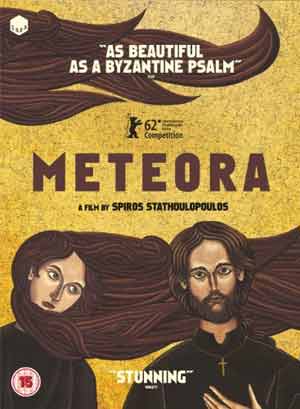

Spiros Stathoulopoulo, Meteora

The enduring power of eternal love

“Yes, happiness and grace will accompany me every day of my life.

And I will dwell in the house of the Lord until the end of my days.

The Lord is my shepherd, I lack nothing.”

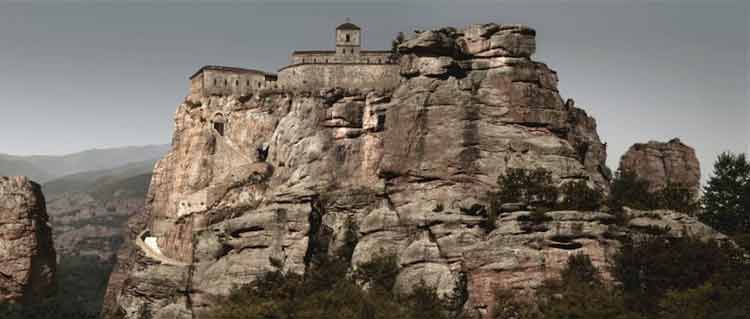

SPIROS STATHOULOPOULOS’ METEORA is the simple and yet exquisitely beautiful tale of the trials and tribulations of the human heart. Blending animation with moving image, the film explores the forbidden relationship between a Greek monk, Theodoros, and a Russian nun, Urania, set amidst the stunning backdrop of the monastery complex, Metéora, which translates as “floating” or “suspended in the air” and symbolizes its physical isolation from the world of man and its spiritual closeness to the realm of God.

Photograph: © 2017, Kairos Film

Reminiscent to the Italian arthouse film, Le Quattro Volte, in terms of its elegance and pacing, Meteora is a love letter to art, faith and life itself, exemplified both by its sumptuous montage and the eternal conundrum of whether or not it is sinful to partake of passionate enjoyment of the flesh.

Oscillating between documentary-style footage of daily peasant life and majestic photographic vistas of the Thessalyian rock pinnacles subsumed in sunlight, mist and shadows, Spiros Stathoulopoulos’ cinematic project is a visually stunning masterpiece.

Photograph: © 2017, Kairos Film

The film opens with an understated scene in which the two protagonists exchange prayer beads and bless each other at the foot of their respective cenobia—the Monastery of the Holy Trinity and the Agios Stefano Convent. Their shyness and yet apparent mutual attraction are enthralling and already we are hooked by our fascination with that most potent and powerful human feeling of all: sexual desire.

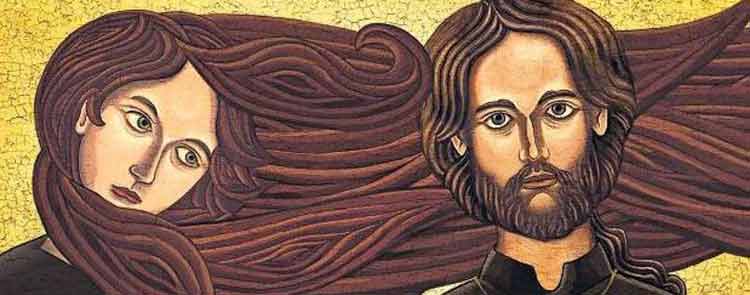

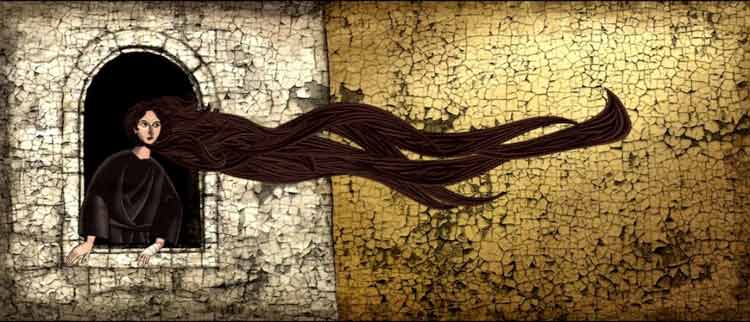

We then witness them partaking of a picnic, making small talk and nibbling on meat and bread, with occasional slugs of wine. These are basic human acts and yet they are loaded with emotional nuance. Theodoros wants to know what is the colour of Urania’s hair but she will not tell him. Finally, the tension is too much and he embraces her—she protests but then yields to his advances. He pushes back her bandeau and her auburn hair haemorrhages into his hands.

