Thomas Merton | Documentary

A beautiful and holy vision

“I don’t know when in my life I have ever had such a sense of beauty and spiritual validity running together in one aesthetic illumination.”

—Thomas Merton

PHILIP BROWN is an independent researcher in the field of Contemplative Studies. He spent his working life teaching children with severe and multiple disabilities, developing training programmes, SoSAFE!, to prevent their physical and sexual abuse. Baptized and confirmed in the Church of England, he has practised meditation for over 40 years. For the past two decades, he has studied and practised the Dzogchen Teachings of Tibetan Buddhism; prior to that, he practised Transcendental Meditation and Vipassana (Insight) Meditation.

A regular contributor to The Culturium, in this month’s feature, Philip offers us a scintillating extract from Thomas Merton’s journal written during his extended trip to Asia. Akin to his renowned revelation in downtown Louisville at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, Thomas Merton describes a moment of satori precipitated by a visit to the majestic Buddhist sculptures of Polonnaruwa in Sri Lanka.

o0o

The American, Trappist monk, Thomas Merton (31st January 1915–10th December 1968), is widely regarded as one of the most important Christian contemplatives of the twentieth century. His writings on Christian contemplative prayer and interfaith dialogue were a catalyst for the rediscovery and blossoming of Christian contemplative practice in the Western World.

On 15th October 1968, Merton commenced a tour of Asia starting at Bangkok, Thailand. He travelled through India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and then returned to Bangkok in December, where he spoke at a conference of Asian monastic orders. Tragically, he died accidentally during that conference. His personal travel notes were later edited and published as The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton (1973/1975). This article describes his epiphanic contemplative experience at the ancient Buddhist site of Polonnaruwa in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) as described in the Journal.

Merton’s understanding of Buddhism

Thomas Merton had for many years sought direct, personal, interfaith dialogue with practitioners of non-Christian monastic orders. On his tour of Asia in 1968, he had dialogues with a number of Buddhist teachers and practitioners, including the English Theravadin monk, Phra Khantipalo, in Bangkok and various Tibetan Buddhist teachers in the Himalayas. These Tibetan teachers included Chatral Rinpoche and, most notably, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.

Prior to this, Merton pioneered Christian-Buddhist dialogue through his communications with prominent Buddhists, such as the Japanese Zen scholar, D. T. Suzuki, and the Vietnamese Zen monk and teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh, having familiarized himself sufficiently with Zen Buddhism to write the books Zen and the Bird of Appetite and Mystics and Zen Masters. He undoubtedly had a better understanding of Buddhist concepts than most non-Buddhists of his day and the Dalai Lama praised him as having a more profound understanding of Buddhism than any other Christian he had met thus far.

Merton’s diary entries about his experience at Polonnaruwa included the name Ananda and the Buddhist terms “Dharmakaya”, “Sunyata” and “Madhyamika”. To fully understand his description of this experience, it is necessary to know what he understood by these terms. Based on the Buddhist reference material, which Merton is known to have consulted and notes he made in his Asian Journal, he is likely to have understood them as follows:

• Dharmakaya is the Sanskrit term for “the cosmic body of the Buddha, the essence of all beings”.

• Sunyata means that both phenomena and the Absolute are “empty” or “void”. “Phenomena are relative and lack substantiality or independent reality”; while “the Absolute is devoid of empirical form”.

• Madhyamika is a method of philosophical enquiry and debate, which deconceptualizes the mind and disburdens it of all notions. The practitioner of Madhyamika does not allow themselves to be entangled in views and theories and observes the nature of things without standpoints. The method is designed as a catalyst for going beyond dualistic conceptual thinking to insight into, and eventual continuous abidance in, ever-present, pure, nondual awareness. Through this awareness, Sunyata and Dharmakaya can be directly apprehended.

• Ananda is the name of the Buddha’s favourite disciple.

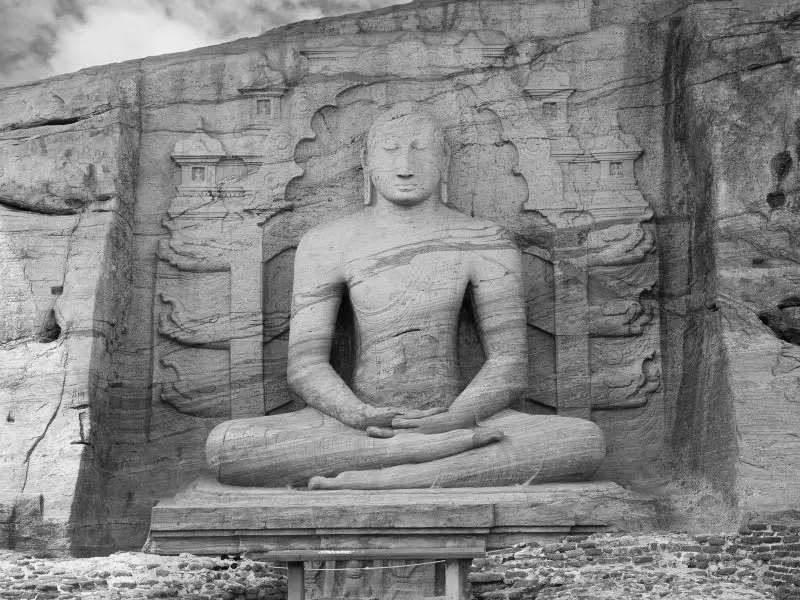

Image: © Sri Lankan Art Eka

Merton’s experience at Polonnaruwa

According to the editors of his Asian Journal, it is a matter of public record that Merton unequivocally reaffirmed his Christian vocation during the Bangkok Conference. Nonetheless, as shown below by his reaction to the ancient Buddhist statues and caves of Polonnaruwa, Merton’s spiritual growth was enriched by contact with other religious traditions. In response to visiting Polonnaruwa, he wrote:

Polonnaruwa was such an experience that I could not write hastily of it and cannot write now, or not at all adequately.

The following excerpts from his Asian Journal demonstrate the visceral and palpable impact which religious art can have on those who view it. Furthermore, given Merton’s “contemplative” rather than just “religious”,”‘sacred” or “spiritual” response to the religious art of Polonnaruwa, this art can also be regarded as contemplative art, as defined by the author in his article, “Contemplative Art—A Supreme Gift“, on this website.

Being in the presence of the statues of the Buddha at Polonnaruwa had a profound effect on Merton as a contemplative practitioner. As revealed below, his subsequent journal notes detail an epiphanic contemplative experience:

Polonnaruwa [is a] vast area under trees … [Approaching it] the path dips down to Gal Vihara: a wide, quiet, hollow, surrounded by trees. A low outcrop of rock, with a cave cut into it, and beside the cave a big seated Buddha on the left, a reclining Buddha on the right, and Ananda I guess, standing by the head of the reclining Buddha. In the cave another reclining Buddha … I am able to approach the Buddhas barefoot and undisturbed, my feet in wet grass, wet sand. Then the silence of the extraordinary faces. The great smiles. Huge and yet subtle. Filled with every possibility, questioning nothing, knowing everything, rejecting nothing, the peace not of emotional resignation but of Madhyamika, of Sunyata, that has seen through every question without trying to discredit anyone or anything—without refutation—without establishing some other argument. For the doctrinaire, the mind that needs well-established positions, such peace, such silence, can be frightening. I was knocked over with the rush of relief and thankfulness at the obvious clarity of the figures, the clarity and fluidity of shape and line, the design of the monumental bodies composed into the rock shape and landscape, figure, rock and tree. And the sweep of bare rock sloping away on the other side of the hollow, where you can go back and see different aspects of the figures.

Looking at these figures I was suddenly, almost forcibly, jerked clean out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and an inner clearness, clarity, as if exploding from the rocks themselves, became evident and obvious. The queer evidence of the reclining figure, the smile, the sad smile of Ananda standing with arms folded (much more ‘imperative’ than Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa because completely simple and straightforward). The thing about all this is that there is no puzzle, no problem, and really no ‘mystery’. All problems are resolved and everything is clear, simply because what matters is clear. The rock, all matter, all life, is charged with Dharmakaya … everything is emptiness and everything is compassion. I don’t know when in my life I have ever had such a sense of beauty and spiritual validity running together in one aesthetic illumination … The whole thing is very much a Zen Garden, a span of bareness and openness and evidence, and the great figures, motionless, yet with the lines in full movement, waves of vesture and bodily form, a beautiful and holy vision.

References, Resources & Post Notes

- Burton, N., et al., Eds. (1975), The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton, New York, New Directions Books.

- Griffin, Jim. (2017), “The Engaged Contemplative Spirituality of Thomas Merton”, Beshara Magazine (4), The Spirituality of Thomas Merton | Beshara Magazine

- Merton, Thomas, (1968), Zen and the Birds of Appetite, New York, New Directions.

- Merton, Thomas. (1999), Mystics and Zen Masters, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Thomas Merton Center, (2023), “Thomas Merton’s Life and Work”, Thomas Merton Center, accessed 11-07-23 at merton.org

- T.R.V. Murti. (1955), The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, A Study of the Madhyamika System, London, Allen & Unwin.

- Fred Bahnson, “On the Road with Thomas Merton”, Emergence Magazine

- Thomas Merton, Seeds of Contemplation, “Pure Love”, read by Samaneri Jayasāra

- Philip Brown: Contemplative Art—A Supreme Gift

- Philip Brown: Mysticism and Mystic Experience

- Fakhruddin ‘Araqi: Divine Flashes

- Philip Brown: Transcendence through Beauty in Art & Nature

- Cheval Sombre: The Wilderness of Music—Time Waits for No One and Thomas Merton

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Antony Gormley: Sculpted Space Within and Without

- Ajahn Sumedho: The Sound of Silence