Photograph: © Richard Heys

Canvases of the soul

“In the realization of a finished work,

I aim to recover mystery and in this world of the known,

I work standing before the unknown.”

IN HIS SEMINAL work, Mount Analogue, an allegorical novel about man’s journey along the spiritual path, French novelist, René Daumal, likens a mountain to the bridge between the profane and the sacred:

… in the mythic tradition, the Mountain is the bond between Earth and Sky. Its solitary summit reaches the sphere of eternity and its base spreads out in manifold foothills into the world of mortals. It is the way by which man can raise himself to the divine and by which the divine reveals itself to man.

In this month’s guest post for The Culturium, British artist, Richard Heys, takes a similar lead from the vertiginous ridges and alpine ranges of his visual imagination to explore the way in which the abstract sublime can deliver man from his limited self and unlock the mystery of life.

Photograph: © Richard Heys

I currently live in Sussex on the fringes of the Ashdown Forest and work from a fabulous studio at Emerson College. I have been a contributing teacher at Emerson since 2005, teaching in the art department. The full-time Visual Arts course is not currently running and when the studios in which I used to teach came up for rent, I was keen to embrace the space in order to create larger works. I live a mile across the valley from Emerson and often walk to and from the studio through the fields.

In my practice, I strive to bring presence into painting, to open up a soul space allowing the viewer to breathe with the artwork. For me, a painting must have countenance—a spiritual presence—so that the artwork may live on in the mind of the viewer, free to evolve over time. Aiming for mystery in this world of the known, I create standing before the unknown.

Photograph: © Richard Heys

What set me on this journey was discovering Ian McKeever’s Temple Painting at the Royal Academy in 2007. I couldn’t understand how the piece came off the wall to greet me. I have, since that moment, wrestled with the issue of how to create this presence. These days I have a deeper appreciation of how pure colour can project and recede from the picture plane and this is informed by the “frontality” of the icon tradition, brought into the Abstract Sublime by Mark Rothko.

In 2013, I was excited to visit the Gerhard Richter Retrospective at the Tate Modern and was surprised to discover that his work made me feel unwell. Seeing image after image of grey or smeared and scraped colours left me without breath. At that very moment, I decided to explore printmaking equipment and make some paintings that glowed with transparent breathing colour.

I remember time spent in the printmaking department whilst studying for my Fine Art degree. There I learnt so much about process and light and darkness through engaging with various print techniques and pushing these to see how far I could go. This exploration is still ongoing. In my practice, I work with printmaking equipment, bespoke tools and squeegees, knives, silicon blades and brushes. I work to remould inner spaces, to invite attention to and engagement with surface and image, surface and depth, outer picture and inner soul-space. I aim to create, borrowing a phrase, “the painting as a doorway”.

Photograph: © Richard Heys

I’m trying to get to a place when I’m painting where I’m not self-consciously working, so that I can empty myself out and then if I take something that is under way and radically alter it, I can create something startlingly new. I may have been working for four or five weeks, or four or five hours, and then I take this painting in its beginning stages, change it and something new arrives. When this is happening, it’s not a struggle, I know exactly what to do—make a new gesture, add a different colour, draw in the squeegee from the side, turn the canvas—a new dynamic appears that I had not foreseen and could not consciously have created. As the American poet, Albert Huffstickler, wrote:

There’s always

that edge of doubt.

Trust it.

That’s where the new things come from.

—Albert Huffstickler, “The Edge of Doubt”

Photograph: © Richard Heys

“Onward movement is itself a return”

—Tim Ingold and Jo Lee

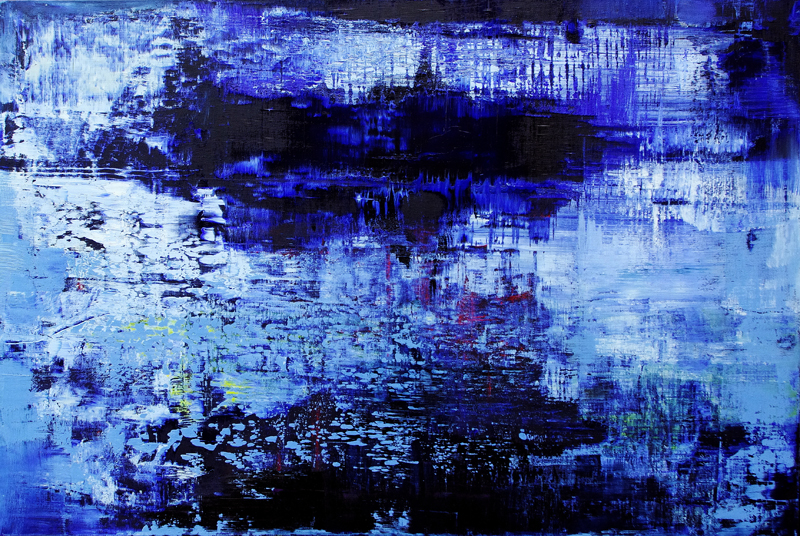

There’s something very special that happened after my father died. I was trying to find my way forward into painting. I realized that I had to go back and pull out canvases from my 20s, alter and completely remake them. It was as if the world had been unmade with the loss of my father. A great indigo curtain had clamped down, chasing away colour—I began working to reimagine the world.

I think that, as my doctor said to me recently, the finest creativity comes from our deepest vulnerability. When you are standing within this vulnerability, you are in an unknowing place. Only when you can remain in this place can you move towards a new understanding, something can speak into that place as you are not in your normal knowing mind, which may stop you from seeing. It’s really very important to step out of your habits. They can be very deadening, very certain, very sure and quite deadly. As soon as you don’t know, you doubt, you wonder, you are questioning and then painting becomes like a revelation. There’s an incredible poignancy to working on a ruined painting—destroy, cover, take the beauty away and then something deeper can emerge. As the painter, Per Kirkeby, said, “We work standing amongst ruins.”

I have faith in painting because of the things that continue to arise. A beauty can arise, which is beyond your conscious grasp. It’s not planned, there’s no formula to get there, it’s a purely serendipitous happening and it can be just what you need. This is meaningful chance or synchronicity; the pull of surface, the flow of paint, the pressure on a squeegee—it is en-souled activity, this process of making. As Odilon Redon, the French Symbolist artist, said, “Materials have their own secrets to reveal: they have their own genius: it is through them that the oracle speaks.”

And only when you let go of illustrating, do you step into that free space—not illustrating your ideas or someone else’s. Not engaged in copying—you are fully engaged in the activity of painting with all your skill—you are right on the edge of it and something higher can work through that. Colour is deeply mysterious, it has a weight and substance, has its own truth beyond our uses, fleeting fashions and cultural misappropriations. Australian anthropologist, Michael Taussig, explores colour as “polymorphous magical substance” in his book, What Color is the Sacred? We have to keep questioning, doubting we ever have the final word.

Photograph: © Richard Heys

It’s hard to describe the genesis of the Holy Mountain series, as paintings come to fruition in their own time and have their own logic and rhythm. Three of these paintings I started when I was 28 years old. For example, Sophia was originally a transcription of Odilon Redon’s Beatrice, a piece I made 27 years ago. In 1993, I had a significant imaginative experience during meditation, in which I found myself on a desert plane looking off into the distance towards a range of mountains when a naked man (my swarthy self) ran past me from the right. He was struggling and fighting as he went, attempting to turn another way. But he was guided by a huge and gracious swan, which sat calmly and serenely on the top of his head leading him toward the mountains, while he desperately struggled to avoid them, wanting no part in reaching them and denying this inevitability.

From time to time, these mountains began to appear in my work. So I would suddenly see, when making a painting, the form of a mountain appear. I have several pieces of art that float in the studio for many months or even years before I know how to complete them or what they may become. They come back onto my easel time and time again. After the loss of my father and after his funeral when I came back to the studio, I realized that I couldn’t carry on in the same vein. I needed to make significant changes. So I went to my storage area and pulled out many canvases, which for one reason or another had been abandoned or left incomplete, but which were still significant for me. I took them to the studio, cleaned them and reworked them, led by a strong urge, and more “mountains” appeared!

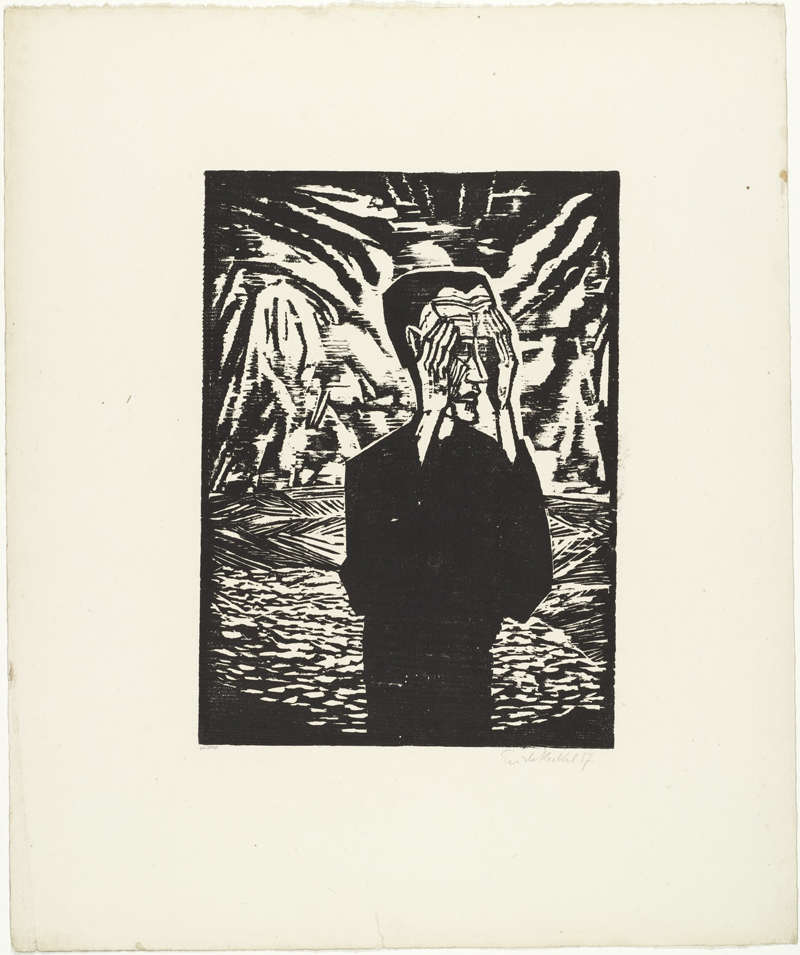

Photograph: © Erich Heckel

When I visited the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart in July 2018, I visited an exhibition of works from the Brucke artists, in which was a woodcut by Erich Heckel, Man in the Plain (1917). This small woodcut resonated so strongly with me—the man in despair with his hands to his head seeming lost, with the distant mountains behind him, chimed with my imaginative experience. As I have said, it is very difficult to describe all that stands behind a painting, from the standpoint of the conscious mind, as paintings are, in a way, their own thinking. But they are also how we make sense of life. British author, Jeannette Winterson, says that art objects are there to carry what we can’t bear and the American artist, Leigh Hyams, describes in her book, How Painting Holds Me to the Earth, how her artistic practice kept her grounded and sane.

An artwork may carry something universal and, in its immediacy and the uniquely personal apprehension experienced as we engage with it, may even keep us in deeper contact with the world around us. Art can prevent us from becoming too self-absorbed because we step into the future as we develop our understanding of it. The German philosopher, Theodor W. Adorno, defined the artwork as that which stands alone, a thing in itself that will brook no other. After my father died, I shared some of my thoughts and feelings about loss with the British poet, Paul Matthews, who told me of his experience after the death of his own father: it was as if he felt naked before God, that he was seen, there was no longer anyone standing between him and that power.

Photograph: © Richard Heys

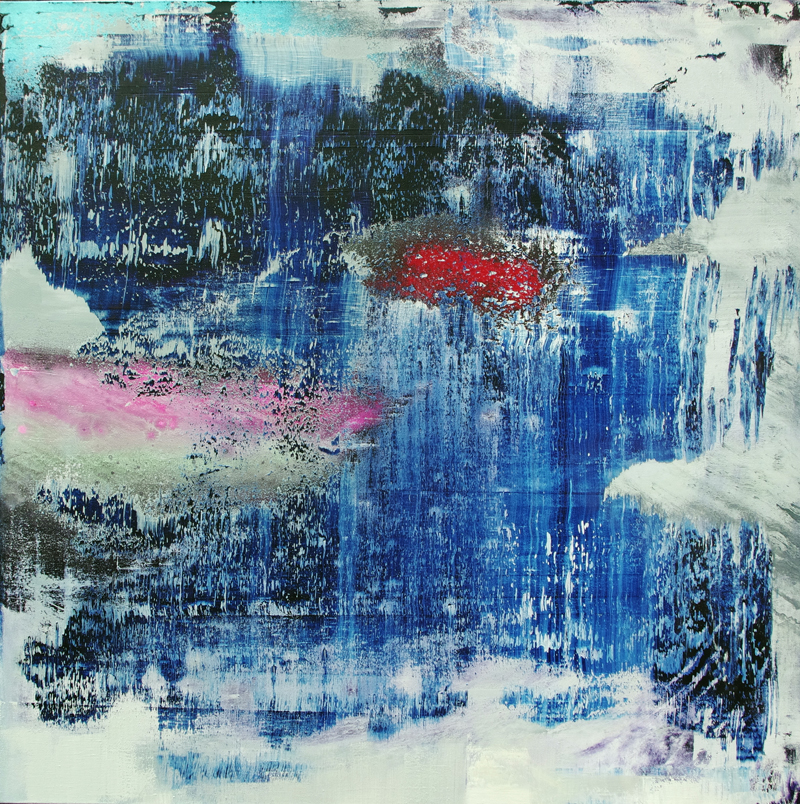

Many of the Holy Mountain paintings include shades of blue. I love how in her A Field Guide to Getting Lost, American writer, Rebecca Solnit, describes her feelings after blue:

For many years, I have been moved by the blue at the far edge of what can be seen, that colour of horizons, of remote mountain ranges, of anything far away. The colour of that distance is the colour of an emotion, the colour of solitude and of desire, the colour of there seen from here, the colour of where you are not. And the colour of where you can never go. For the blue is not in the place those miles away at the horizon but in the atmospheric distance between you and the mountains … ‘Longing’, says the poet, Robert Hass, ‘because desire is full of endless distances.’ Blue is the colour of longing for the distances you never arrive in, for the blue world.

I realized as the veils of indigo and translucent ultramarine blue descended over my canvases that something unknowable had descended between my father and me—I could not follow him to where he had gone but I could sense his presence. In life, some events are truly overwhelming; you cannot know how they will affect you until you are within them. As French writer, Hélène Cixous, writes, “I find my bearings where I become lost …”

Photograph: © Richard Heys

The Holy Mountain series describes a journey, a human journey, the journey to discover oneself as “a little world”. This is a journeying towards wholeness—it may take many years, and how we realize this is unique to each of us. But the arts are surely a key to this development. American writer, Thomas Moore, in his book, Care of the Soul, describes how it is vital to become curators of our own images:

Culturally … we are constantly invited into the depths of ourselves by plays, paintings, sculptures and buildings of past centuries. Art can be a cure for narcissism. The words ‘curator’ and ‘curé’ are essentially the same. By being the curator of our images we care for our souls.

Not that as a painter one has to record these deeply personal imaginations but they may inform and guide us in our maturing in surprising and essential ways.

The immensity of life and the human condition is such that past and future grief may well unravel us at any time. Unless we engage with the arts, unless we can sense ourselves reflected and lose ourselves within music, plays and paintings, we cannot truly imagine a future where we no longer grieve or suffer. All things change and painting can be the finest litmus for this change.

Photograph: © Richard Heys

Post Notes

- Richard Heys’ website

- Richard Heys @ Instagram

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- René Daumal: Mount Analogue

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Josef Pieper: Only the Lover Sings

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Mark Rothko: The Artist’s Reality

- Ditmar Bollaert: Arunachala Pradakshina