedge; that is what is left of past time and of our loves and hates.

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Strolling around the garden, once Leonard’s pride and glory, I cast my gaze towards the distant hills and River Ouse, breathing in deeply the autumnal air. I start to wonder if, in our post-feminist world, Virginia’s words have lost their significance. And yet perhaps, at a more existential level, they are indeed more pertinent than ever if we consider “room” to encapsulate not only the confines of an area inside a building but the inner consciousness of our very own minds.

In her heartbreaking suicide note to Leonard, Virginia said, “I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate.” Her “room” was being violated again by noise and disorder, becoming all too much for the novelist to bear. Her decision to walk out early one Tuesday morning in March 1941 and drown herself in the Ouse was an act we may feel it difficult to come to terms with; nevertheless, we can all well empathize with her endorsement that an authentic life is the one that pays homage to reality above all else, whatever its outcome, in its quest to find unity of mind and solace of soul.

Vintage Snapshot Print, June 1926

NPG Ax142592

Image: [CC BY-NC-ND 3.0]

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Here I would stop, but the pressure of convention decrees that every speech must end with a peroration. And a peroration addressed to women should have something, you will agree, particularly exalting and ennobling about it. I should implore you to remember your responsibilities, to be higher, more spiritual; I should remind you how much depends upon you, and what an influence you can exert upon the future. But those exhortations can safely, I think, be left to the other sex, who will put them, and indeed have put them, with far greater eloquence than I can compass. When I rummage in my own mind I find no noble sentiments about being companions and equals and influencing the world to higher ends. I find myself saying briefly and prosaically that it is much more important to be oneself than anything else …

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

[Lady Ottoline Morrell’s portraits of Virginia Woolf are courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

They have been altered from sepia to black and white and slightly cropped along each border.]

Post Notes

- Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

- Monk’s House, National Trust

- Virginia Woolf portraits at the National Portrait Gallery

- The Story of Omega Workshops at the Tate

- Writers & Artists Spirituality Series

- T. S. Eliot: A Man Out of Time

- E. M. Forster: The Celestial Omnibus

- The Spirituality of Duncan Grant

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Kathleen Raine: The Land Unknown

- Mason Currey: Daily Rituals, Women at Work