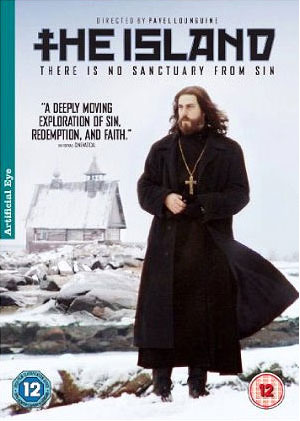

Pavel Lungin, The Island

There is no sanctuary from sin

“Wash me and I shall be whiter than snow.”

IT IS HARD to imagine how the likes of the greatest filmmakers of all time—Andrei Tarkovsky, Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson—would ever be seen again on the silver screen and yet to my utter delight, The Island (Ostrov), a tale of remorse and redemption, manages to embody the most perfect and elevated fusion of aesthetic sublimity with spiritual testament that I have ever seen in recent years.

Directed by Pavel Lungin (also known as Pavel Lounguine, born 12th July 1949), the film is the heartbreaking portrait of a man broken by guilt for a heinous act he was forced to commit, living out his days in a remote Russian Orthodox monastery in penance for his sin.

Shot in stunning monochromatic shades of blue and grey as if the very celluloid itself were etched from panes of ice, The Island is an epiphanic homage to the enduring power of the human spirit and its relationship to the Almighty Lord.

Photograph: © 2017, Curzon Artificial Eye

The film opens to the sight of a man rowing a small boat through an inky seascape, the sound of wind and wave and the exquisitely composed soundtrack by Vladimir Martynov lapping against our ears and lulling us into an uneasy trance.

Then on shore, walking purposefully over rock and tundra, we hear him muttering the Jesus Prayer without ceasing in sequence with the pace of his feet:

Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God …

Like the anonymous nineteenth-century pilgrim who travelled across Russia in search of peace of mind inspiring J. D. Salinger’s novella of a young woman’s spiritual awakening in Franny and Zooey, this ghostly shadow of a man, driven by his restless, tormented spirit, will take us on a profound inner journey to the very heart of what it means to live a moral life.

Photograph: © 2017, Curzon Artificial Eye

We are then shown a vision of hell. It is World War II and our protagonist, Anatoly, is working as a stoker on a Soviet cargo boat containing a shipment of coal, which is captured by the Nazis. Forced to shoot his captain, Tikhon, in exchange for his own life, the ship is then blown up and Anatoly is thrown into the sea. Miraculously, he survives and is found by monks shortly afterwards, washed up on a nearby shore.

Fast forward to 1976, Father Anatoly now lives as a renunciate in a monastery, working in the boiler room and offering, albeit reluctantly, spiritual counsel and medical advice to those who visit him—a pregnant woman seeking his blessing for an abortion; a distraught widow not knowing how to process her torment; a young boy with crippled legs wanting physical relief. For word has got around that he is a soothsayer and mystic, blessed with the power of prophecy and the healing of hands.

And yet, the Holy Father resembles more a “holy fool” (jurodstvo or “foolishness for Christ” practised by Eastern Orthodox ascetics) with his eccentric behaviour, deliberately mocking and chastising his fellow flock for their hypocrisy and vainglorious faith. In a particularly poignant scene, he educates the abbot, Father Filaret, about his attachment to earthly possessions, whereby he burns his favourite books in the furnace, jettisons his treasured blanket into the lake and nearly chokes him to half to death whilst locked in the boiler room, reminiscent to an abysmal cycle from Dante’s Inferno.

Photograph: © 2017, Curzon Artificial Eye

Father Anatoly’s religious conviction provokes envy in his brother hieromonk, Father Job, who persistently tries to undermine his eminence and yet Father Anatoly’s own conscience is the very root cause of his prolonged suffering—that he has killed a man and must forever carry the burden of guilt.

Indeed, in spite of his good deeds, he often wanders the hyperborean scrubland, decrying his outcast state and begging God for mercy and forgiveness. The beautiful cinematography, with Tarkovskian closeups of shrubs and spume and verglas, reiterates the cruel and chilling beauty of living an existence permeated with psychological anguish.

As the film nears its finale, a Soviet ship’s admiral visits the island with his insane daughter, who, exhibiting demoniacal behaviour, cackles like a hen, to which Father Anatoly similarly responds atop the monastery’s bell tower, à la Andrei Rublev. In a deeply moving balletic segment set amidst the surrounding snowy-white wilderness, he exorcizes her demons by humbly praying to God and she is instantaneously cured.

Photograph: © 2017, Curzon Artificial Eye

The final twist to The Island brings the film to a satisfying, albeit neat, conclusion, giving meaning to Father Anatoly’s suffering as he delivers his final line, “Lord, receive my sinful soul”, the closing scene repeating the opening leitmotif of a boat traversing the sea, symbolizing the passage from sin to salvation, ignorance to wisdom, wretchedness to peace.

Indeed, the whole experience of watching Pavel Lungin’s exquisite masterpiece is to be drenched in a baptismal cleansing of our own, reiterating the revelatory and transcendental nature of cinematic art to enrich and enlighten its audience.

In his seminal text, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema, Andrei Tarkovsky outlines his own vision of the creative muse, one from which no doubt Pavel Lungin took heed and embraced within his own work:

Before going on to the particular problems of the nature of cinematic art, I feel it is important to define my understanding of the ultimate aim of art as such. Why does art exist? Who needs it? Indeed, does anybody need it? These are questions asked not only by the poet, but also by anyone who appreciates art […]

Photograph: © 2017, Curzon Artificial Eye

In any case it is perfectly clear that the goal of all art […] is to explain to the artist himself and to those around him what man lives for, what is the meaning of his existence. To explain to people the reason for their appearance on this planet; or if not to explain, at least to pose the question […]

Again and again man correlates himself with the world, racked with longing to acquire, and become one with, the ideal which lies outside himself, which he apprehends as some kind of intuitively sensed first principle. The unattainability of that becoming one, the inadequacy of his own ‘I’, is the perpetual source of man’s dissatisfaction and pain.

And so art, like science, is a means of assimilating the world, an instrument for knowing it in the course of man’s journey towards what is called ‘absolute truth’ […] Art is born and takes hold wherever there is a timeless and insatiable longing for the spiritual, for the ideal: that longing which draws people to art.

Post Notes

- Curzon Artificial Eye: The Island

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Xavier Beauvois: Of Gods and Men

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- J. D. Salinger: Franny and Zooey

- Spiros Stathoulopoulos: Meteora

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- Robert Harris: Conclave

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates

- Gospel of Mary Magdalene

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora

- Kim Ki-duk: Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

- Carl Theodor Dreyer: Ordet

- Lisandro Alonso: Jauja

- Victor Kossakovsky: Gunda + Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier: The Velvet Queen