Image: Public Domain

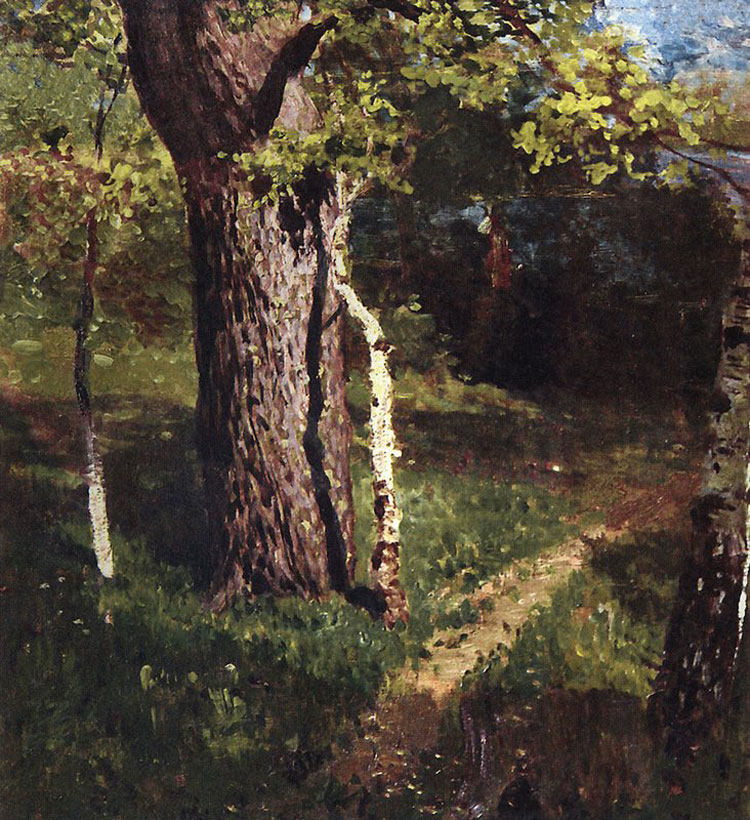

The plantation of God

In the woods […] a man casts off his years, as the snake his slough, and at what period soever of life, is always a child. In the woods, is perpetual youth. Within these plantations of God, a decorum and sanctity reign, a perennial festival is dressed and the guest sees not how he should tire of them in a thousand years. In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life,—no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes), which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God. The name of the nearest friend sounds then foreign and accidental: to be brothers, to be acquaintances,—master or servant, is then a trifle and a disturbance. I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty. In the wilderness, I find something more dear and connate than in streets or villages. In the tranquil landscape, and especially in the distant line of the horizon, man beholds somewhat as beautiful as his own nature.

T. S. ELIOT famously said in The Waste Land that April is the cruellest month. For a long time, I never really understood what he was talking about until I myself grew deeply weary of life and discovered how the rejuvenating power of nature brought about my own depressive feelings regarding the fragility of existence into stark relief.

And yet, as I have graciously come to accept the state of my own mortality, I find I only happen upon joy and solace during the spring and summer months. Somehow, the peace, beauty and stillness of the great outdoors obliterates all traces of my bewildered self and my soul is bathed in redemptive light.

Image: Public Domain

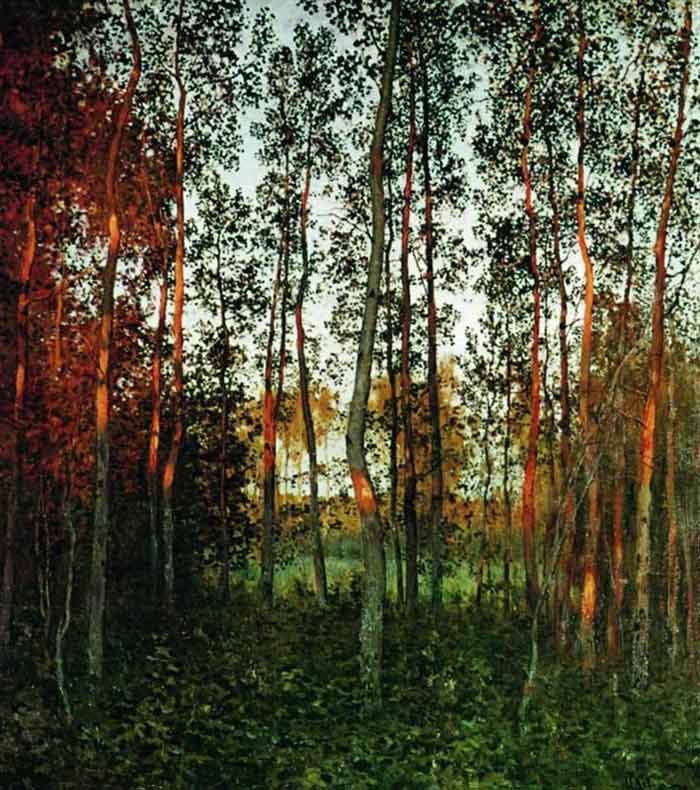

A nobler want of man is served by nature, namely, the love of Beauty […] Such is the constitution of all things, or such the plastic power of the human eye, that the primary forms, as the sky, the mountain, the tree, the animal, give us a delight in and for themselves; a pleasure arising from outline, colour, motion and grouping. This seems partly owing to the eye itself. The eye is the best of artists. By the mutual action of its structure and of the laws of light, perspective is produced, which integrates every mass of objects, of what character soever, into a well coloured and shaded globe, so that where the particular objects are mean and unaffecting, the landscape which they compose is round and symmetrical. And as the eye is the best composer, so light is the first of painters. There is no object so foul that intense light will not make beautiful. And the stimulus it affords to the sense, and a sort of infinitude which it hath, like space and time, make all matter gay. Even the corpse has its own beauty. But besides this general grace diffused over nature, almost all the individual forms are agreeable to the eye, as is proved by our endless imitations of some of them, as the acorn, the grape, the pine-cone, the wheat-ear, the egg, the wings and forms of most birds, the lion’s claw, the serpent, the butterfly, sea-shells, flames, clouds, buds, leaves and the forms of many trees, as the palm.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (25th May 1803–27th April 1882) was acutely aware of the healing properties of nature, composing some of the most exquisite prose in the English language on the restorative power of sylvan landscapes and the beauty of Mother Earth.

Over the course of his career, Emerson gave hundreds of public lectures, which were later reproduced in various collections of essays. “Nature”, first delivered in Boston and later published in 1836, has become a seminal text not only for outlining his views on Transcendentalism—an Idealist philosophy purporting that divinity suffuses all creation—but also how in particular the natural world offers an immediate conduit to God.

Image: Public Domain

[The] simple perception of natural forms is a delight. The influence of the forms and actions in nature is so needful to man, that, in its lowest functions, it seems to lie on the confines of commodity and beauty. To the body and mind which have been cramped by noxious work or company, nature is medicinal and restores their tone. The tradesman, the attorney comes out of the din and craft of the street, and sees the sky and the woods, and is a man again. In their eternal calm, he finds himself. The health of the eye seems to demand a horizon. We are never tired, so long as we can see far enough.

But in other hours, Nature satisfies by its loveliness, and without any mixture of corporeal benefit. I see the spectacle of morning from the hill-top over against my house, from day-break to sun-rise, with emotions which an angel might share. The long slender bars of cloud float like fishes in the sea of crimson light. From the earth, as a shore, I look out into that silent sea. I seem to partake its rapid transformations: the active enchantment reaches my dust and I dilate and conspire with the morning wind. How does Nature deify us with a few and cheap elements! Give me health and a day, and I will make the pomp of emperors ridiculous. The dawn is my Assyria; the sun-set and moon-rise my Paphos, and unimaginable realms of faerie; broad noon shall be my England of the senses and the understanding; the night shall be my Germany of mystic philosophy and dreams.

Composed of an introduction and eight short chapters—Nature, Commodity, Beauty, Language, Discipline, Idealism, Spirit and Prospects—Emerson’s beautifully written thesis expounds the relationship between nature and man. For the American essayist, community populated with people represents ugliness, immorality, suffering; nature, by contrast, embodies beauty, benevolence, peace.

Moreover, in order for there to be any meaning to our existence, we must disengage ourselves from the machinations of society and wholeheartedly embrace the solitary life, through which we may imbibe most fully the “wholeness” of the natural world, purging ourselves of all our daily cares and finding mystical union with the universe.

Image: Public Domain

To go into solitude, a man needs to retire as much from his chamber as from society. I am not solitary whilst I read and write, though nobody is with me. But if a man would be alone, let him look at the stars. The rays that come from those heavenly worlds, will separate between him and what he touches. One might think the atmosphere was made transparent with this design, to give man, in the heavenly bodies, the perpetual presence of the sublime. Seen in the streets of cities, how great they are! If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore; and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God which had been shown! But every night come out these envoys of beauty and light the universe with their admonishing smile.

Emerson was by no means the first writer to espouse a retreat from the active life; from time immemorial, philosophers, sages and poets have championed the reclusive existence as the only means to acquiring well-being, equilibrium and inner calm, none so eloquently fashioned in prose such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Meditations of a Solitary Walker, Michel de Montaigne’s On Solitude and fellow Transcendentalist, Henry David Thoreau’s Walden; or, Life in the Woods.

And in poetry, the cool wit of the Metaphysical poets, such as Andrew Marvell, and later, in the emotional lyricism of the Romantic poets, such as Percy Bysshe Shelley, a pilgrimage to the Arcadian ideal was similarly extolled. Indeed, Emerson’s unified, nondualistic interpretation of the world inaugurated him into an enduring heritage of mystical thinkers, irrevocably linking him to a literary expressionism of the divine.

Image: Public Domain

All men are in some degree impressed by the face of the world; some men even to delight. This love of beauty is Taste. Others have the same love in such excess, that, not content with admiring, they seek to embody it in new forms. The creation of beauty is Art […] The production of a work of art throws a light upon the mystery of humanity. A work of art is an abstract or epitome of the world. It is the result or expression of nature, in miniature. For, although the works of nature are innumerable and all different, the result or the expression of them all is similar and single. Nature is a sea of forms radically alike and even unique. A leaf, a sun-beam, a landscape, the ocean, make an analogous impression on the mind. What is common to them all,—that perfectness and harmony, is beauty. The standard of beauty is the entire circuit of natural forms,—the totality of nature; which the Italians expressed by defining beauty ‘il piu nell’ uno’. Nothing is quite beautiful alone: nothing but is beautiful in the whole. A single object is only so far beautiful as it suggests this universal grace. The poet, the painter, the sculptor, the musician, the architect, seek each to concentrate this radiance of the world on one point, and each in his several works to satisfy the love of beauty which stimulates him to produce. Thus is Art, a nature passed through the alembic of man. Thus in Art, does nature work through the will of a man filled with the beauty of her first works.

Akin to Socrates’ address in Plato’s Symposium, in which he expounds how love for “beautiful bodies” can lead to worship of the godhead, Emerson advances his own theory of aesthetics and the notion that the beauty of nature inspires adoration and devotion, and in turn, inspires man to capture its essence in creative form.

Thus, beauty’s baptismal grace arouses the imaginative impulse to produce sacred works of art—be it poetry, painting or music—whereby the macroscopic Universal Being is distilled in miniature within a microscopic point.

Image: Public Domain

There is still another aspect under which the beauty of the world may be viewed, namely, as it becomes an object of the intellect. Beside the relation of things to virtue, they have a relation to thought. The intellect searches out the absolute order of things as they stand in the mind of God, and without the colours of affection. The intellectual and the active powers seem to succeed each other and the exclusive activity of the one, generates the exclusive activity of the other. There is something unfriendly in each to the other, but they are like the alternate periods of feeding and working in animals; each prepares and will be followed by the other. Therefore does beauty, which, in relation to actions, as we have seen, comes unsought, and comes because it is unsought, remain for the apprehension and pursuit of the intellect; and then again, in its turn, of the active power. Nothing divine dies. All good is eternally reproductive. The beauty of nature reforms itself in the mind, and not for barren contemplation, but for new creation.

As well as fulfilling an artistic sensibility reflected in the eyeball, nature similarly serves as a vehicle of thought and discipline for the mind, characterized by a search for the absolute order of things.

Through use of the cognitive faculties of reason and understanding, the ultimate message that we receive from nature, Emerson believes, is the recognition and acceptance of a noumenal essence pervading both the universe and the individualized self.

Image: Public Domain

The world thus exists to the soul to satisfy the desire of beauty. This element I call an ultimate end. No reason can be asked or given why the soul seeks beauty. Beauty, in its largest and profoundest sense, is one expression for the universe. God is the all-fair. Truth, and goodness, and beauty, are but different faces of the same All. But beauty in nature is not ultimate. It is the herald of inward and eternal beauty, and is not alone a solid and satisfactory good. It must stand as a part, and not as yet the last or highest expression of the final cause of Nature.

And thus, Emerson concludes, God created the world for the emancipation of man through the beauty of nature, leading us back to the transcendental soul.

Indeed, for most of us on a spiritual journey, being a “part or particle of God” only arrives when we cast off the vestiges of mammon and all our worldly ambitions and assimilate the beauteousness of the natural world. As Emerson so reverently reminds us: “The aspect of nature is devout. Like the figure of Jesus, she stands with bended head and hands folded upon the breast. The happiest man is he who learns from nature the lesson of worship.”

Post Notes

- The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Waldeinsamkeit

- Henry David Thoreau: Walking

- Robert Louis Stevenson: An Apology for Idlers

- John Ruskin: On Art and Life

- Michel de Montaigne: On Solitude

- Rousseau: Meditations of a Solitary Walker

- Andrew Marvell: On a Drop of Dew

- Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Cloud

- Leo Tolstoy: A Confession