How the ancients’ love of chariot racing became a metaphor for the human condition

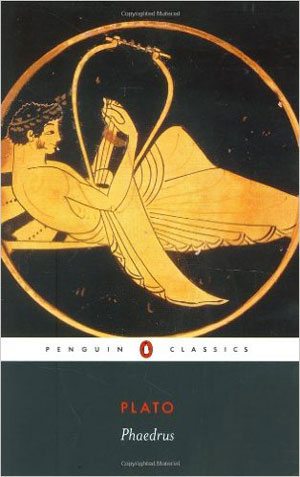

Let us adopt this method and compare the soul to a winged charioteer and his team acting together. Now all the horses and charioteers of the gods are good and come of good stock, but in other beings there is a mixture of good and bad.

First of all we must make it plain that the ruling power in us men drives a pair of horses, and next that one of these horses is fine and good and of noble stock, and the other opposite in every way. So in our case, the task of the charioteer is necessarily a difficult and unpleasant business.

—Plato, Phaedrus

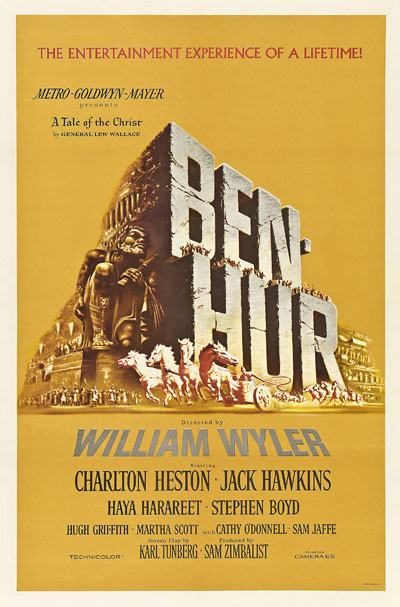

THE ALLEGORY OF the charioteer is one we see oft repeated throughout material that is didactic in nature, both in literature and in film. In the epic Hollywood historical drama, Ben-Hur (1959) directed by William Wyler, Judah Ben-Hur (Palestinian Jewish “goodie” played by Charlton Heston) and Messala (Roman “baddie” played by Stephen Boyd) pitch their equestrian skills against each other during one of cinema’s most notorious and iconic scenes—a chariot race lasting to the very death.

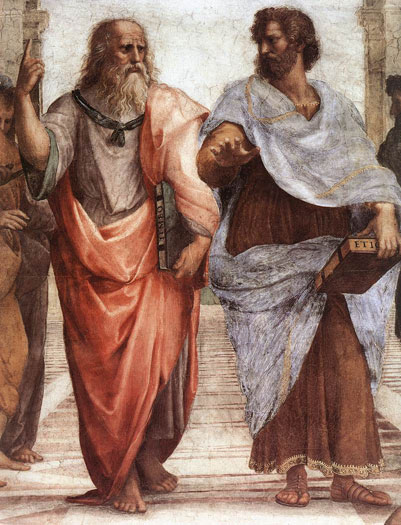

Phaedrus, written by Plato (428/7 BC–348/7 BCE) sometime around 370 BCE, similarly uses the charioteer allegory, albeit with more palatable effect. Phaedrus, an Athenian aristocrat, and Socrates (470/69–399 BCE) sit outside the city walls, close to a stream, in the shade of a plane tree away from the heat of the midday sun. As the cicadas pulse in the grass, they discuss the art of rhetoric, metempsychosis (the Greek tradition of reincarnation) and the nature of erotic love, a state akin to “divine madness” and inspired by the gods.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Eternal life

The centrepiece of the text, however, is an account on the immortality of the soul. According to Socrates, the charioteer represents the intellect, one horse represents rational or moral impulse while the other horse represents irrational passion.

The role of the charioteer, who is endowed with a fine set of feathery wings, is to drive his horses onward and upward, keeping his team working together in harmony towards the realm of the gods, a place of illumination, reality and truth.

Plato then describes how the soul goes on a great circuit to discover “enlightenment”, the wings’ function enabling flight ever higher, wherein it is nourished by the presence of wisdom, goodness and the Divine.

Evil and ignorance in the soul, however, make the wings wither and disappear:

When it is perfect and winged it moves on high and governs all creation, but the soul that has shed its wings falls until it encounters solid matter. There is settles and puts on an earthly body, which appears to be self-moving because of the power of soul that is in it, and this combination of soul and body is given the name of a living being and is termed mortal.

—Plato, Phaedrus

And thus, the soul is incarnated into one of nine persons, according to how much truth was beheld before it fell, Icarus-like, to the earth: philosopher; king/civic leader; politician/businessman; physician; prophet; poet/artist; craftsman/farmer; sophist; or tyrant.

The divine madness of erotic love

In a further dialogue about the awakening of love in the lover for the beloved, Socrates recounts how the horses react when the soul encounters the sight of a beautiful boy and the passion it bestirs:

So they draw near, and the vision of the beloved dazzles their eyes. When the driver beholds it the sight awakens in him the memory of absolute beauty; he sees her again enthroned in her holy place attended by chastity.

At the thought he falls upon his back in fear and awe, and in so doing inevitably tugs the reins so violently that he brings both horses down upon their haunches; the good horse gives way willingly and does not struggle, but the lustful horse resists with all its strength.

Finally, after several repetitions of this treatment, the wicked horse abandons his lustful ways; meekly now he executes the wishes of his driver, and when he catches sight of the loved one is ready to die of fear. So at last it comes about that the soul of the lover waits upon his beloved in reverence and awe.

—Plato, Phaedrus

Rather than dismiss the love inspired in the lover as mere romantic foolery, Socrates declares that a lover’s friendship is noble and blessed by the very gods themselves.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Allegory of the charioteer in Eastern literature

Plato was not the only philosopher to use the metaphor of the chariot. The Katha Upanishad tells the tale of Nachiketa, son of sage Vajasravasa, and his encounter with Yama, the God of Death. During Yama’s discourse on the teachings, he recalls the parable of the chariot:

Know the Self as Lord of the chariot, the body as the chariot itself, the discriminating intellect as the charioteer, and the mind as the reins. The senses, say the wise, are the horses; selfish desires are the roads they travel.

—Katha Upanishad, 1.3.3-4

And of course, the greatest epic of all is the Bhagavad Gita, a dialogue between the Lord Sri Krishna and the Pandava Prince Arjuna on the battlefield just before the start of the Kurukshetra War.

Arjuna is despondent and confused about the impending bloodshed between the Pandavas and the Kauravas, both royal families to whom he is related. He therefore turns to his charioteer, Sri Krishna, to ask for his advice and the text of the Gita is his response.

When truth is revealed

As with all allegories and metaphors, their purpose is to point to something higher and more noble, which once understood may be unbridled and put to bed:

Nevertheless, the fact is this; for we must have the courage to speak the truth, especially when truth itself is our theme. The region of which I speak is the abode of the reality without colour or shape, intangible but utterly real, apprehensible only by intellect which is the pilot of the soul.

So the mind of a god, sustained as it is by pure intelligence and knowledge, like that of every soul, which is destined to assimilate its proper food, is satisfied at last with the vision of reality, and nourished and made happy by the contemplation of truth, until the circular revolution brings it back to its starting point.

And in the course of its journey it beholds absolute justice and discipline and knowledge, not the knowledge which is attached to things which come into being, not the knowledge which varies with the objects which we now call real, but the absolute knowledge which corresponds to what is absolutely real in the fullest sense.

And when in like manner it has beheld and taken its fill of the other objects which constitute absolute reality, it withdraws again within the vault of heaven and goes home. And when it comes home the charioteer sets his horses at their manger and puts ambrosia before them and with it a draught of nectar to drink.

—Plato, Phaedrus

Post Notes

- Ben-Hur on Filmsite.org

- Plato on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Socrates on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Marcus Aurelius: Meditations

- Sappho: The Tenth Muse

- Seneca: On Tranquillity of Mind

- Josef Pieper: Only the Lover Sings

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth

- Kathleen Raine: The Land Unknown

- Plotinus: Enneads