Divine inheritance

You are awake in something which everyone knows but seems to have forgotten.

It draws on a kind of hidden regard for what, in each of us,

works gently making its way into the world—a Self that belongs to everyone.”

THE WORLD PEACE PROJECT (1973–present) is an ongoing work of contemporary art that combines elements of design, performance and parable to conceive and explore imaginable futures. The project embodies the essence of a preferable world by extending our current understanding of the possible. As an ongoing work of storytelling, the project reveals how things once hidden suddenly take voice and become available.

In this month’s guest post for The Culturium, the project’s creator and curator, Ted Somogyi, who has exhibited all over the world including WW Gallery, London, MASS MoCA and The Smithsonian Institution, reveals how the initiative works to reposit the store of what is being lost in a world replete with noise and fakery—silence. He is currently affiliated with the San Francisco Academy of Art.

I grew up on the coast of New England in an old ship captain’s house not far from the American Shakespeare Theater in Stratford, Connecticut. My father was a painter and my mother a writer. They worked jobs neither held in high regard. Raised a family of five. And lived convinced of a certain middle-class respectability. It was an upbringing that provided everything, except a way out.

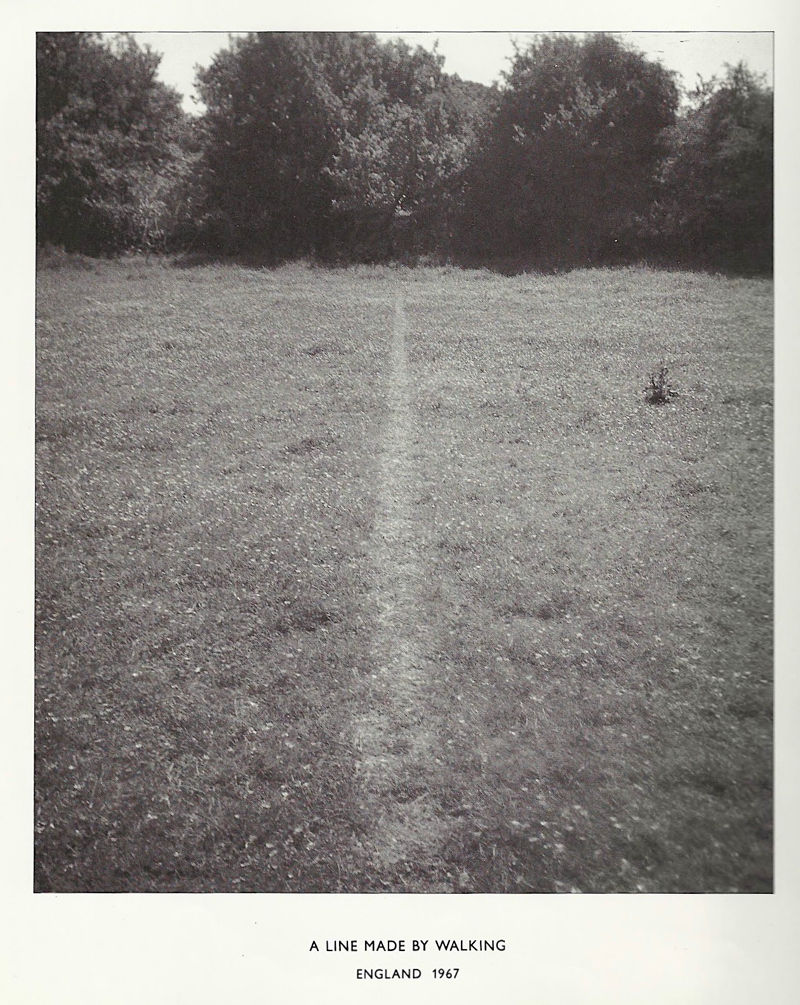

I spent my summers playing baseball and my winters in the local public library. The latter a way of staying warm and away from the raw sheet metal we called winter. I came across a photograph one day, taken by an unknown British artist named Richard Long. It showed only a faint path through an otherwise ordinary grassy field in Wiltshire, England. It was titled: A Line Made By Walking. A short description referred to it as a work of art. It was in this library, at the age of 15, that I began to see the world differently.

As the 1970s opened, I was enrolled at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, while the 20th century was coming to a close, taking the American dream with it. This ended an era often described as the largest shopping spree in history—one that fossilized waking state consciousness through pervasive advertising. In response, prompted by whatever it is that moves the young, I was meditating regularly, while making plans for a trip to India to study the Vedas.

The evidence of a successful miracle is the return of hunger.

—Fanny Howe

In the arts, after decades of emotive abstraction, artists were looking back into the world again. Around this time a more contemporary and critical art began to emerge. In the visual arts it was called Institutional Critique and it posed a systematic enquiry into the workings of art institutions. One of the best examples was the work of German artist Hans Haacke, who created art that exposed connections between money, art and politics.

Hans Haacke, one of the most consistent and uncompromising figures of American art, who has spent half a century mining the terrain around and behind works of art, and revealing the hidden operations of powerful associations, art museums very much among them.

—Jason Farago, Hans Haacke, at the New Museum, Takes No Prisoners, New York Times, 2020

In short, it was no longer advisable to see discrete objects without taking into account the systems that privilege them. Generally speaking, the arts are found in museums, galleries, theatres and more commonly in places where people gather. That is, art is framed by the setting in which it is encountered. And hidden within these various institutions are biases that exert tremendous influence over what is called art.

For the next several decades it was as though Institutional Critique had turned the lights on and restored the power. Things once hidden—original editions of H. W. Janson’s History of Art, where not a single woman is mentioned—scurried out of the shadows. Whether suddenly showing long concealed works or designing new “inclusive” shows, artists and critical practices more generally began to question long-standing, obsolete practices.

In the larger artworld, objects were becoming a secondary consideration, while the act or purpose for making them ascended to prominence. Artists also began to question a style of social framing that first squeezes world-making into a deliverable logic, before installing it as a form of self-evident history. I was influenced by Haacke and others, Richard Long, Yoko Ono, the PULSA group to mention a few. Encountering these works encouraged me to contend with new forms of expression.

… a work of art is always defined by two essential criteria: meaning and embodiment, as well as one additional criterion contributed by the viewer: interpretation.

—Arthur C. Danto, What Art Is, 2013

Artists were now actively looking for ways to embody and represent the more common side of daily life. Gordon Matta-Clark cut holes in abandoned Hudson River pier buildings to illuminate the dark and honour the past, while Mierle Ukeles washed the staircase and entryway of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum in Hartford, CT. Drawn to the idea of cleaning up by letting the light in, I too began to move away from the galleries and despoiled commerce of modern art. Clearly, the inner world was calling; what to do with these periods of deep meditation and the vast ancient history of the Vedas? And so it was, the World Peace Project was born.

As time passed, and the project developed, I began to look more clearly at what I was doing. Of comfort to a fallen Catholic, exploring consciousness replenished my sense of the heavenly by placing it within. Described variously as the Self, the Observer, Lord of the Chariot, Samadhi, and Silence, (“Be still and know that I am God”, Psalm 46:10). It is a state of inner wakefulness with no object of thought or perception. Just pure consciousness aware of its own unbounded nature. It is wholeness, aware of itself, devoid of differences, beyond the division of subject and object.

Traditional accounts of mind not ordinarily discussed in the West describe it much like an ocean. In this view, the mind has an active surface with increasingly more silent depths below. At every level, all diversity in the cosmos is nothing more than the animated silence of a coalesced wholeness. My universal wholeness and that of the cosmos are one and the same.

Consciousness is traditionally portrayed as a field both eternally awake and equally present everywhere. But something both eternally awake and equally present cannot be represented—it has to be lived. And to live it by sitting in a museum or on a mountain, eyes closed, is also a work of art: it may not represent, as much as it embodies, meaning.

EDMUND (ACT 4 SCENE 1)

Became the sun, the hot sand, green seaweed anchored to a rock, swaying in the tide. Like a saint’s vision of beatitude. Like a veil of things as they seem drawn back by an unseen hand. For a second you see—and seeing the secret, are the secret. For a second there is meaning!

—Eugene O’Neill, Long Day’s Journey into Night, 1956

Edmund Tyrone, in Long Day’s Journey into Night, laments the loss of meaning when an unseen hand lets the veil fall. With meaning short-lived, his experiences float, unanchored, like gems in search of a setting. And hidden once again, according to the Mundaka Upanishad, “… is that, by knowing which, everything becomes known.”

IMAGINABLE FUTURES

Now, the sum of all this is strangely at odds with a world in apocalyptic freefall. But then the news we see, “… the oblique contempt with which we are depicted to ourselves,” as poet Adrienne Rich once said, may not be the entire story. Then suddenly I remember, it is no longer advisable to see discrete objects without taking into account the systems that privilege them.

Over the course of this project, I have moved according to the path I was being offered. I have travelled extensively and met many remarkable people. Indeed, a small sampling of a much larger world. Of all that’s happened, one thing stands out: no one bothers someone sitting quietly with their eyes closed. I don’t necessarily have the words for it but it goes something like this: for a moment you are silent. You are awake in something which everyone knows but seems to have forgotten. It draws on a kind of hidden regard for what, in each of us, works gently making its way into the world—a Self that belongs to everyone.

The fulfilment of our aesthetic longing will always be provided by works of art. Ours is a history, after all, of made things. But what art is has changed. Much of today’s art is in keeping with the fluid nature of our interconnected world. Like the world, consciousness is not static, it flows, expands, seeking to become all that it sees. And it is here, that a preferable future is emerging because interpretation is still incumbent upon the viewer.

The gods produce meaning in the margins of the imaginable where the other news gathers prior to being heard. Unmanaged and without approval, motivated perhaps by an unseen hand, we recognize our oneness with the sacred first, then bestow it commonly upon the world where it returns as something divinely inherited. Then the gods move on in search of something else, leaving behind a faint line made by their walking.

Post Notes

- Feature image: © Mike Robinson, Two Roads Desert

- World Peace Project

- Genealogies of Modernity

- Spontaneous Interventions

- PULSA Group

- The No Show Museum

- John Cage Trust

- Suzanne Moss: Seeking Sanctuary

- Roberta Pyx Sutherland: Greater Silence

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme