Renaissance man

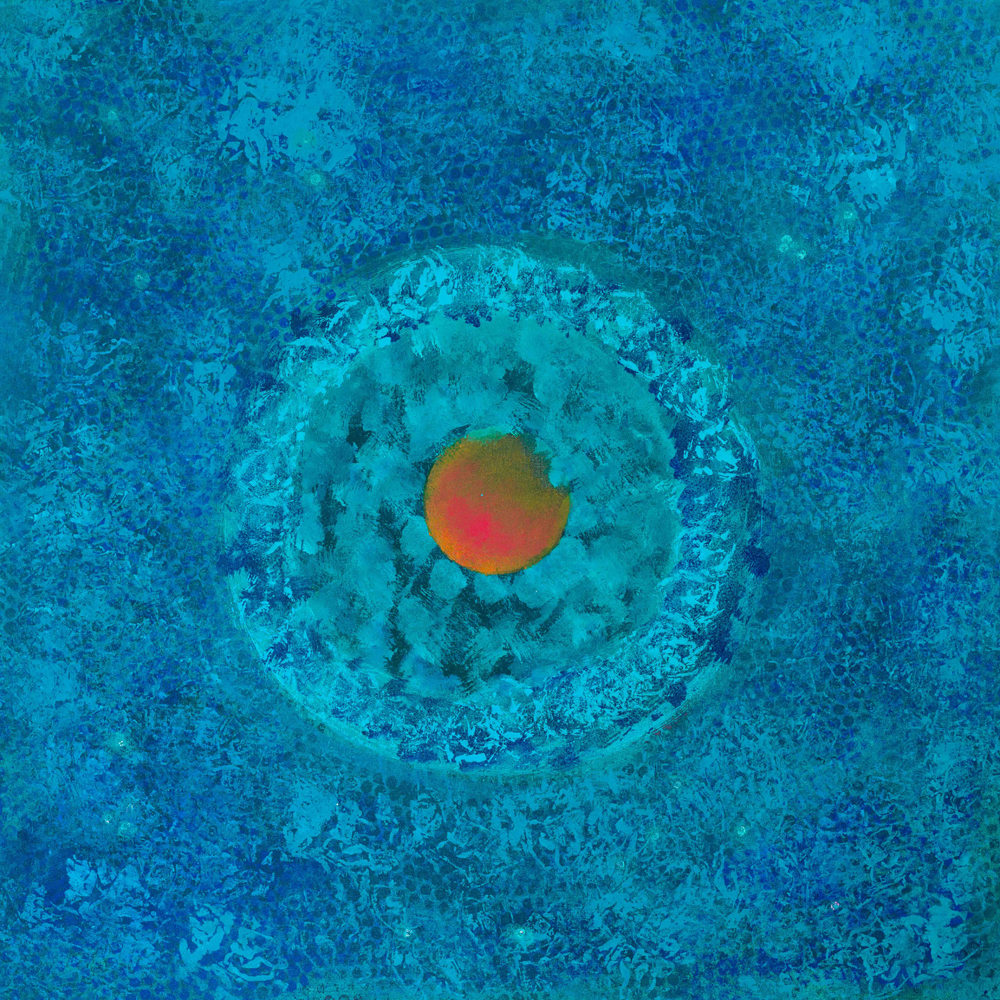

“I attempt to express the inexpressible.

Sometimes it’s a struggle,

sometimes with grace and a silent mind,

the apperception is laid down in one.”

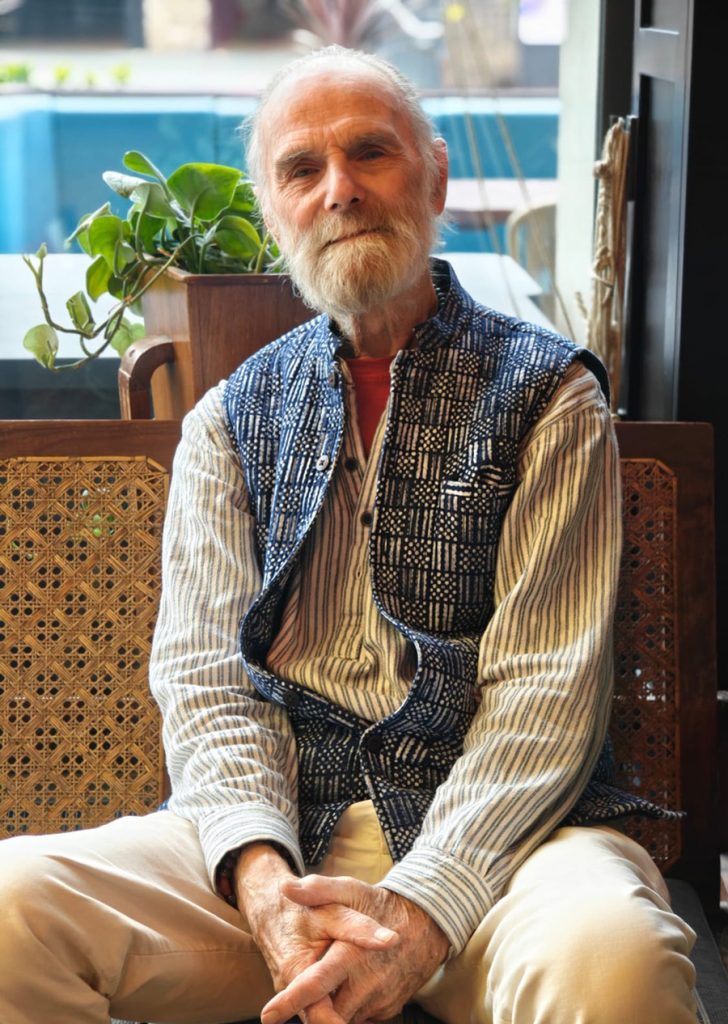

WHEN I WAS researching what to write for Rashid Maxwell‘s eulogy (1937–15th February 2025), I discovered many amazing facts about his extraordinary life that I had not known while he was still with us, not least that British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was his mother’s uncle. But then again, that was Rashid all over—someone who humbly hid his personal attributes under a bushel in search of the higher light.

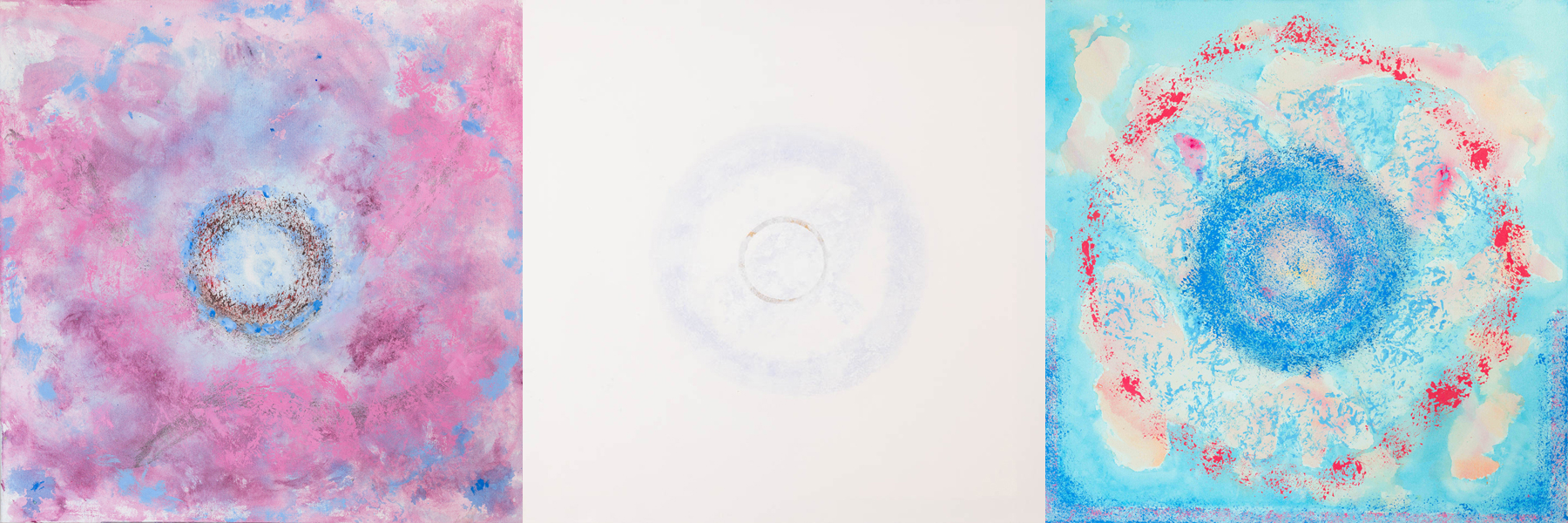

I only met Rashid once, though I was privileged to enjoy a correspondence with him for several years, being a regular contributor to The Culturium. My enduring image of him was at a London art gallery, which was hosting his Drawn In exhibition of his final paintings in the autumn of 2024, as he sat in an elaborate fez hat with a glass of Prosecco, surrounded by his closest family and friends.

Rashid knew at that time he was dying from a rare form of lung cancer, which made the meeting all the more poignant in the knowledge that I would never see him again. Even more notable was how he fully accepted that his mortal form was coming to the end of its natural lifespan and, despite that devastating detail, professed unequivocally that all was well.

“If we don’t give ourselves to something bigger than ourselves,

we waste this life. The arts are signposts to such an end.”

Surviving, as he often said, a restrictive childhood during the Second World War, a tough boarding school education, a stint in the Royal Navy and Oxford University, finally the way of the artist beckoned Rashid to a more meaningful life.

At Chelsea Art College, he met for the first time people who spoke a language he understood; he was taught by, among others, Auerbach, Kossoff and Hoyland. Afterwards, life took him to Malta, East Anglia, then self-sufficiently as an organic farmer in the Welsh Marches and finally, to the ashram of mystical teacher Osho in Poona, India, where he was initiated into sannyas in 1977, being conferred with the name, Swami Deva Rashid (Divine Unerring Quality).

Rashid held various important roles in the Osho commune. At the original Pune ashram, Poona One, he served as Osho’s personal vegetable gardener. In Poona Two, until Osho left his body in 1990, Rashid worked both as a bodyguard and editor.

“Creativity emerges from an empty, silent world

somewhere out of mind.”

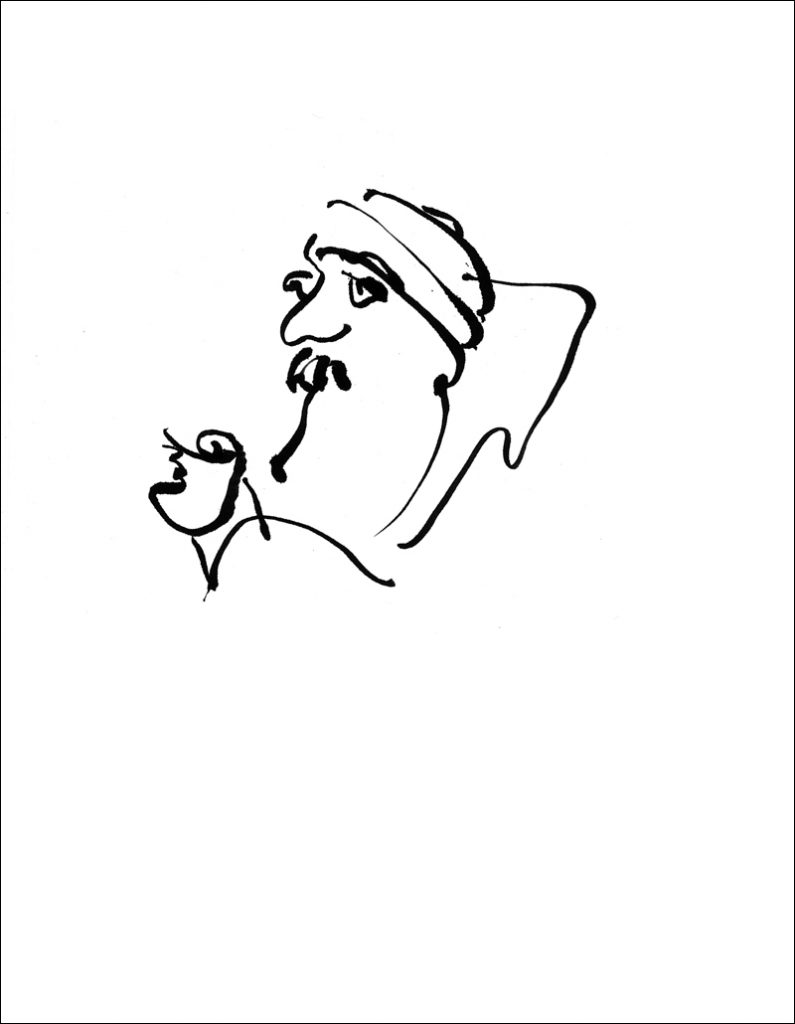

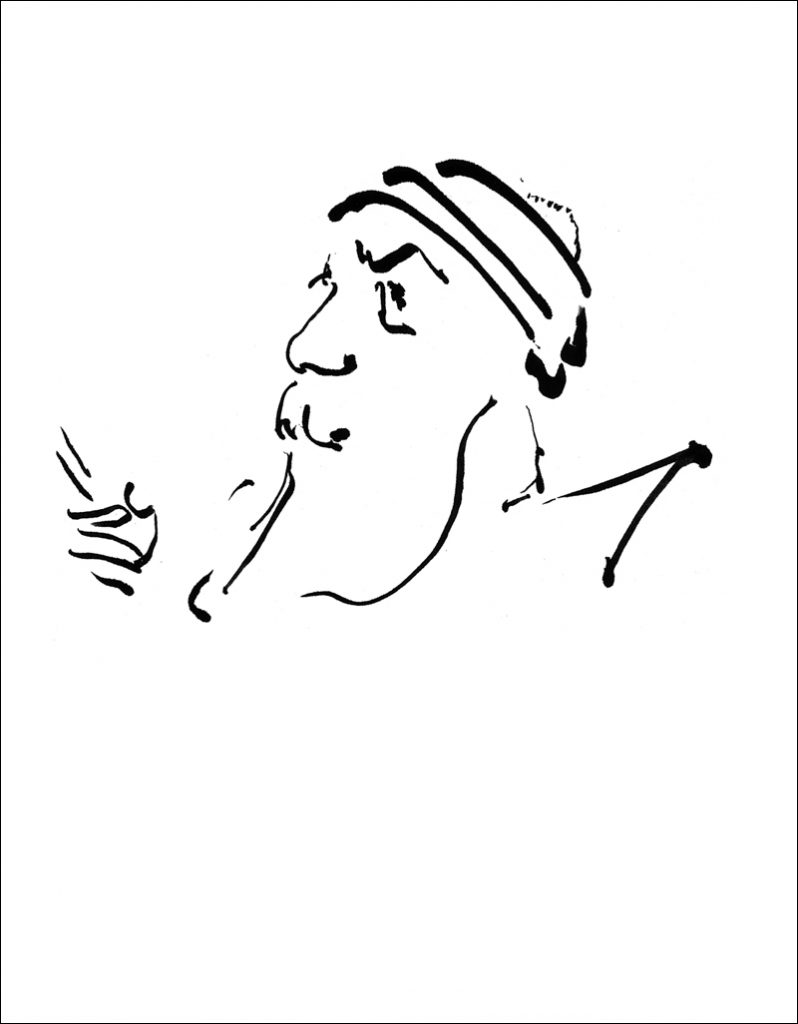

Rashid was an accomplished author and is well known for his memorable and powerful memoir on Osho’s first disciple and secretary, Ma Yoga Laxmi. The Only Life: Osho, Laxmi and a Journey of the Heart, published in 2017, was launched with great fanfare at Oshodham in New Delhi on 11th December 2017, coinciding with what would have been Osho’s 86th birthday. Rashid also authored a novel, The Point of Vanishing, as well as four exquisite volumes of poetry and drawings: Life is One Blessed Thing After Another, Not Knowing Guides Our Feet, Everything is Something Else and A Master for Life.

After Osho’s death in 1990, Rashid worked all over the globe, living in cities, suburbs and even deserts, both in communes and in solitude, earning an income by painting, designing and implementing many eco-environmental projects, including reafforestation, a wetland bird sanctuary and nature reserve, as well as a variety of zendos and meditation halls.

Towards the end of his life, Rashid lived a quiet life with his partner in Devon, often surrounded by his devoted children and numerous grandchildren, where he grew fruit and vegetables, tended to his apiary and watched nature and the birdlife. More remarkably, while silently walking the pathless path, he simultaneously continued to write, draw and paint, now with an unstoppable energy, producing a body of work that was to form the focus of his last exhibition in London. Painting daily, sometimes completing a brand new canvas in a single day, it was as if something had suddenly arisen within him and creatively burst forth, garnering a new lease of life in his final years.

“Subjective art is the art of personal thoughts and emotions.

Objective art is universal; it comes from silence

and is a path to the eternal.

This I understand from Osho.”

In the words of his own family, Rashid was a “vibrant, loving, strong, vulnerable, sensitive, compassionate, wild, non-compromising, energetic, funny, deep, quiet, imaginative, orange and green expression of life”, whose artistic and spiritual legacy will remain forever in the hearts of those who knew him.

A farewell ceremony and celebration will be held on Tuesday, 18th March 2025, between 11.00 a.m. and 2.00 p.m. at Winkleigh Sports Centre, Winkleigh, Devon. Knowing that so many of his beloved family and friends live all over the world, there will be live streaming of the event, with a recording available afterwards. If you feel so inspired, donations in Rashid’s memory may be made to North Devon Hospice, which supported him throughout his final weeks. Full funeral details are outlined on Rashid’s website.

Reflecting personally on Rashid’s passing and outstanding accomplishments, I am reminded how vital it is that we give our brief lives some kind of meaningful purpose, adopt a vision that can guide us to forge an authentic self. I would, therefore, like to offer a closing and utterly compelling extract from an article titled “The Tiger’s Mouth” written by Rashid for Osho News, where he describes his first meeting with his beloved teacher and how Osho became not only his revered master but an enduring example of how to live an enlightened life.

… on December 23, 1977, five of us, including my stepson, were bundling through the Ashram’s Gateless Gate in Pune on our way to meet this man of truth.

That moment of arrival is vivid in my memory. The lightness, the laughter, and the beauty in the faces of the men and women, all dressed in orange robes! It seemed that we were leaving a world of black and white and entering a world of colour. We were quitting winter and entering summer.

Of course, the world is spun from light and dark, from happiness and sadness, from bad as much as good. I came to understand that the ashram was not different from the world; it was in fact a microcosm of it. And more. It was a hotbed, a forcing ground for worldly growth. It was a place to live out all our hopes, desires, and fears. Osho said he was a finger pointing to the moon, the moon that shone in empty space inside each one of us. He spoke with humour and a total lack of dogma. And, each day, we sat in silence, at a distance from our home-spun stories. We sat precariously above the void. Of this golden visit, I recall only the beauty.

On the third day, standing in a long line in the early morning, conspicuous in our blue jeans and our white T-shirts, waiting for the Master’s discourse, watching the soft faces, the little groups of people hugging, the silent inwardness of people, I remember turning to Nicky [Rashid’s wife at the time] and saying, ‘We’re still Christians, aren’t we?’ I don’t know what I meant. I guess I didn’t know my head was in the tiger’s mouth.

Sitting in the back of Buddha Hall behind that silent multitude, Bhagwan appeared to us to be a tiny lighthouse rising from a placid sunrise sea. His voice was softer than the whisper of the wind, and we leaned towards him as plants lean towards the light. He took us on a wondrous journey of the spirit. At the end, he rose and greeted us with folded hands, rotating gradually through all points of the hall. Namaste. He glided to his car and was driven slowly, oh so slowly, round the hall. Those of us at the back and sides swung round to face him.

Bhagwan was seated in his car three meters from me, window down, smiling behind his folded hands. That killed me. The kindness in those eyes, the compassion in the smile, the beauty of those hands—on top of all the wisdom of his words, it was the look of him that killed me. The tiger’s mouth closed. I lay down there and then and cried. I cried a line through every epoch of my life. I cried the tears I’d never cried through childhood, adolescence, and my early manhood. I cried for love, I cried for hate, I cried for loss, I cried for gain, I cried for everything created, and for everything destroyed. I cried beyond all possibility of words …

[Extract taken from “The Tiger’s Mouth” by Rashid Maxwell, Osho News]

Post Notes

- Feature image: © Rashid Maxwell, Drawn In, And it’s a Mirror, Nothing From Nothing 07,

Acrylic on canvas 75cm x 75cm. - Rashid Maxwell’s website

- North Devon Hospice

- Osho News

- Rashid Maxwell: Drawn In

- Rashid Maxwell: A Master for Life

- Rashid Maxwell: To Save the Planet With a Paintbrush

- Rashid Maxwell: Contagion of Silence

- Eulogy for Alan Jacobs

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme