Landscape fragments

“In the middle of our walk of life,

I found myself within a forest dark,

for the straightforward pathway had been lost.”

—Dante Alighieri, “The Divine Comedy”

TOBIAS WILKINSON is a British artist with his work centred on relief sculpture, photography and painting. He is concerned with and interested in the sublime and the action of the unconscious mind in the creative process. He was born and grew up in North London in a thriving artistic household. His father, mother and all four grandparents were all artists. He initially decided to pursue a career as a soldier but eventually succumbed to what his family calls “art disease” and graduated from Central St Martins College of Art, BA Fine Art and London College of Communications, MA Documentary Photography. His work is held by a number of private collections in the UK and overseas and he is a member of the Royal Society of Sculptors.

In this month’s guest post for The Culturium, Tobias examines how his artistic appreciation for the natural world unfolds through his stunning black and white photographic series, German Forest Primer.

I have drawn inspiration from landscapes around the world but until I got married and came to live in the Taunus region in the German state of Hessen, I had never spent time in a forest. What interested me was that the forest seemed to provide the same emotional and spiritual appeal to German people as the sea does to the British and so I decided to explore this further.

Over 30 percent of Germany is woodland and over 40 percent of Hessen is forested. The Taunus forest, where I now live, covers around 1000 square miles and dates from the Devonian period, 400 to 320 million BCE. Human habitation of the hill behind me can be documented to around 4 BCE when the Celts built and inhabited the Altkoenig hill fort complex. The hills and fort were then occupied and reinforced by the Romans until about 250 CE when they were abandoned to the Germanic tribes of the Rhine. The Taunus rises to about 800 metres and is a mixture of deciduous and coniferous forest.

My interest as an artist is in the sublime experience of this forest and the spiritual and emotional values that it brings. Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher born in 544 BCE, said, ‘No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.’

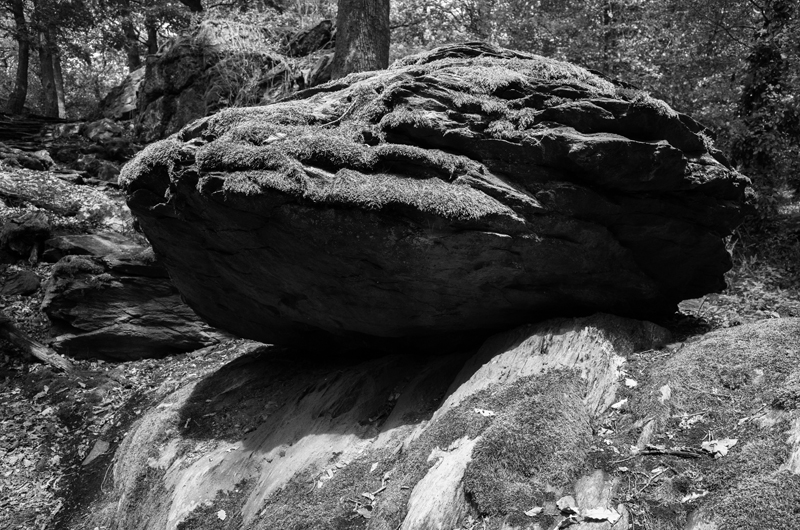

The same can be said of forests. They not only have a universal appeal as an experience of the sublime and a restorative for the soul but have always held religious, aesthetic and mythical significance for peoples around the world. The forest, like the river, is always changing. And like the river, the forest lives in different time zones. It moves at different speeds. The rock formations that form the backbone of the forest structure over 300 million years ago contrast poignantly with the short life span of the forest butterflies that alight upon them. To be immersed in the forest is to join with matter that is always moving at different speeds in harmony and symbiosis with itself.

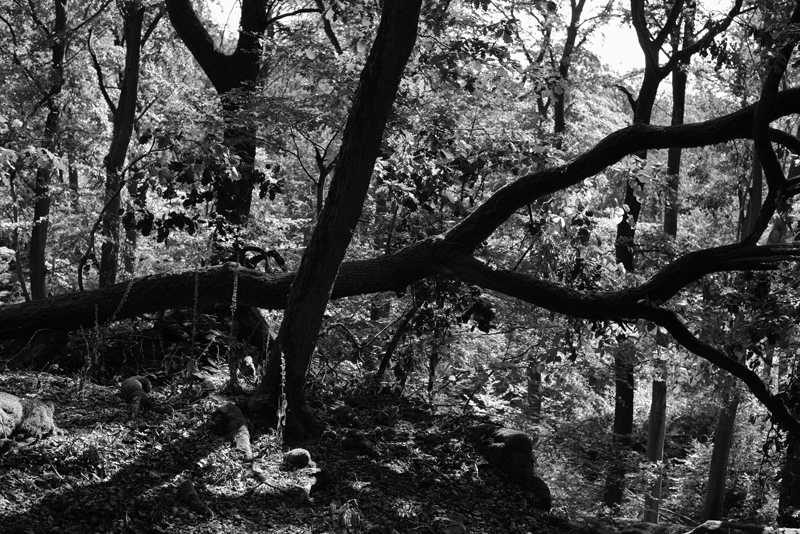

The libraries of universities in Germany are littered with philosophical treatises addressing the significance of the German forest. From Grimms’ fairy tales to the archetypes of Carl Jung, from The Lord of the Rings to Star Wars, the forest serves as a well-worn metaphor for the hero journey of mythological storytelling or the unconscious mind of psychoanalysis. ‘For those who enter fairyland, there is no going back. They must go on and go through it,’ said R. MacDonald Robertson in Selected Highland Tales. Nonetheless, the forest exists as more than a metaphor for mankind’s internal drama or what American photographer Robert Adams describes as ‘the shadow world of romantic egoism’.

There are many different ways to approach a forest. Mine is from the cultural and spiritual perspective. What distinguishes the physical experience of the forest from other kinds of landscape is that you are not on it but in it. The experience is of being within a living physical organism. Once in the forest, there is little in the way of sweeping vistas or distant horizons. Everything is close by with variations of light and dark created by the canopy and vegetation. The forest represents benign resources such as food, material, shelter and refuge but is also a place of threat, of wild animals, hidden dangers and the unknown. It is the essence of the sublime experience.

However, it is not a wilderness. We live in the Anthropocene age. Nothing in the forest remains untouched by human hand. As Robert Adams also says, ‘Unspoiled places sadden us because they are in an important sense, no longer true.’ (Beauty in Photography.) The German forest is a crisscross of forestry tracks, people tracks and cycling paths. It is a patchwork of fir plantations and deciduous trees. Above all, the forest is a managed place. It is a resource with different interests. It is both a timber factory and a biodiversity centre. Timber is grown and harvested, storm-damaged and overcrowded trees are felled and great care is taken to ensure the preservation of the ecology of the forest through the creation of undergrowth and cover.

The forest also exists as a tourism resource. It provides a place for walking, cycling and running. Hiking (‘Wandern’) and experiencing the forest is a key German cultural marker. The mid-19th century saw changes in modes of travel, which democratized an activity previously the preserve of pilgrims, poets and romantics as city dwellers gained access to the forest and increased its cultural significance. Most recently in the pandemic of 2020/21, with the significant increase in numbers seeking the emotional balm and escape of the forest, the human burden on the forest increased.

The forest also accommodates a wide variety of wildlife. Larger species such as deer and wild boar regularly hunted by very traditional and long-established hunting clubs (Saint Hubertus, the patron saint of hunting) is popular. Ties to religion are also strong, with cemeteries, hermit refuges and small churches dating to the 8th century unexpectedly encountered. It further represents a vital biodiversity resource. Drinking water for the Main valley, including the city of Frankfurt, comes from the Taunus Hills and is collected by a complex system of water pumping and collection stations, some rather spectacular 19th-century creations, buried deep in the woodland. It also plays a vital part in CO2 collection and its influence on climate change, and valuable roles in weather pattern influence, soil erosion and landslide prevention.

And so, it will be clear that I am interested in the Taunus forest as a place, not as a concept. The concept of ‘forest’ as a Platonic form does not get me very far. In this sense, philosophers and artists are somewhat opposed, the latter moving from the abstract to the particular rather than vice versa. The intention of my work is simple: to find what something feels like, rather than just what it looks like, through a synthesis of geography, autobiography and metaphor. To do that, I endeavour to create space for the imagination to work. As Picasso said, ‘Love must be proven by facts, not by reasons.’

Post Notes

- Feature image: © Tobias Wilkinson, German Forest Primer

- Tobias Wilkinson’s website

- John Devitt: Cloud Illusions

- Danila Tkachenko: Escape

- Ron Rosenstock: The Invisible Light

- Ansel Adams: The Search for Beauty

- Roy Whenary: Open Awareness

- Jerry Katz: Let the Scene See You

- Andy Richter: Serpent in the Wilderness

- Laura Emerson: Deep Sea Contemplation

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme