Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

The art of stillness

“Most of all, the mind must be withdrawn from external interests into itself. Let it have confidence in itself, rejoice in itself, let it admire its own things, let it retire as far as possible from the things of others and devote itself to itself, let it not feel losses, let it interpret kindly even adversities.”

THERE IS A sophistication and elegance about the way in which the Greek and Roman philosophers, like the Taoist sages, approach the nature of the mind. Concise, practical and yet utterly insightful, literature of the Greats is just as pertinent today as it was two millennia ago.

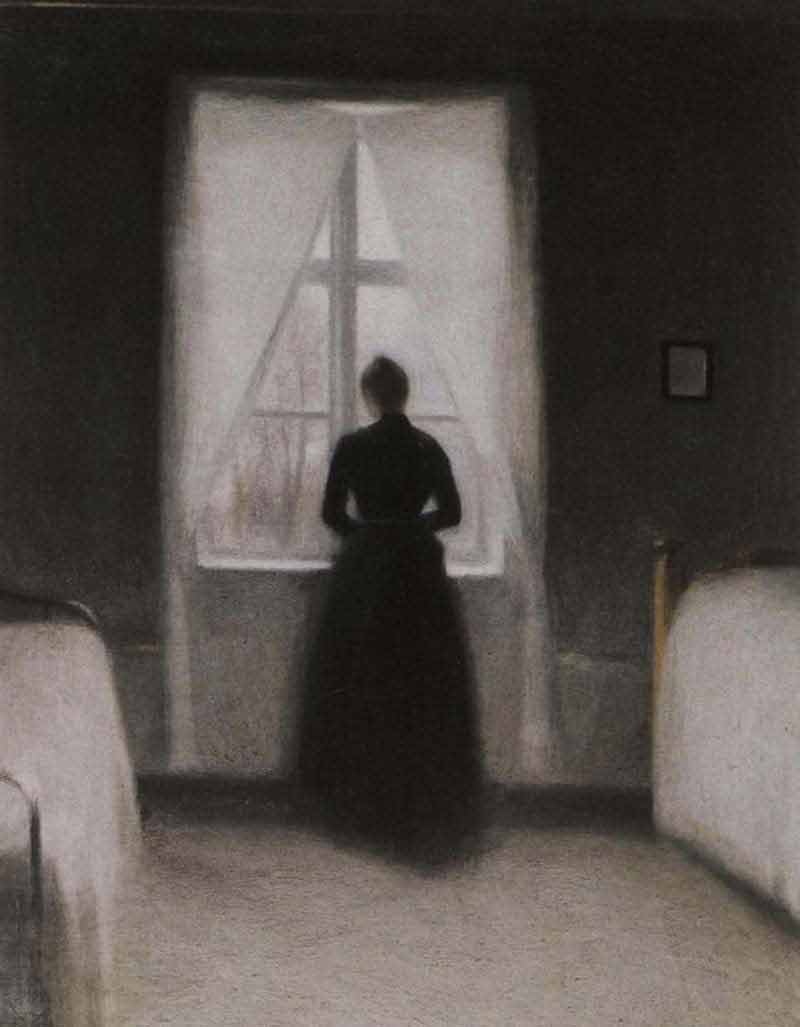

Interior With Woman at Piano, Strandgade 30.

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

SERENUS: When I made examination of myself, it became evident, Seneca, that some of my vices are uncovered and displayed so openly that I can put my hand upon them, some are more hidden and lurk in a corner, some are not always present but recur at intervals; and I should say that the last are by far the most troublesome, being like roving enemies that spring upon one when the opportunity offers, and allow one neither to be ready as in war, nor to be off guard as in peace.

Nevertheless the state in which I find myself most of all—for why should I not admit the truth to you as to a physician?—is that I have neither been honestly set free from the things that I hated and feared, nor, on the other hand, am I in bondage to them; while the condition in which I am placed is not the worst, yet I am complaining and fretful—I am neither sick nor well. There is no need for you to say that all the virtues are weakly at the beginning, that firmness and strength are added by time. I am well aware also that the virtues that struggle for outward show, I mean for position and the fame of eloquence and all that comes under the verdict of others, do grow stronger as time passes—both those that provide real strength and those that trick us out with a sort of dye with a view to pleasing, must wait long years until gradually length of time develops colour—but I greatly fear that habit, which brings stability to most things, may cause this fault of mine to become more deeply implanted. Of things evil as well as good long intercourse induces love.

The nature of this weakness of mind that halts between two things and inclines strongly neither to the right nor to the wrong, I cannot show you so well all at once as a part at a time; I shall tell you what befalls me—you will find a name for my malady.

Written by Lucius Annaeus Seneca (also known as Seneca the Younger) (4 BCE–65 CE), On Tranquillity of Mind (De Tranquillitate Animi) is a Latin dialogue concerning the state of mind of Seneca’s friend, Serenus, and how to cure him of the perpetual state of anxiety he is experiencing, together with a pervading disgust with the overall nature of life.

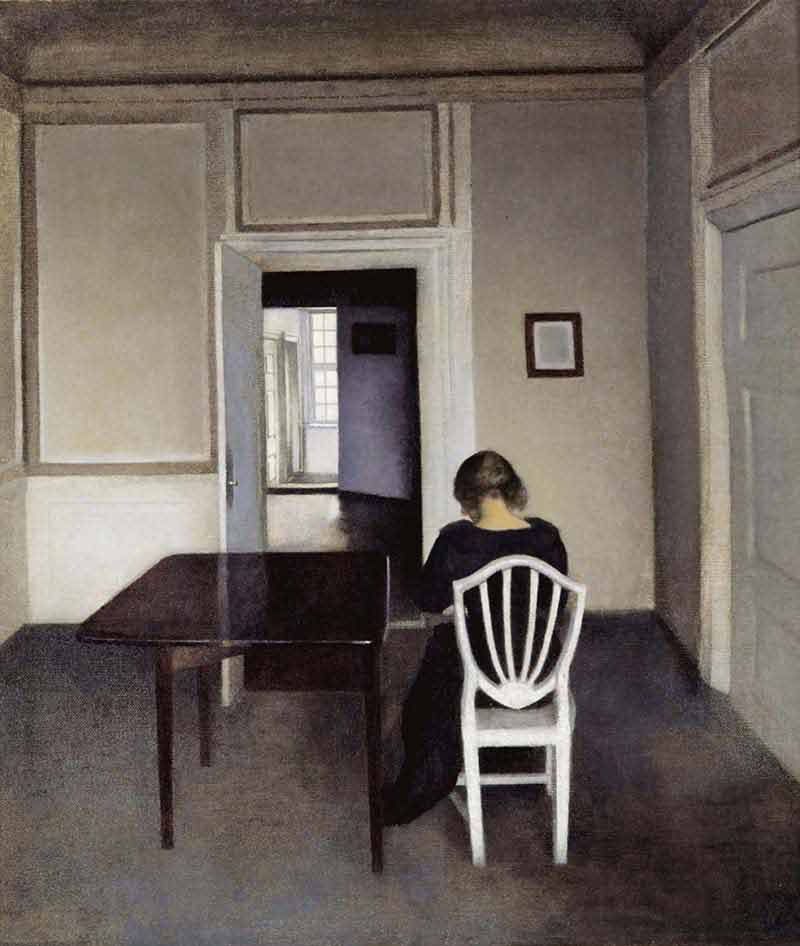

Interior From Strandgade With Sunlight on the Floor.

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

Not to indulge longer in details, I am in all things attended by this weakness of good intention. In fact I fear that I am gradually losing ground, or, what causes me even more worry, that I am hanging like one who is always on the verge of falling, and that perhaps I am in a more serious condition than I myself perceive; for we take a favourable view of our private matters, and partiality always hampers our judgement.

I fancy that many men would have arrived at wisdom if they had not fancied that they had already arrived, if they had not dissembled about certain traits in their character and passed by others with their eyes shut. For there is no reason for you to suppose that the adulation of other people is more ruinous to us than our own. Who dares to tell himself the truth? Who, though he is surrounded by a horde of applauding sycophants, is not for all that his own greatest flatterer? I beg you, therefore, if you have any remedy by which you could stop this fluctuation of mine, to deem me worthy of being indebted to you for tranquillity. I know that these mental disturbances of mine are not dangerous and give no promise of a storm; to express what I complain of in apt metaphor, I am distressed, not by a tempest, but by sea sickness.

Do you, then, take from me this trouble, whatever it be, and rush to the rescue of one who is struggling in full sight of land.

Published alongside On the Shortness of Life as part of Penguin Books excellent Great Ideas series, On Tranquillity of Mind is one of the most profound and thoughtful dialogues I have ever read on the tempestuous nature of the mental realm and a means to finding inner salvage.

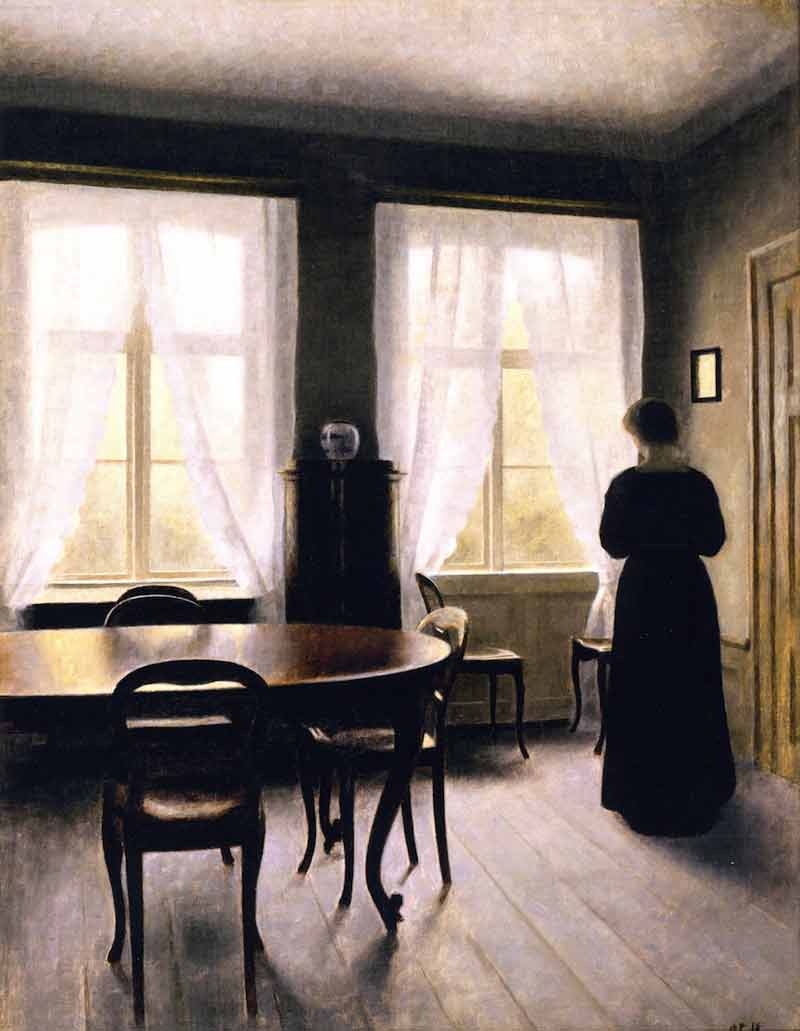

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

SENECA: In truth, Serenus, I have for a long time been silently asking myself to what I should liken such a condition of mind, and I can find nothing that so closely approaches it as the state of those who, after being released from a long and serious illness, are sometimes touched with fits of fever and slight disorders, and, freed from the last traces of them, are nevertheless disquieted with mistrust, and, though now quite well, stretch out their wrist to a physician and complain unjustly of any trace of heat in their body. It is not, Serenus, that these are not quite well in body, but that they are not quite used to being well; just as even a tranquil sea will show some ripple, particularly when it has just subsided after a storm. What you need, therefore, is not any of those harsher measures which we have already left behind, the necessity of opposing yourself at this point, of being angry with yourself at that, of sternly urging yourself on at another, but that which comes last—confidence in yourself and the belief that you are on the right path, and have not been led astray by the many cross-tracks of those who are roaming in every direction, some of whom are wandering very near the path itself. But what you desire is something great and supreme and very near to being a god—to be unshaken.

This abiding stability of mind the Greeks call euthyimia, “well-being of the soul”, on which there is an excellent treatise by Democritus; I call it tranquillity. For there is no need to imitate and reproduce words in their Greek shape; the thing itself, which is under discussion, must be designated by some name which ought to have, not the form, but the force, of the Greek term. What we are seeking, therefore, is how the mind may always pursue a steady and favourable course, may be well-disposed towards itself, and may view its condition with joy, and suffer no interruption of this joy, but may abide in a peaceful state, being never uplifted nor ever cast down. This will be “tranquillity”. Let us seek in a general way how it may be obtained; then from the universal remedy you will appropriate as much as you like. Meanwhile we must drag forth into the light the whole of the infirmity, and each one will then recognize his own share of it; at the same time you will understand how much less trouble you have with your self-depreciation than those who, fettered to some showy declaration and struggling beneath the burden of some grand title, are held more by shame than by desire to the pretence they are making.

Seneca was a Roman senator and political advisor to Emperor Nero, whom he was accused of being complicit in a plot to assassinate. Like Socrates before him, Seneca was forced to take his own life, which he did with dignity and equanimity, surrounded by his closest friends, becoming the very embodiment of the wisdom he imparted and the detachment he steadfastly maintained.

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

All are in the same case, both those, on the one hand, who are plagued with fickleness and boredom and a continual shifting of purpose, and those, on the other other, who loll and yawn. Add also those who, just like the wretches who find it hard to sleep, change their position and settle first in one way and then in another, until finally they find rest through weariness. By repeatedly altering the condition of their life they are at last left in that in which, not the dislike of making a change, but old age, that shrinks from novelty, has caught them. And add also those who by fault, not of firmness of character, but of inertia, are not fickle enough, and live, not as they wish, but as they have begun. The characteristics of the malady are countless in number, but it has only one effect—to be dissatisfied with oneself. This springs from a lack of mental poise and from timid or unfulfilled desires, when men either do not dare, or do not attain, as much as they desire, and become entirely dependent upon hope; such men are always unstable and changeable, as must necessarily be the fate of those who live in suspense.

They strive to attain their prayers by every means, they teach and force themselves to do dishonourable and difficult things, and, when their effort is without reward, they are tortured by the fruitless disgrace and grieve, not because they wished for what was wrong, but because they wished in vain. Then regret for what they have begun lays hold upon them, and the fear of beginning again, and then creeps in the agitation of a mind which can find no issue, because they can neither rule nor obey their desires, and the hesitancy of a life which fails to find its way clear, and then the dullness of a soul that lies torpid amid abandoned hopes. And all these tendencies are aggravated when from hatred of their laborious ill-success men have taken refuge in leisure and in solitary studies, which are unendurable to a mind that is intent upon public affairs, desirous of action, and naturally restless, because assuredly it has too few resources within itself; when, therefore, the pleasures have been withdrawn which business itself affords to those who are busily engaged, the mind cannot endure home, solitude, and the walls of a room, and sees with dislike that it has been left to itself.

From this comes that boredom and dissatisfaction and the vacillation of a mind that nowhere finds rest, and the sad and languid endurance of one’s leisure; especially when one is ashamed to confess the real causes of this condition and bashfulness drives its tortures inward; the desires pent up within narrow bounds, from which there is no escape, strangle one another. Thence comes mourning and melancholy and the thousand waverings of an unsettled mind, which its aspirations hold in suspense and then disappointment renders melancholy. Thence comes that feeling which makes men loathe their own leisure and complain that they themselves have nothing to be busy with; thence too the bitterest jealousy of the advancements of others. For their unhappy sloth fosters envy, and, because they could not succeed themselves, they wish every one else to be ruined; then from this aversion to the progress of others and despair of their own mind becomes incensed against Fortune, and complains of the times, and retreats into corners and broods over its trouble until it becomes weary and sick of itself.

Seneca was one of the main exponents of the school of Stoicism, which teaches that the highest good in life is the pursuit of the four cardinal virtues, namely wisdom, temperance, justice and courage. The aim of one’s existence, therefore, should be the recognition that anything that comes under the agency of the mind—values, desires, judgements—is always under our control and thus subject to scrutiny and adjustment. And thus, the whole passage of one’s voyage through the mortal realm must be to steer oneself toward a safe harbour far removed from wild terrain and blustery seas.

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

For it is the nature of the human mind to be active and prone to movement. Welcome to it is every opportunity for excitement and distraction, and still more welcome to all those worst natures which willingly wear themselves out in being employed. Just as there are some sores which crave the hands that will hurt them and rejoice to be touched, and as a foul itch of the body delights in whatever scratches, exactly so, I would say, do these minds upon which, so to speak, desires have broken out like wicked sores find pleasure in toil and vexation. For there are certain things that delight our body also while causing it a sort of pain, as turning over and changing a side that is not yet tired and taking one position after another to get cool. Homer’s hero Achilles is like that—lying now on his face, now on his back, placing himself in various attitudes, and, just as sick men do, enduring nothing very long and using changes as remedies.

Hence men undertake wide-ranging travel, and wander over remote shores, and their fickleness, always discontented with the present, gives proof of itself now on land and now on sea. ‘Now let us head for Campania,’ they say. And now when soft living palls, ‘Let us see the wild parts,’ they say, ‘let us hunt out the passes of Bruttium and Lucania.’ And yet amid that wilderness something is missing—something pleasant wherein their pampered eyes may find relief from the lasting squalor of those rugged regions: ‘Let us head for Tarentum with its famous harbour and its mild winter climate, and a territory rich enough to have a horde of people even in antiquity.’ Too long have their ears missed the shouts and the din; it delights them by now even to enjoy human blood: ‘Let us now turn our course toward the city.’ They undertake one journey after another and change spectacle for spectacle. As Lucretius says: ‘Thus ever from himself doth each man flee.’

But what does he gain if he does not escape from himself? He ever follows himself and weighs upon himself as his own most burdensome companion. And so we ought to understand that what we struggle with is the fault, not of the places, but of ourselves; when there is need of endurance, we are weak, and we cannot bear toil or pleasure or ourselves or anything very long. It is this that has driven some men to death, because by often altering their purpose they were always brought back to the same things and had left themselves no room for anything new. They began to be sick of life and the world itself, and from the self-indulgences that wasted them was born the thought: ‘How long shall I endure the same things?’

How long indeed. What I love about Seneca is the way in which he is able to articulate and analyse the subtlest of thought formation and nuance of mental state. Moreover, his ability to put his finger on the root of the problem—a deep dissatisfaction with our own selves caused by the restlessness of the mind—to be utterly enlightening and astute. I am truly filled with wonder that life in antiquity was no different to our modern age.

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

And so we ought to adopt a lighter view of things, and put up with them in an indulgent spirit; it is more human to laugh at life than to lament over it. Add, too, that he deserves better of the human race also who laughs at it than he who bemoans it; for the one allows it some measure of good hope, while the other foolishly weeps over things that he despairs of seeing corrected.

And, considering everything, he shows a greater mind who does not restrain his laughter than he who does not restrain his tears, since the laugher gives expression to the mildest of the emotions, and deems that there is nothing important, nothing serious, nor wretched either, in the whole outfit of life …

And this, too, affords no small occasion for anxieties—if you are bent on assuming a pose and never reveal yourself to anyone frankly, in the fashion of many who live a false life that is all made up for show; for it is torturous to be constantly watching oneself and be fearful of being caught out of our usual role. And we are never free from concern if we think that every time anyone looks at us he is always taking our measure; for many things happen that strip off our pretence against our will, and, though all this attention to self is successful, yet the life of those who live under a mask cannot be happy and without anxiety. But how much pleasure there is in simplicity that is pure, in itself unadorned, and veils no part of its character! Yet even such a life as this does run some risk of scorn, if everything lies open to everybody; for there are those who disdain whatever has become too familiar. But neither does virtue run any risk of being despised when she is brought close to the eyes, and it is better to be scorned by reason of simplicity than tortured by perpetual pretence. Yet we should employ moderation in the matter; there is much difference between living naturally and living carelessly.

Moreover, we ought to retire into ourselves very often; for intercourse with those of dissimilar natures disturbs our settled calm, and rouses the passions anew, and aggravates any weakness in the mind that has not been thoroughly healed.

Akin to all the great philosophers past and present, West and East, advocating a thorough examination of the interior life, we feel equally nourished by Seneca’s insightful discourse, rendering our distracted and excitable being replete with reflective nutriment. Furthermore, unlike the ubiquitous “quote bites” pedalled on social media with their veneer of positive thinking, Seneca’s sagacious essay lingers long after the final sentence, bringing in its wake a deep contentment and a state of inner peace.