Crazy wisdom

“Remembering yourself as a buddha is the most precious experience

because it is your eternity, it is your immortality. It is your very existence.

You are one with the stars and the trees and the sky and the ocean.

You are no longer separate.”

—Osho

BORN AND RAISED in the United Kingdom, Subhuti Anand Waight graduated from Bristol University with a degree in Politics and Philosophy. He then trained as a journalist and became a political reporter in the British Houses of Parliament. In 1974, he became interested in spirituality and studied with Oscar Ichazo, the Bolivian mystic, and Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, the Sufi mystic. In 1976, he travelled to India to meet Osho, then known as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, in his ashram in Pune. He became initiated as his disciple and for the next 14 years lived and worked in Osho’s communes, first in Pune and later at Rancho Rajneesh in Oregon, USA. He stayed with Osho until the mystic died in January 1990. Since then, Subhuti has worked as an author and freelance journalist, dividing his time between the United Kingdom, Europe and India.

In this month’s guest post for The Culturium, Subhuti outlines a fascinating account of his time spent with Osho and his insightful observations on one of the world’s most enigmatic spiritual teachers.

Nobody will argue with me when I say that the Indian mystic Osho, formerly known as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, is a controversial figure. In fact, this is the only description of him on which everyone agrees. Beyond it, discussion tends to polarize: was he a good guy or a bad guy? Was he a mystic or a con man?

This is why books about Osho fall into two opposing camps: for and against. Those that are for him, attempt to show the mystic in the best light, meaning that they emphasize what appear to be the ‘good’ aspects of Osho’s life and try to avoid what they think is ‘bad’. Books that are against him do the reverse: emphasizing what they consider to be ‘bad’ and ignoring the ‘good’.

As far as I am concerned, Osho was beyond these categories. Having been initiated by him as a disciple, or sannyasin, way back in 1976, and having ridden the roller coaster of life with him, and later without his physical form, I know that he does not fit into any stereotype and so, even today, he appears to be paradoxical and hard to define.

One thing is for sure: Osho liked to make a lot of noise, as a means of grabbing people’s attention. He wanted as many people to know about him as possible and was skilled at creating media headlines. In the Seventies, for example, he was hailed as ‘the sex guru’ and we, his sannyasins, were living in ‘the free love ashram’ in Pune, India. Glamorous movie stars from Mumbai came to him for advice, western-style therapy groups generated scandalous tales of fighting and orgies, and finally, in 1981, Osho was alleged to have ‘fled’ the country to avoid being arrested for tax evasion.

Our spiritual circus then moved to Oregon, USA. We bought a 120 square-mile cattle ranch, shocked Americans by taking over a local town, built another town on the ranch, and staged festivals with thousands of people. Meanwhile, Osho swiftly accumulated a fleet of costly cars that earned him the title ‘the guru with 93 Rolls Royces’.

In 1985, Osho was arrested, charged with immigration fraud and deported. He travelled the world, but 21 countries refused him entry. He returned to India and outraged a couple of German journalists by laughingly giving a Nazi salute at the end of one of his discourses. He died in 1990 at the age of 58, having claimed that the Reagan Administration had poisoned his body while he was being held in an American jail.

Those were just some of the headlines. I’m not going to tell the whole story here. After all, I wrote a book about it, titled India’s Misfit Mystic, which, I am bold enough to assert, is probably the most comprehensive and entertaining description of those hectic years.

But the story continues, as does the controversy. In 2018, Netflix released a six-part series titled Wild Wild Country documenting Osho’s years in Oregon, focusing primarily on the struggle between the Rajneesh community and the US Government, as well as numerous crimes committed by Osho’s secretary, Ma Anand Sheela, and her close-knit gang of supporters.

Paradoxically, Sheela, who was cast as the main villain in the Netflix series, earned grudging admiration among some viewers for her unrepentant, ‘I don’t give a damn’ attitude and her tough, ballsy interviews.

More recently, a British television channel, ITV, has sparked another controversy by screening a documentary titled Children of the Cult, which relates how underage girls were prematurely initiated into sex by older men, mainly during the years of the Oregon Ranch.

At the time, this was accepted by most sannyasins, including the girls’ parents, as part of the Ranch’s pervasive ‘free love’ scene. But now the perspective has radically shifted. In the light of the #MeToo movement, these girls—now in their fifties—have found their own voices and are publicly sharing their negative experiences and confronting their perpetrators.

