Photograph: © Victor Kossakovsky + © Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier

The secret life of beasts

“revere what is in front of you…

fight for it to remain”

CAROL RAPHAEL is an American book editor, writer on the arts and photographer currently living in Portland, Oregon. Her writings have appeared in magazines such as EnlightenNext magazine (formerly known as What Is Enlightenment? magazine) and the German publication Evolve, as well as newspapers and various national and international arts periodicals. She has travelled widely and lived in France, Italy and the UK. Now she cares for two goats who help her clear blackberries and ivy from the back woods.

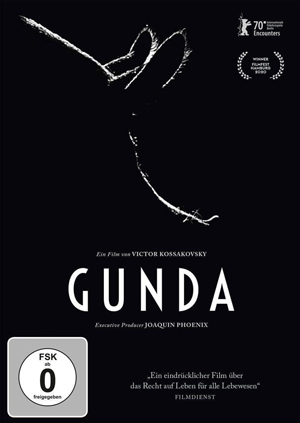

In this month’s guest post for The Culturium, Carol elegantly examines two nature films—Victor Kossakovsky’s Gunda and Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier’s The Velvet Queen; each so starkly different in terms of their cinematographic aesthetic and yet both offering a shared insight into the intimate lives of creatures that bless this hallowed earth, from a humble sow and her piglets snuffling around in a farmyard to a majestic snow leopard prowling the mountain slopes of Tibet.

Victor Kossakovsky, Gunda

The invention of moving pictures transformed the telling of a good yarn. Thanks to the movies, everyone hears and sees the same story, the one before our eyes and ears, not the one we imagine in our mind’s eye when we read a novel or listen to a storyteller. With cinema, we all see the same blue dress and know the good guys from the bad, as dictated by the director and cinematographer. Going to the movies is a communal experience.

Photograph: © Victor Kossakovsky

Today, well into the 21st century, film can take us far beyond narrative fictions and into a deeper encounter with the very real world of life on the planet that many of us are unlikely to experience on our own. Werner Herzog took his camera into the depths of the Antarctic ocean in Encounters at the End of the World. Philip Gröning brought us inside the Grande Chartreuse, a remote, insular monastery high in the French Alps with Into Great Silence. And NASA’s footage in the documentary Apollo 11 transported us to the other side of the moon.

Photograph: © Victor Kossakovsky

Two recent films have exploited the capacity of film to go where few care to tread—to a rare intimacy with animals that is at once mysterious and eternal. One of the films features farm animals, those creatures who live at the mercy of us humans; the other aims its telephoto lens on wild, increasingly remote animals who’ve managed to escape the predation of human beings, the singular planetary species without a predator of its own. Both documentaries were released in 2021 and both are enthralling, eloquent, gorgeous and humbling.

Photograph: © Victor Kossakovsky

In Gunda, the great Russian filmmaker Victor Kossakovsky places his camera in a farmyard, where he documents the daily life of the eponymous pig and a few of her barnyard companions. Gunda has given birth and the film tracks her litter, a few chickens and some cows. No humans invade the scene and the soundtrack is as lush as the black and white cinematography and entirely natural, whether it’s the susurration of suckling piglets, wings flapping, cows lowing or wind rustling in the leaves.

Photograph: © Victor Kossakovsky

For an hour and a half, the viewer is immersed in this familiar yet alien world. We’re inside the pigsty, rain pummeling, with Gunda and her farrow. We view at eye-level a one-legged chicken who dauntlessly navigates uneven terrain. We gaze into the placid eyes of a cow as it repeatedly flicks away annoying flies with its tail. This is a sentient world, alive and intelligent, and Kossakovsky’s compassionate eye patiently and tenderly reveals its nuances and sensitivities. Kossakovsky had known a beloved pig when he was four years old and this film is his homage to that unbounded relationship only an innocent child can know.

Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier, The Velvet Queen

The Velvet Queen, or La panthère des neiges as it’s entitled in the original, more poetic French, is another feat of creative filmmaking, one that entailed extreme physical challenge to make. Shot in the harsh, isolated regions of the Tibetan highlands, it documents a pursuit of the elusive snow leopard by the meticulous wildlife photographer and co-director Vincent Munier, adventurer and writer Sylvain Tesson, cinematographer Marie Amiguet, and her assistant.

Photograph: © Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier

I first learned about the solitary feline in Peter Matthiessen’s luminous book, The Snow Leopard, which recounts two months he spent searching for the animal in Nepal. Matthiessen, a Zen Buddhist, never succeeded in laying eyes on the snow leopard but the quest following shortly after the death of his wife ignited a rich and meaningful inner journey as he contemplates loss, the impermanence of life and the great beauty in which he finds himself.

Photograph: © Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier

I wonder if the impassioned seekers of The Velvet Queen would have been as sanguine as Matthiessen if they hadn’t spotted a snow leopard, which they finally do during the last days of a three-week trek. Tesson, whose commentary accompanies an ethereal score composed by Warren Ellis and Nick Cave and stunning cinematography—harsh scree, a yak in moonlight, fleeing antelope, swirling mist—was determined to see the evasive leopard. He, too, was grieving the end of a relationship and was, moreover, still dealing with the repercussions of a serious fall from a rooftop; seeing the snow leopard was both an obsession and a cure for him.

Photograph: © Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier

Tesson and his companions succeeded in encountering the leopard in no small part due to the extraordinary patience and exacting requirements Munier demanded. Munier teaches Tesson the fundamentals of a good blind essential for tracking animals and tutors him in the art of sitting motionless in the brutal cold for hours and days on end. As Tesson noted in his journal, ‘patience is a supreme virtue; it helps you love the world’.

Photograph: © Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier

In addition to observing other magnificent animals along their way, the small four-person crew sip tea and bunk with a local family, whose spirited children provide relief and warmth to the austere rigours of the expedition. Yet, the most searing and unforgettable moments of the film, which is filled with images of grandeur, are when the snow leopard looks directly and steadily into the fixed lens of a camera aimed directly at its small nearby perch. It would be demeaning to interpret or anthropomorphize that stare; suffice it to say that it is mesmerizing and awe-inspiring.

Gunda ends on a no less moving moment but one shadowed by heartbreak.

Photograph: Fair Use

Filmed with immense respect and compassion for animals and more nuance than a National Geographic blockbuster, both films dignify rather than fetishize their subjects. The human perspective is kept in check, reminding us that we are one among many species on this planet and that consciousness is far-reaching and pervasive.

At the end of The Velvet Queen, Tesson summarizes lessons he learned in the wilds of Tibet, insights we’d all be wise to embrace and which apply equally to Gunda and The Velvet Queen:

revere what is in front of you

hope for nothing

delight in what crops up

have faith in poetry

be content with the world

fight for it to remain

Post Notes

- GUNDA official website

- Carol Raphael: The Beauty We Create

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Xavier Beauvois: Of Gods and Men

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- Spiros Stathoulopoulos: Meteora

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- Edward A. Burger: Amongst White Clouds

- Kim Ki-duk: Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring