Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

An ascension to the Wordsworthian

Peter Donnelly graduated with a B.A. (International) and an M.A. in English from University College, Dublin. In 2010, he began to publish poetry in journals across Ireland and within UCD, where he won the Undergraduate Poetry Award. His first collection, Photons, was published by Appello Press in 2014.

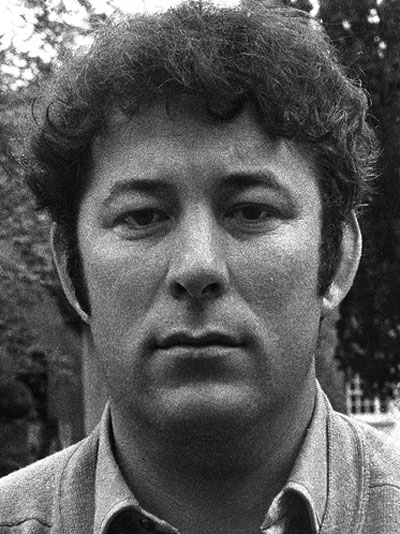

In this week’s guest post for The Culturium, Peter discusses the intimate parallels between the poetry of William Wordsworth and Seamus Heaney.

“As you plaited the harvest bow

You implicated the mellowed silence in you

In wheat that does not rust”

“THE HARVEST BOW”, which was included in Field Work (1979), the fifth collection of poetry by the Irish Nobel Laureate, Seamus Heaney (13th April 1939–30th August 2013), is a highly Wordsworthian master lyric of bucolic remembrance, which displays serene metrical control and imaginative fecundity; and, indeed, it might not be an exaggeration to hypothesize that the Cumberland-born poet would have been proud to put his own name after it.

If we consider Dante a kind of custodian spirit of Heaney’s preceding collection, North (1975), then it might be apt to conceive of Wordsworth’s corpus as playing a similar undercurrent, guardian angel role in Field Work, as it is a Wordsworthian energy, which allows the natural and the textual to coexist symbiotically, and register and electrify one another with vitality and signification. The poems in the collection possess a kind of almost organic magnificence and technical perfection that point, above all, to one thing—the artist as the finished article—that with which we, as an audience or as readers, always seek to come into contact.

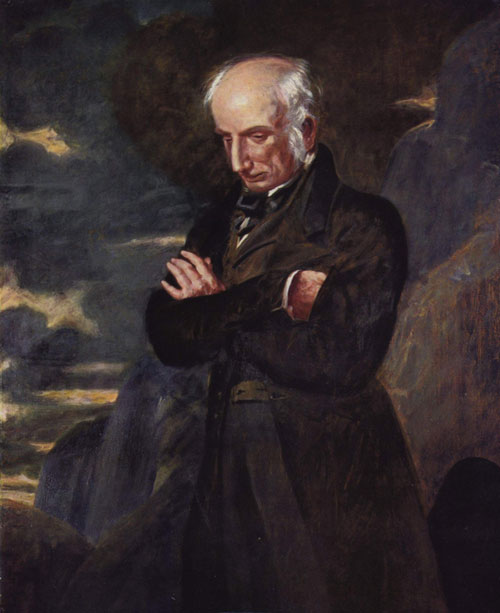

The Romantic poet, William Wordsworth’s unspoken ghost is a benign, haunting presence in Field Work: the spirits of pieces such as “Lines Written on Tintern Abbey” and “The Solitary Reaper” (not to mention The Prelude) pervade it, and are appropriated sublimely. Formally speaking, “The Harvest Bow” matches “Daffodils” in that it is made of six-line stanzas, of which each is composed of three couplets. Imagistically, as well as in terms of sentiment, Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” lines:

wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

—William Wordsworth, “Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey”, ll. 19–20

are echoed in “The Harvest Bow”’s:

Blue smoke straight up, old beds and ploughs in hedges

—Seamus Heaney, “The Harvest Bow”, l. 16

Photograph: [CC BY 3.0] Wikimedia Commons

More centrally, observation and observance of a subject’s inwardness revealed through the plying of a pastoral, solitary craft is a factor the two poems share. Time-honoured processes are vehicles through which the richness of inner being is opened up. The speakers of both poems are quasi-transfixed with a sort of awe: compare Wordsworth’s third-person:

Whate’er the theme, the Maiden sang

As if her song could have no ending;

I saw her singing at her work,

And o’er the sickle bending;—

I listened, motionless and still;

—William Wordsworth, “The Solitary Reaper”, ll. 25–29

With Heaney’s second-person:

As you plaited the harvest bow

You implicated the mellowed silence in you

In wheat that does not rust

But brightens as it tightens twist by twist

Into a knowable corona,

A throwaway love-knot of straw.

—Seamus Heaney, “The Harvest Bow”, ll. 1–6

The process of art-making itself is necessarily, inevitably part of the cognitive and metaphorical machinery at work in both poems: lines do indeed brighten into tightness and then set off against the following line as the poetical process interweaves and slubs. But the addressee of “The Harvest Bow” is a single person, and not mankind (or whoever happens to listen in), as is the Romantic register, and, as it so happens, that of the Lake poet in this instance. Heaney in this case broaches the terrain, whether consciously or not, of a sonnet; and indeed it is a love poem of sorts, though for a father or father figure and not an object of romantic affection. He writes:

Me with the fishing rod, already homesick

For the big lift of these evenings, as your stick

Whacking the tips off weeds and bushes

Beats out of time, and beats, but flushes

Nothing: that original townland

Still tongue-tied in the straw tied by your hand.

—Seamus Heaney, “The Harvest Bow”, ll. 19–24

The Poetry of Illusion and Paula Marvelly, La Mer

Indeed, one finds the term “tongue-tied” in Shakespeare (“My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still”, Sonnet 85). In Shakespeare and Heaney alike, in this sense, the mute inspiration is the ostensible driving force behind the enterprise of writing and embodies the mysteriousness behind it.

Furthermore, the intimacy of having a single addressee grants the reader a sense of a kind of licensed trespassing into someone else’s personal world, which is among the hallmarks of the sonnet within the Anglophone and Italian traditions— “private words addressed to you in public”, as T. S. Eliot termed it. Wordsworth, comparatively, loved the notional combination of pastoral work and singing (consider, for example, “from those loftiest notes / Down to the low and wren-like warblings, made / For Cottagers and Spinners at the wheel”, in The Prelude).

The respective closing couplets of “The Solitary Reaper” and the “The Harvest Bow” share a certain sentiment of memory reawoken and frozen in the present moment of thought; they both gather the emotional cataract that has preceded them and attempt to harness this into permanence and conclusion. Each finishing up with a “great lift”, the former’s final stanza reads (italics mine, though not “The end of art is peace” ):

I saw her singing at her work,

And o’er the sickle bending;—

I listened, motionless and still;

And, as I mounted up the hill,

The music in my heart I bore,

Long after it was heard no more.

—William Wordsworth, “The Solitary Reaper”, ll. 27–32

and the latter’s:

The end of art is peace

Could be the motto of this frail device

That I have pinned up on our deal dresser—

Like a drawn snare

Slipped lately by the spirit of the corn

Yet burnished by its passage, and still warm.

—Seamus Heaney, “The Harvest Bow”, ll. 25–30

Photograph: The Yorck Project, [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

The splendorous finish of “The Harvest Bow” transports him to the echelon of Wordsworth and of Heaney’s compatriot W. B. Yeats. In this, he passes, almost incontestably, beyond writers of the rural, which influenced his oeuvre such as Patrick Kavanagh and Ted Hughes, whose gifts he quite obviously exceeds, as talented as these poets were.