Image: Public Domain

Improvisation in life and art

I am a musician. One of the things I love best is to give totally improvised concerts on violin, viola, and electric violin. There is something energizing and challenging about being one-to-one with the audience and creating a piece of work that has both the freshness of the fleeting moment and—when everything is working—the structural tautness and symmetry of a living organism. It can be a remarkable and often moving experience in direct communication.

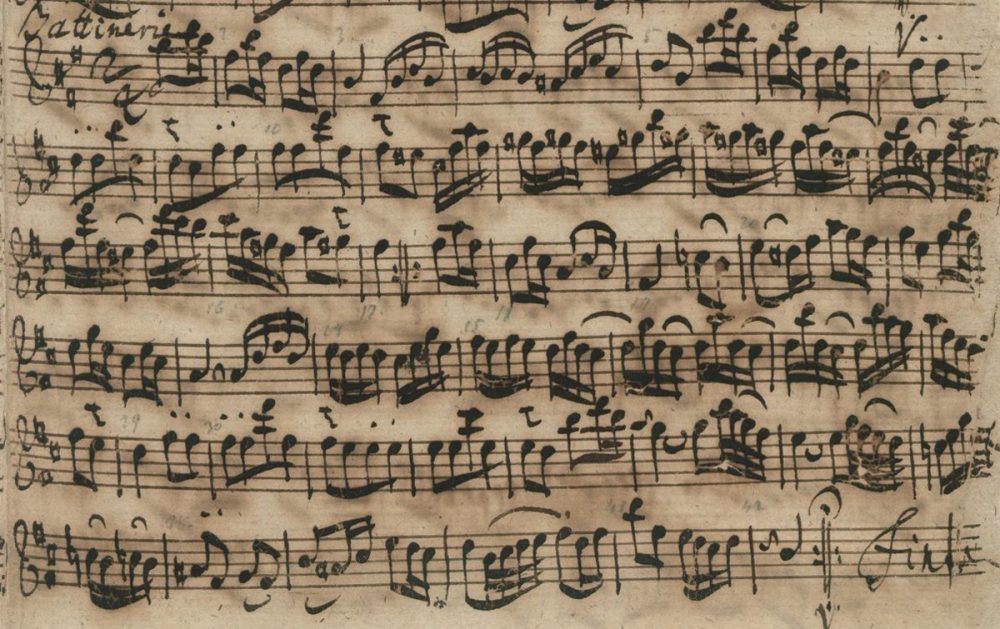

My experience of playing in this way is that ‘I’ am not ‘doing something’; it’s more like following, or taking dictation. This is, of course, a feeling that has been expressed many times by composers, poets, and other artists. There is the story of one of Bach’s pupils asking him, ‘Papa, how do you ever think of so many tunes?’ to which Bach replied, ‘My dear boy, my greatest difficulty is to avoid stepping on them when I get up in the morning.’ And there is the famous example of Michelangelo’s theory of sculpture: the statue is already there in the stone, has been in the stone since the beginning of time, and the sculptor’s job is to see it and release it by carefully scraping away the excess material. William Blake, in a similar vein, writes of ‘melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite, which was hid’.

I HAVE ALREADY written of the uncanny coincidence of reading another of Stephen Nachmanovitch’s books, whereby I was taking a trip to Foyles bookshop on the South Bank in London, deciding to wile away the train journey reading his magnificent The Art of Is, only to discover to my utter amazement that the opening chapter describes a selfsame visit to a bookstore on the South Bank! Free Play, an earlier work published for the first time in the UK by Canongate after its initial publication 34 years ago in the US and abroad, has yielded another synchronistic moment, coming into my life when I needed it most.

Although Stephen Nachmanovitch is predominantly known for being a maestro on violin and viola, Free Play explores improvisation in both daily life and all the creative arts. Elegantly written, each sentence imbued with poetic musicality that only a lifelong apprentice of acoustics can muster, the overarching theme of this exceptional work is an exploration of the vicissitudes and victories of the creative process.

And so, on the threshold of trying my hand at writing fiction, after decades of editing and reviewing the work of others, I have decided it is high time to knuckle down and complete The Novel, which has languished under my bed for nearly a decade, dispelling all perfectionism and procrastination and simply allowing the mysterious business of finishing the task with Free Play as my guide.

Image: © Remedios Varo, 1960

Courtesy Walter Gruen

This book is directed toward people in any field who want to contact and strengthen their own creative powers. Its purpose is to propagate the understanding, joy, responsibility, and peace that come from the full use of the human imagination.

The questions we will delve into concern how intuitive music, or inspiration of any kind, arises within us, how it may be blocked, derailed, or obscured by certain unavoidable facts of life, and how it is finally liberated—how we are finally liberated—to speak or sing, write or paint, with our own authentic voice. Such questions lead us directly into territory where many religions and philosophies, as well as the actual experience of practising artists, seem to converge.

What is the Source we tap into when we create? What did the old poets mean when they talked about the muse? Who is she? Where does the play of imagination come from? When are sounds music? When are patterns and colours art? When are words literature? When is instruction teaching? How do we balance structure and spontaneity, discipline and freedom? How does the passion of the artist’s life get coded into the artwork? How do we as creators of artwork see to it that the original vision and passion that motivate us get accurately portrayed in our moment-to-moment creative activity? How do we as witnesses of artwork decode or release the passion when the artist is gone and we have only the artwork itself before us, to see and listen to, to remember and accept? How does it feel to fall in love with an instrument and an art?

There are many, many books out there that explore creativity and explain how to unleash the inner muse. Somewhat ironically, however, they are often written prescriptively and prosaically, rendering them dull as dishwater. The beauty of Free Play is that it is in itself an exquisite manifestation of the very subject the author is talking about. Drawing on musical anecdotes together with wisdom from the world’s mystical traditions—Western transcendental philosophy, Sufism, Zen Buddhism—it is little wonder that Stephen’s offering has become a literary classic.

For example, one of the main leitmotifs of the text, regarding improvisation and surrender, is taken from a Japanese folk story about a master musician, who discovers in China a newly invented flute, brings it home and gives concerts all around Japan. One evening, after playing for a community of musicians and music lovers, his flute performance is met with a prolonged silence, until the voice of the oldest man is heard from the back of the room: “Like a god!”

The master musician grants a request to take on a pupil, who is given the singular task of playing a simple tune. The student practises the melody for endless hours, day after day, week after week, with no respite and yet all his master can say of his efforts is “something lacking”. The pupil begs his master to change the tune but he repeatedly declines. Inevitably, the relentless “something lacking” erodes the student’s confidence, rendering him full of despondency with the result that he finally collects up his things and leaves. Returning to his homeland, feeling ashamed at his apparent failure, he retires to the countryside for a quiet life, occasionally taking in students to supplement his living.

One morning, there is a knock on the door. It is the oldest past master from his town inviting him to play at a concert. Reluctantly, the former student picks up his flute and goes with them to the performance. Now he realizes that he has nothing to gain and nothing to lose. He sits down and plays the same tune that he played so many times for his former teacher. When he finishes, there is silence for a long moment. Then the voice of the oldest man is heard, speaking softly from the back of the room: “Like a god!”

Image: Public Domain

Beethoven at the age of thirty-two realized that he would never recover his hearing, and even worse, foresaw the loneliness and emotional isolation that was in store for him. He wrote his despairing, premature will, the Heiligenstadt Testament, in those same summer weeks as he wrote the Second Symphony, that incomparable study of light, air and happiness. He was later to write of this time: ‘If I had not read somewhere that a man may not voluntarily part with his life so long as a good deed remains for him to perform, I should long ago have been no more.’ The Eroica Symphony, one of the revolutionary conceptual and emotional leaps in the history of art, arose from Beethoven’s synthesis of the vastly conflicting states of mind that were forced upon him at this time. Beethoven is so often described by his contemporaries as dreadfully unfortunate, misanthropic, alternately resigned to and defiant of fate. Yet it is precisely because he chose the path of surrender, of despair transcended, that Beethoven, this wild man, this deaf man, lives on among the greatest poets of joy the world has ever known.

There is nothing that can stop the Creative. If life is full of joy, joy feeds the creative process. If life is full of grief, grief feeds the creative process. Examples of jail art abound, the most famous of which is Don Quixote. e. e. cummings wrote the enormous room while incarcerated in a dirty, crowded French jail during World War I. Olivier Messiaen composed Quartet for the End of Time, one of the great accomplishments of twentieth-century music, while in a Nazi concentration camp. Messiaen sat in Stalag VIII in Silesia in the bitter winter of 1941 and created eight movements of, in his words at the time ‘unfailing light, of unalterable peace’. We have seen again and again how immense can be the power of limits, the power of circumstance, the power of life’s pull in generating original breakthroughs of mind and heart, spirt and matter. It’s wonderful to retire to a mountaintop and paint pretty pictures. But more wonderful and more challenging still is for the artist to sit right in the midst of the karmic struggle …

So often we hope for improved circumstances—better finances, more time to ourselves, an inspirational love affair—to assist us in getting on with our work. And yet, in the history of the creative arts, it was the very fact of being reduced to the humblest of existence that artistry was able to flow. It is because of poverty or illness, confinement with others, being left without a single friend in the entire world, that the human spirit of resourcefulness, paradoxically, is able to arise forth.

Only then, when we have utterly surrendered ourselves to the visionary intelligence beyond rational thought and life’s (even most hideous) conditions, having nothing to gain or lose just like the Japanese flautist, can we muster the disposition to accomplish our creative dreams. Renouncing the inner editor and critic, together with our fallacious beliefs surrounding self-worth and lack of ability, can the magic, the lila, start to play. A “Yes! Yes! Yes!” to the divine creativity, as in Molly Bloom’s life-affirming mantra at the end of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Indeed, Stephen Nachmanovitch is living proof of the improvisational process of which he so compelling writes. The past six months alone have seen both the publication of Free Play as well as the release of his latest album, Music from Before the Beginning, which explores a fascination with “organic evolution as a continuous unfolding of communication, in layers and levels that interweave and intertwine in shapes we cannot describe but can experience”. Listening to the haunting bricolage of strings, synth and woodwinds, so exquisitely extemporized, I am left with the simple reaction of whispering to myself, “Like a god!”

Post Notes

- Stephen Nachmanovitch’s website

- Stephen Nachmanovitch: The Art of Is

- Stephen Nachmanovitch: Taming the Mind Ox

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Eric Nicholson: William Blake’s Vision of the Book of Job

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- John Cage: Silence

- Arvo Pärt: Silentium

- John Tavener: Towards Silence

- John Adams: The Dharma at Big Sur

- Antony Gormley: Sculpted Space Within and Without

- Mark Rothko: The Artist’s Reality