Photograph: © 2017, Kairos Film

Throughout the film, the irony is not wasted as the two lovers communicate by use of the reflected light from the religious icons that they ordinarily kiss and pray before, which darts and dances upon the walls of their hermetic cells.

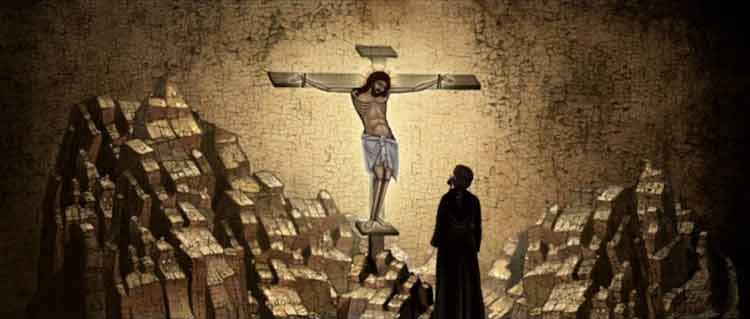

As their longing for each other increases, seductive and sumptuous Byzantine-style anime sequences in the manner of Greek iconography pictorially represent the psychological states of the protagonists, culminating in surrealistic explorations of the Christian Orthodox liturgy, Greek mythology and the depths of the human psyche.

Photograph: © 2017, Kairos Film

In a particularly entrancing scene, Theodoros’ avatar embodies Theseus, the mythological Greek king of Athens, and enters into an underground labyrinth carrying a ball of wool to help him find his way back out. But he loses the wool and his flame torch is extinguished by a sudden draft and he is lost and alone and afraid.

Then in the darkness, he beholds Christ tied to the cross. Theodoros/Theseus nails Jesus’ hands into the wood with stakes, whereupon his fingers spew rivers of baptismal blood. Carried along by the hematic waves, evocative of similar themes painted by Carl Jung is his magnum opus, The Red Book, Theodoros is washed out of the labyrinth and reunited with Urania, drenched in the love of the Holy Son.

Photograph: © 2017, Kairos Film

Indeed, watching Meteora is akin to participating in our own sacred experience whereby we are able to empathize with the power of carnal passion, challenging our own beliefs in relation to religious doctrine, sexual desire and the supposition that human intercourse is a gateway to embracing the divine.

The inevitable climax of their physical yearning in a secluded silent cave, beautifully framed by penetrating shafts of sunlight, consummates their relationship, releasing them both of the guilt and shame they have been carrying up until this point. No doubt some devout Christians will be appalled by Spiros Stathoulopoulos’ message; he has indeed led us into temptation and yet at the end of the day it is only our own conscience that will decide whether the film is morally sound or not.

Photograph: © 2017, Kairos Film

Probably the most compelling component of Meteora is the soundtrack and musical score. The minimal dialogue is compensated by the hypnotic pulsation of cicadas sawing in the grass, goats bleating in the ravines and pastures, monastery bells chiming in the offices of the day.

This is poignantly counterpointed by the Gregorian chants of Pérotin, namely Viderunt Omnes and Beata Viscera, both acoustically in harmony with the unfolding cinematographical elements and elevating the film into an ethereal gem.

Photograph: © 2017, Kairos Film

The dénouement of Meteora is ambiguous as all great films should be. Will Theodoros and Urania return to their respective monasteries or embark on a new life together well beyond the confines of religious rite? Who knows and, in one sense, this is not, ultimately, the point.

The epilogue, mirroring the prologue, focuses on a Byzantine triptych detailing scenes from the lovers’ journey into “sin”. By encapsulating their erotic tryst within the confines of the frame of a painting, perhaps we are able to judge our protagonists a little less harshly, understanding that our lives are works of art in progress steeped in eternal love, not acts of heartless discipline set in stone.

“Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil, for you are with me.”

Post Notes

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- Xavier Beauvois: Of Gods and Men

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- Michelangelo Frammartino: Le Quattro Volte

- Kon Markogiannis: Memento Immortality

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates

- Gospel of Mary Magdalene

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora