Photograph: Public Domain

Sensing and knowing the ineffable nature of Divinity through contemplative art

“Contemplative art has the potential to bring the reader home

to their Divine Self, their Real Self, their Real Nature.”

Philip Brown is an independent researcher in the field of Contemplative Studies. He spent his working life teaching children with severe and multiple disabilities and developing training programmes to prevent the physical and sexual abuse of people with disabilities. Baptized and confirmed in The Church of England, he has practised meditation for 40 years and over the past two decades has studied and practised the Dzogchen Teachings of Tibetan Buddhism. Prior to that, he practised Transcendental Meditation and Vipassana (Insight) Meditation. Since the age of 14, when he first read Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy, he has had an abiding interest in this philosophy and the field of comparative religion.

A regular contributor to The Culturium, in this month’s feature, Philip explores the way in which the practice and contemplation of art, whatever its genre or discipline, may lead to a taste of the divine.

o0o

IN THIS CENTURY, as much if not more than in any other, humanity needs the wisdom and compassion afforded by mystical/contemplative knowledge and experience of the true nature of Divinity. Despite its ineffability, but consistent with the writings of mystics, Divinity may be provisionally defined as:

The Absolute Undifferentiated Unity of Being which, as the Ground of Being, is both the inherent Primordial Nature of, and origin of, all manifest forms, human or otherwise.

Being ineffable, Divinity’s true nature is difficult to express and experience of it difficult to foster. It may, however, be known and experienced through the diligent and sustained application of the religious and spiritual practices of contemplative prayer, meditation and nondual contemplation, as well as through some of the art practice referred to as religious, spiritual or sacred. In this blog, the case will be made for describing art that fosters this knowledge and experience as contemplative art.

The relationship between contemplative art and nondual contemplation

Dualistic thinking is the ego’s preferred way of seeing reality. It is essentially binary, either/or thinking in which one knows by comparison, opposition and differentiation. It divides one’s field of awareness into subject and object and through it, the world is perceived as polarities such as good/evil, pretty/ugly, smart/stupid. Dualistic thinking is conceptual by nature whereas nondual contemplation is beyond, and hence not limited to, conceptual thinking. When one is in the state of nondual contemplation, one abides in an ever-present awareness, which not only subsumes one’s ego, thoughts, emotions and sensory experiences but extends beyond exclusive identification with these things.

As Divinity is directly apprehended through nondual contemplation, rather than comprehended through dualistic thinking processes, then religious, spiritual, sacred or other art is unlikely to be contemplative art if it does not arise from, or is not referenced to, or perceived/experienced from the state of nondual contemplation in some way, or arise from the states of consciousness that are the outcomes of the practices of meditation and contemplative prayer, which are known to be facilitative of nondual contemplation. That is, non-contemplative art, be it religious, spiritual, sacred or profane, relates to dualistic thinking, whereas contemplative art has at least some connection with nondual contemplation.

Examples of the relationship between contemplative art and nondual contemplation

Nondual contemplation has a number of potential roles to play in the creation and/or appreciation of contemplative art. These roles will be explained using five examples related to such art. For the sake of brevity and readability, “Nondual contemplation and the states of consciousness that are the outcomes of the practices of meditation and contemplative prayer known to be facilitative of nondual contemplation”, will henceforth be referred to collectively as “transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness”.

Photograph: Public Domain

(1.) The artwork and/or biographies of William Blake, William Wordsworth, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Honoré de Balzac, Henry Thoreau, Alfred Lord Tennyson and Jack Kerouac indicate that their artwork was profoundly influenced by life-changing experiences of transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness. It is therefore likely that some, if not most of their artwork, is contemplative art given these states of consciousness experienced by the artist prior to or during the creation of the artwork. Consider for example the writing of Ralph Waldo Emerson. In his work, Nature, he says:

In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life,—no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

This is also exemplified by the following quote from Jack Kerouac’s “sutra”, titled The Scripture of the Golden Eternity:

I was smelling flowers in the yard, and when I stood up I took a deep breath and the blood all rushed to my brain and I woke up dead on my back in the grass. I had apparently fainted, or died, for about sixty seconds. My neighbor saw me but he thought I had just suddenly thrown myself on the grass to enjoy the sun. During that timeless moment of unconsciousness I saw the golden eternity. I saw heaven. In it nothing had ever happened, the events of a million years ago were just as phantom and ungraspable as the events of now, or the events of the next ten minutes. It was perfect, the golden solitude, the golden emptiness, Something-Or-Other, something surely humble. There was a rapturous ring of silence abiding perfectly. There was no question of being alive or not being alive, of likes and dislikes, of near or far, no question of giving or gratitude, no question of mercy or judgment, or of suffering or its opposite or anything. It was the womb itself, aloneness, alaya vijnana the universal store, the Great Free Treasure, the Great Victory, infinite completion, the joyful mysterious essence of Arrangement. It seemed like one smiling smile, one adorable adoration, one gracious and adorable charity, everlasting safety, refreshing afternoon, roses, infinite brilliant immaterial gold ash, the Golden Age. The ‘golden’ came from the sun in my eyelids, and the ‘eternity’ from my sudden instant realization as I woke up that I had just been where it all came from and where it was all returning, the everlasting So, and so never coming or going; therefore I call it the golden eternity but you can call it anything you want.

o0o

(2.) Even if an artwork does not directly evoke the experience of transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness, its description of these states and/or the contemplative practices that foster them may, nonetheless, be a stimulus for the observer to commence or continue one or more of these practices.

With regard to the following literature, this was certainly the case for the author of this blog: Tsultrim Allione’s biographical work, Women of Wisdom; Fakhruddin ‘Iraqi’s poetic work, Divine Flashes; Hanshan’s Cold Mountain poems; the anonymous Russian autobiographical novel, The Way of a Pilgrim; Jack Kerouac’s work, The Scripture of the Golden Eternity and his autobiographical novels The Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels; Aldous Huxley’s utopian novel, Island; Herman Hesse’s novels Siddhartha and Journey to the East; W. Somerset Maugham’s novel, The Razor’s Edge; Thomas Merton’s autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain; and some poems by Anne Waldman.

The author considers these to be works of contemplative art because of the way in which they fostered and nurtured his contemplative practice. For example, the following is a composite of excerpts from Kerouac’s The Scripture of the Golden Eternity. As previously described, the “Golden Eternity” refers to Divinity:

Did I create that sky? Yes, for, if it was anything other than a conception in my mind I wouldn’t have said Sky’—That is why I am the golden eternity. There are not two of us here, reader and writer, but one, one golden eternity, One-Which-It-Is, That-Which-Everything-Is.

***

Strictly speaking, there is no me, because all is emptiness. I am empty, I am non-existent. All is Bliss.

This truth law has no more reality than the world. You are the golden eternity because there is no me and no you, only one golden eternity.

***

God is not outside us but just us, the living and the dead, the never-lived and the never-died. That we should learn it only now, is supreme reality, it was written a long time ago in the archives of universal mind, it is already done, there’s no more to do.

This is the knowledge that sees the golden eternity in all things, which is us, you, me, and which is no longer us, you, me.

This work by Kerouac was a catalyst for the author of this blog to further his contemplative practice with particular reference to Buddhist epistemology.

Guggenheim Museum, Introduction to James Turrell

(3.) The observer’s experience of transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness can influence their designation of an artwork as “contemplative”. For example, this applies in relation to the author’s contemplative experience of the artworks of James Turrell. Turrell is a Quaker whose works are clearly contemplative even though they are not explicitly so in terms of typical religious or spiritual motifs. In his own words:

My work is about space and the light that inhabits it. It is about how you confront that space and plumb it with vision. It is about your seeing, like the wordless thought that comes from looking into fire.

Commentary on the Art21 website [a nonprofit organization dedicated to inspiring a more creative world through the works and words of contemporary artists] says:

Turrell’s art places viewers in a realm of pure experience … His fascination with the phenomena of light is ultimately connected to a very personal, inward search for mankind’s place in the universe. Influenced by his Quaker faith, which he characterizes as having a ‘straightforward, strict presentation of the sublime’, Turrell’s art prompts greater self-awareness through a similar discipline of silent contemplation, patience and meditation. His ethereal installations enlist the common properties of light to communicate feelings of transcendence and the divine.

Turrell’s artwork has been exhibited in Canberra, the home city of the author. In 2010, he created an extraordinary “SkySpace” installation called Within without in the grounds of the National Gallery of Australia. Four years later, a major retrospective of his work was exhibited at that gallery. Based on the author’s experience of transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness, his own contemplative experience of these artworks and the experience of them by other contemplative practitioners known to him, it is clear that these works are contemplative art. Readers are encouraged to explore Turrell’s artwork via his website. The YouTube video above provides an informative interview with him.

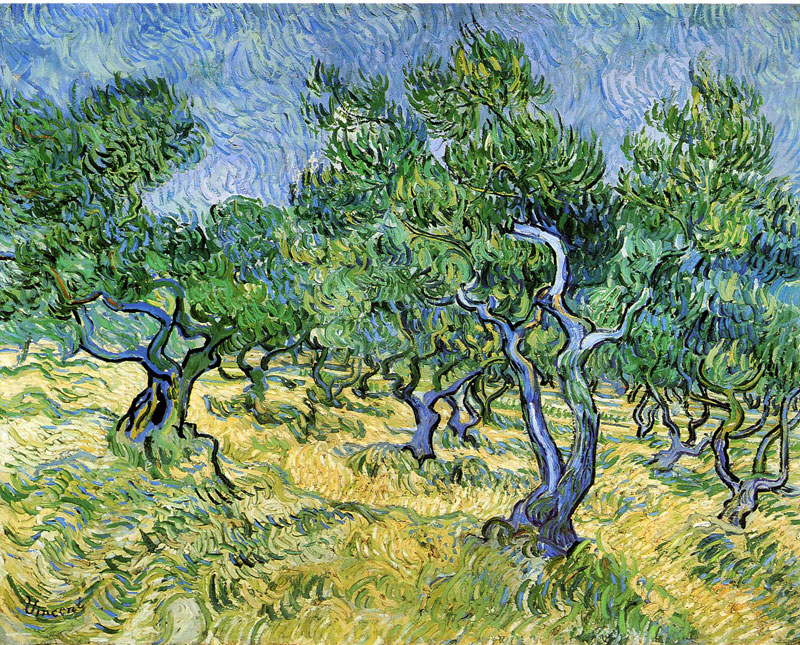

Photograph: Public Domain

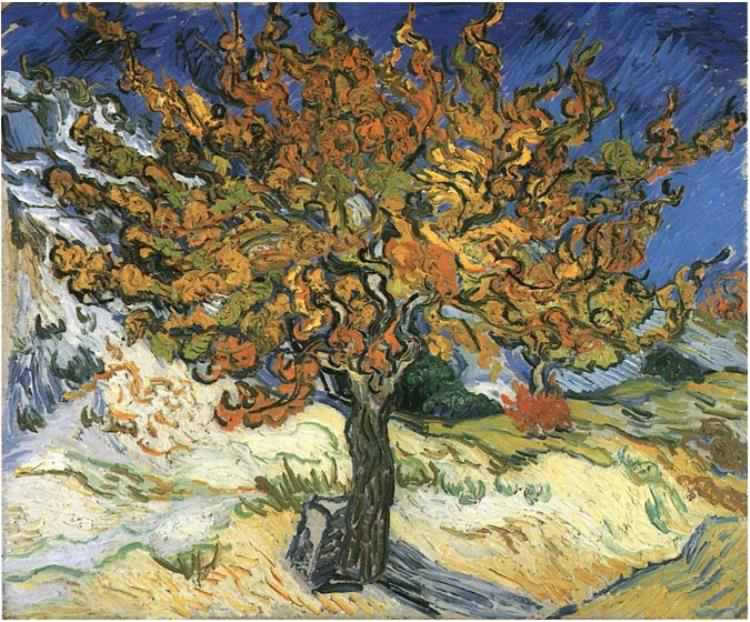

(4.) An artwork, whether it was intended to be contemplative or not, may be considered contemplative art when it fosters transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness in the observer. For example, in his book, The Eye of the Spirit, Ken Wilber draws our attention to the transformative potential of art, irrespective of its content, to facilitate the transcendence of the observer’s ego. Although referring to visual art, his observations are equally applicable to other art forms:

When I directly view, say, a great van Gogh, I am reminded of what all superior art has in common: the capacity to take your breath away … When we look at any beautiful object (natural or artistic), we suspend all other activity, we are simply aware … In that contemplative awareness, our own egoic grasping in time comes momentarily to rest. We relax into our basic awareness. We rest with the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. We are face to face with the calm, the eye in the center of the storm. We are not agitating to change things: we contemplate the object as it is. Great art has this power, this power to grab your attention and suspend it: we stare, sometimes awestruck, sometimes silent, but we cease the restless movement that otherwise characterizes our every waking moment.

o0o

(5.) Some religious traditions have artistic activities that are themselves contemplative practices. These include but are not limited to: icon painting and meditation focused on icon images from the Eastern Orthodox Church; Gregorian chant from Western Catholic Christianity; Sufi/Dervish dancing; Zen Buddhist art practices; and from Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, Vajra dance based on the teachings of Dzogchen Master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu. Also, Thangka painting and the creation of sacred sand mandalas and Dharma art based on the teachings of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

Furthermore, the “performance” of religious rites in general can under certain conditions constitute contemplative art. These rites may include ritual singing or chanting, the wearing of ritual clothing and jewellery, and the performance of ritual actions related to body posture, hand gesture and the use of ritual objects. The performance of a religious rite is a form of religious, sacred or spiritual art when undertaken using dualistic thinking processes. It is, however, contemplative art when undertaken while in a transpersonal/contemplative state of consciousness or with the intention to foster or enter into a transpersonal/contemplative state of consciousness.

Examples of artistic activities whose principal function is contemplative practice

Gregorian Chant

As explained by Marius Schneider in his paper, On Gregorian Chant and the Human Voice:

Gregorian chant is a form of prayer. It cannot be understood merely through its music but must be approached through the experience of prayer. It stands midway between the spoken word of prayer and pure mystical contemplation because it is based on concrete words whose logical meaning is sometimes restricted and at other times extended to the very limits of hyperlogical thought.

The reader may explore this form of chant through the following YouTube videos. One is of the monks of the Abbey of St Ottilien, Germany.

Os Melhores Louvores e Adoração, Gregorian Chants in Latin Sung by Monks of the Abbey of St Ottilien

While the other shows the choir of Claire College, Cambridge, singing Gregorio Allegri’s ethereal Miserere.

Gregorio Allegri, Miserere

Vajra dance based on the teachings of the Dzogchen Master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu

According to an official website for this practice:

The dance of the Vajra is a method of movement in contemplation … Through dancing … specific energy points in our body [are activated and coordinated] according to an ancient knowledge of channels and chakras. In this way the Vajra dance dissolves energy blocks, harmonizes the three main aspects of our being—body, energy and mind—and develops presence and awareness …

As a practitioner of Vajra dance, the author confirms these statements on the basis of personal experience. The following YouTube video reveals the gentle, flowing, meditative and contemplative nature of this dance.

DzogchenTV, The Vajra Dance That Benefits Beings

The practice of Dharma art as conceived by the artist and meditation Master, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

As stated in the publisher’s notes of Trungpa Rinpoche’s book, True Perception:

Genuine art has the power to awaken and liberate … Dharma art [is] any creative work that springs from an awakened state of mind, characterized by directness, unselfconsciousness and nonaggression.

Elsewhere in this book, Trungpa explains:

As far as Dharma art or absolute experience is concerned, along with our experience, we begin to see things as they are, touch on things as they are. Then we begin to be with object perceptions, without accepting or rejecting. We simply try to be that way. There is a kind of standing-still quality, or stalemate, in which comments and remarks become unimportant, and seeing things as they are becomes the real thing.

One form of this Dharma art is calligraphy. The following YouTube video shows Tibetan Buddhist calligraphy masters demonstrating this art form.

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, Buddhist Calligraphy Masters Part 1 – Shambhala

The resultant artwork from the three artistic activities just described is clearly contemplative art because each is a contemplative practice in its own right. Furthermore, if transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness occur in the artist solely or in part through the act of creating the artwork, then the resultant artwork can also be designated contemplative art on that basis.

o0o

Summary: nondual contemplation and contemplative art

Collectively, the above examples show how the artworks and art practices described have one or more connections with nondual contemplation and on that basis can be designated contemplative art. As we have seen, these connections include:

- the transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness experienced by the artist prior to or during the creation of the artwork;

- the artwork’s description of transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness, acting as a stimulus for the observer to commence or continue one or more of the contemplative practices which foster them;

- the observer’s previous experience of transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness leading to their recognition of an artwork as contemplative;

- the artwork fostering transpersonal/contemplative states of consciousness in the observer;

- the artistic activity itself being a contemplative practice in its own right.

Significantly, by this rationale, contemplative art has been defined from a nondual perspective. This is in stark juxtaposition to the lens of conventional Art Theory, which would most likely, if not invariably, define it from the perspective of dualistic thinking. It is important for the reader to note that ultimately this nondual definition can only be verified through their own contemplative experience or the contemplative experience of others they trust, and not via enquiry related to philosophy, theology or conventional academic Art Theory based on dualistic thinking. This is so because contemplative art is known through the “Eye of Contemplation”, not the “Eye of the Mind” or the “Eye of the Flesh”.

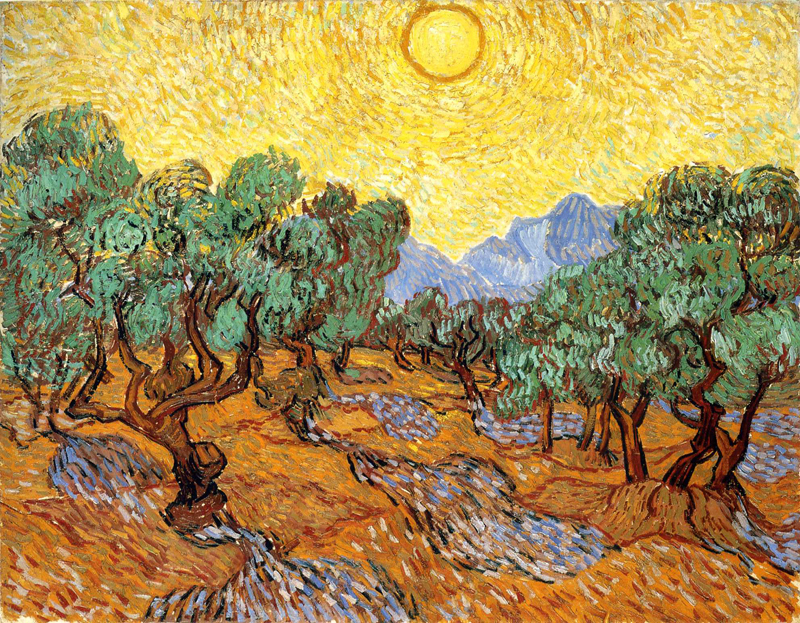

Photograph: Public Domain

Concluding remarks

As suggested by the blog’s subtitle, Sensing and knowing the ineffable nature of Divinity through contemplative art, contemplative art has profound implications for humanity. The ineffable nature of Divinity is apprehended directly when one abides in nondual contemplation. Hence, all that is to be gained by humanity in coming to sense and know its nature is accessible via nondual contemplation and the meditation and contemplative prayer practices facilitative of it. It is also accessible by the way the spiritual fruit of these practices can influence the creation and appreciation of contemplative art; potentially alter the very sense of being of the artist and the observer of the artwork, and thereby make palpable and visceral the ineffable nature of Divinity. For these reasons, of the myriad gifts bestowed on humanity by the Arts, contemplative art is unquestionably Supreme.

The reader, be they an artist or an observer of art, will gain optimum benefit from this gift, by pursuing contemplative practices such as meditation or contemplative prayer in a diligent and sustained manner, with the ultimate aim of abiding continuously in nondual contemplation, which is the Divine Ground of Being and the Primordial State of naked and choiceless awareness that is ever-present within them. As this state of consciousness is the reader’s ever-present inherent nature, contemplative art will not change them per se. Rather, it has the function of changing their perspective from an exclusive identification with their “ego”, to nondual contemplation, which both transcends and is immanent in all things perceived.

Consequently, and ironically, while contemplative art is the supreme gift of the Arts, it will not give the reader anything that they do not already have. Nonetheless, being one of the principal keys to the ineffable nature of Divinity, contemplative art has the potential to bring the reader home to their Divine Self, their Real Self, their Real Nature, and hence awareness of who they really are!

This outcome was beautifully expressed by the thirteenth-century Sufi contemplative poet, Fakhreddin Iraqi:

Beloved, I sought you

here and there,

asked for news of you

from all I met;

then saw you through myself

and found we were identical.

Now I blush to think I ever

searched for signs of you.By day I praised You

but never knew it;

by night I slept with You

without realizing;

fancying myself

to be myself;

but no, I was You

and never knew it.

o0o

This blog is a highly condensed version of an extensively researched and referenced essay by the same name, which is in turn an extension of and companion work to another extensive essay by the author titled, Mysticism, the Perennial Philosophy and Interfaith Dialogue. The way in which nondual contemplation (as described by the mystics of the various Wisdom Traditions) allows us to fully sense, know and thereby understand the ineffable nature of Divinity is more extensively explored in these longer essays. These essays are free and available from the author [contact the Editor for more details]. For recommendations on commencing or deepening contemplative practice, the reader is referred to the author’s essay, Mysticism, the Perennial Philosophy and Interfaith Dialogue.

Post Notes

- SoSAFE!

- Philip Brown: Transcendence through Beauty in Art & Nature

- Fakhruddin ‘Araqi: Divine Flashes

- Philip Brown: Mysticism and Mystic Experience

- Thomas Merton: The Statues of Polonnaruwa

- Julian Schnabel: At Eternity’s Gate

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- Philip Jacobs: Dance of the Dervishes

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Nature

- Hermann Hesse: The Journey to the East

- Walt Whitman & Jan Kersschot: The Body Electric