As for Osho himself, if he had been merely a con man, then any of these controversies would have provided ample ammunition for attacking his image as a spiritual mystic. But the problem for me, and many others, is that he was, undeniably, the real deal. Through his presence, his discourses, and above all through the energy field surrounding him, we were easily transported into a state of meditation, inner silence and bliss.

Eckhart Tolle has his own name for this inner state. He calls it ‘Space Consciousness’.

Gautam Buddha called it ‘Shunyata’, divine emptiness.

Zen monks called it ‘The Roaring Silence’.

Jesus called it ‘The Peace that Passes All Understanding’.

Osho simply called it ‘No Mind’.

The bottom line goes like this: when you have a direct personal experience of the essential ‘voidness’ that forms the basis of universal reality, and which you can also embrace as your own inner nature, it’s hard to dismiss the guy who acts as a catalyst to enable this experience to happen.

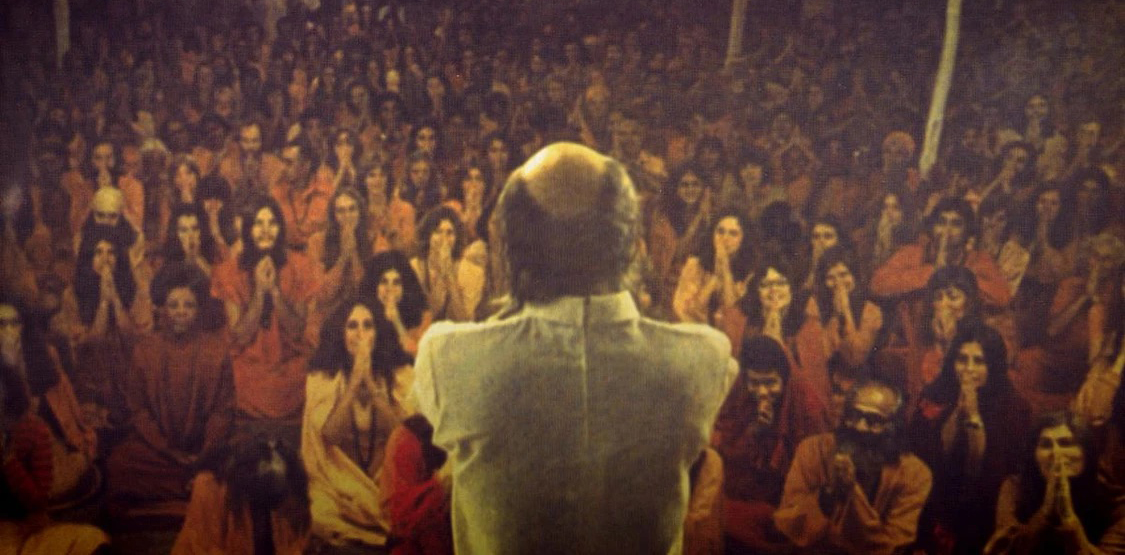

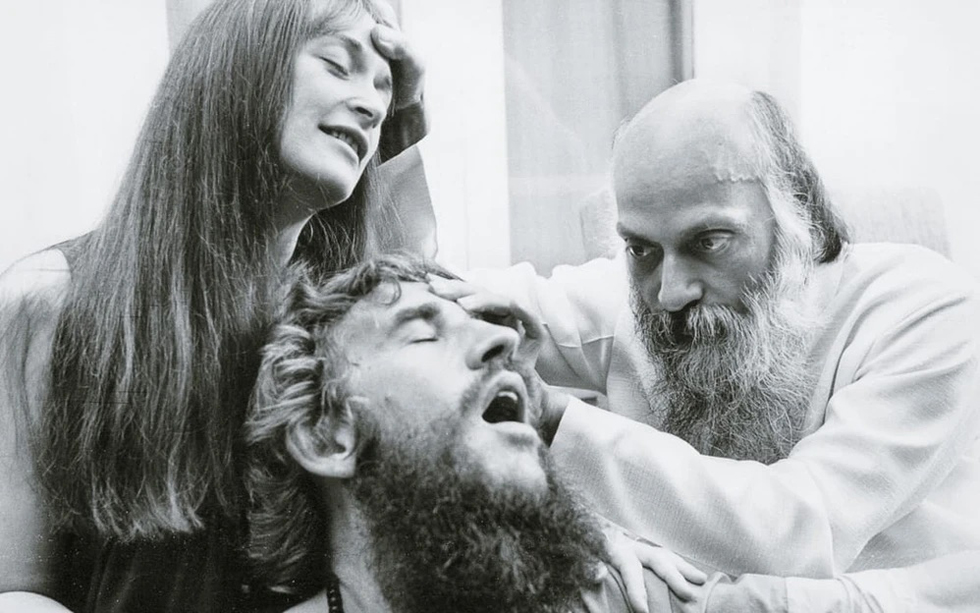

This is what attracted us to Osho. He developed many active meditation methods to help us move inwards on the journey of self-discovery, including his notorious ‘Dynamic Meditation’ that invited us to hyper-ventilate our breathing, scream our heads off, jump up and down like madmen, then suddenly stop all activity and plunge deeply into silence and stillness.

He also made it clear that all philosophy and theology is just rubbish, including religious scriptures and sutras, unless it succeeds in guiding people towards the inner meditative state, which is itself beyond all mental concepts: ‘No words are capable of describing it,’ he explained to us. ‘Every language falsifies the truth. Every expression destroys it.’

© Subhuti Anand Waight, Energy Darshan.

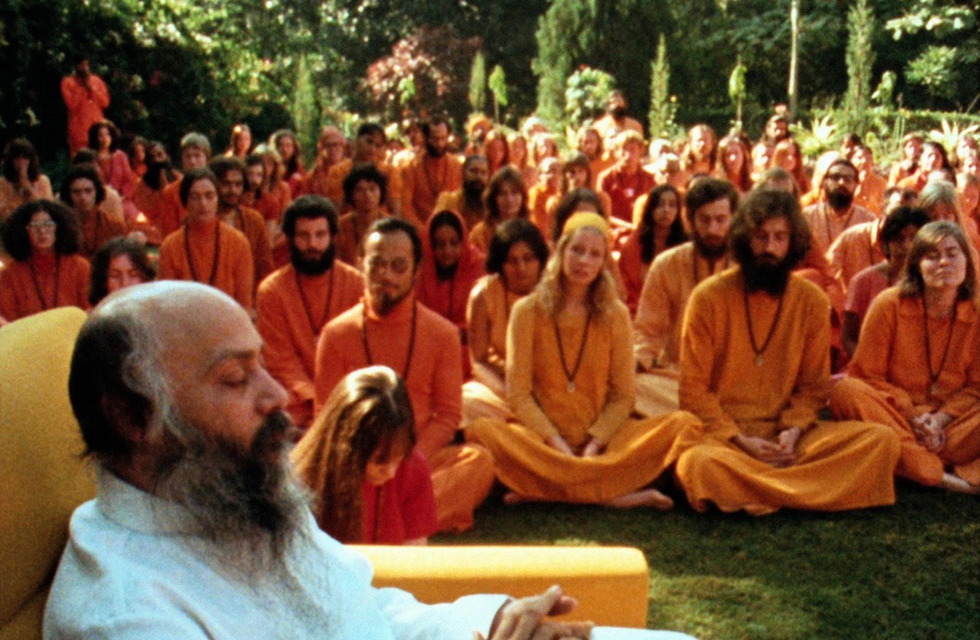

This, then, was Osho’s appeal. Combined with his invitation for us to enthusiastically explore love and sex, together with plenty of opportunities for ecstatic celebration in the form of singing and dancing, he created a powerful magnet that pulled us to Pune in the Seventies. This was also the time when Osho was available for one-on-one meetings and for personally initiating people into sannyas.

In some ways, that elusive fragrance of inner transformation continues today, since people from around the world still find his meditation methods helpful, and feel attracted to Osho meditation centres in India, Europe, the USA and elsewhere.

So, then, what about the controversies? In my book, I have made no effort to turn Osho into a ‘good guy’. I have included everything I can remember about my life with him, including all the controversies and the so-called ‘shadow’ elements.

No doubt, readers who feel that mystics should conform to a certain code of public morality, will continue to insist that Osho was not an enlightened being. But, in doing so, they ignore an inconvenient and uncomfortable truth:

Morality and spirituality have nothing to do with each other.

They don’t share the same bed or exist in the same ballpark.

We have been taught they are one and the same thing, because, over many centuries, this has proved to be a convenient and effective way of controlling people’s behaviour: be good and you’ll go to heaven, be bad and you’ll suffer eternally in hellfire.

Morality is a social phenomenon. It is a kind of inner policeman, inserted into our brains from a very early age, with the intention to help us all get along with each other within a certain social framework, and to refrain from killing our neighbours when they don’t behave as we would like them to.

Spirituality, on the other hand, is the inner quest for the meditative state. No more, no less.

By the way, just to be clear, I am not saying that, because morality is irrelevant, then immoral behaviour is okay. If you want to lie, cheat, rob and steal, that’s up to you, but it won’t achieve much, except to increase your chances of ending up jail, and is unlikely to produce an experience of inner calmness and peace.

Paradoxically, positivity and negativity were both welcomed by Osho. When I joined his community in Pune, in 1977, the mystic invited me to work in his press office. As a former journalist—I was once a political reporter in the British Houses of Parliament—my main job was to respond to any negative news stories about him, which, as you can imagine, kept me pretty busy. The witty sarcasm that I’d cultivated as a commentator on British politics stood me in good stead when ridiculing Osho’s critics, turning their own arguments against them.

It was in the press office that I discovered Osho’s approach to negative publicity. The best example I can think of occurred when a well-known German film actress called Eva Renzi came to the Pune ashram. She had also gained international recognition by starring with Michael Caine in the British spy film, Funeral in Berlin.

Initially, Renzi signed up to participate in a gentle introductory group, whose function was to help newcomers acquire the knack of self-awareness. But, after a short time, she became bored and restless. She asked to be transferred to the Encounter Group, a request that probably should have been denied, since Renzi did not seem to understand the main purpose of this intense process: to dare to go beyond one’s normal attitudes, behaviour and limits.

One of the first challenges in this group was that people were invited to spend the night with another participant who was a stranger to them. Paired off with a 50-year-old Dutchman, Renzi had dinner with the man, but then insisted on returning to her hotel room alone.

The next day in the group she found herself being slapped by the Dutchman, who called her a ‘phony bitch’. According to Renzi, the whole group then turned on her, ripping off her clothes, slapping her and leaving her naked with a bleeding nose. Deeply distressed, she ran out of the ashram and sought help from the German consulate in Mumbai, lodged a complaint with the Pune police, and told her story to DPA, the German international press agency. Her dramatic tale soon appeared on the front page of Bild Zeitung and all over the German media.

Commenting in discourse, Osho said he felt sorry for Eva Renzi, because she had missed a great opportunity. He dismissed her allegations as wildly exaggerated and also saw advantages in this scandalous story: ‘Now it is all over Germany. Everybody knows my name—this is something great—and everybody is asking about me, “Who is this man?”’In the press office, we came to understand Osho’s approach very well. ‘Just create the negative and the positive starts coming. Create the positive and the negative starts coming. They always balance, so never be worried about negative things; it is always like that,’ he told us.

The debate about Osho will never be concluded, because, as we all know, there are no objective criteria for determining who is enlightened and who is not. Religion is an invisible commodity. So is meditation. Idiots can claim to be prophets and masters, and can gather sizeable followings. Authentic mystics can make the same declaration, and might be completely ignored.

However, no one could ignore Osho. Love him or hate him, he had a knack of grabbing headlines, irritating or amusing people, challenging their beliefs and prejudices.

As for myself, I know from personal experience that Osho was an Awakened Being. For 14 years, I was with him, living and working in his presence, in his energy field. Through his function as a door to the Beyond, I tasted the state of inner emptiness and drank the divine wine, melting into the vastness of existence.

These were temporary experiences on my part, triggered by Osho as a catalyst. Each time, after it had happened, I was obliged to return to what one might describe as the ‘normal’ state of human consciousness. And so, my own enlightenment continues to be work in progress. It may happen in this life. It may not.

To say it clearly: my book is an attempt to tell the whole story of Osho: the good, the bad, the bizarre, the beautiful, and the Beyond. An impossible task, for sure, but one that hopefully transcends the mundane world of categorizing him as either a great saint or a ruthless charlatan.

You are most welcome to accompany me on this fascinating journey into the life of India’s most controversial mystic at my website and photo gallery.

Post Notes

- Feature image: © Subhuti Anand Waight, Buddha Hall

- Subhuti Anand Waight’s website and photo gallery

- Rashid Maxwell: A Master for Life

- W. Somerset Maugham: The Saint

- Alan Jacobs: Who Am I?

- Ana Ramana: Hymns to the Beloved

- Upahar: Bright Like a Million Suns

- Ditmar Bollaert: Arunachala Pradakshina

- Jean-Raphael Dedieu: Jnani, The Silent Sage of Arunachala

- Ana Ramana: Hymns to the Beloved

- Paula Marvelly: Rendezvous With Ramana, Part I

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme