Voices of visionary women on power and belief

What is meant by ‘reality’? It would seem to be something very erratic, very undependable—now to be found in a dusty road, now in a scrap of newspaper in the street, now a daffodil in the sun. It lights up a group in a room and stamps some casual saying. It overwhelms one walking home beneath the stars and makes the silent world more real than the world of speech—and then there it is again in an omnibus in the uproar of Piccadilly. Sometimes, too, it seems to dwell in shapes too far away for us to discern what their nature is. But whatever it touches, it fixes and makes permanent. This is what remains over when the skin of the day has been cast into the hedge; that is what is left of past time and of our loves and hates. Now the writer, as I think, has the chance to live more than other people in the presence of this reality. It is his business to find it and collect it and communicate it to the rest of us.

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

PAULA MARVELLY, creator and editor of The Culturium, has spent many years writing about spirituality, culture and the arts. She has a BA (Hons) degree in English from the University of London and an M.Phil research degree in European Studies from the University of Cambridge. She is also a published author and filmmaker. You can browse her work on Amazon, IMDb, Vimeo and YouTube.

It is with immense pleasure and gratitude that a book I wrote nearly 20 years ago has been reissued by Watkins Publishing (June 2024), completely revised with an additional chapter on British novelist, Virginia Woolf. The beautiful cover artwork is designed by Francesca Corsini and the audiobook is compellingly narrated by award-winning British actor, Polly Lee.

In our contemporary culture when even definitions of what constitutes being a woman itself are being called into question, The Sacred Feminine Through the Ages returns to the beginning of recorded history in order to re-examine how attitudes towards women and the female principle have changed throughout the centuries up to modern times.

Starting with the emergence of written glyphs and symbols known as cuneiform, we embark upon an anthological journey comprising poetry, prose, diary entries and letters from the diverse cultures, ethnicities and spiritual traditions of the world—Indigenous, Jewish, Christian, Sufi, Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist—giving voice to an array of female protagonists, both mythological and flesh and blood reality, together with charting their agonies and ecstasies along the spiritual path.

Our first port of call is the empire of Mesopotamia and the priestess Enheduanna, whose literary supplications to the moon goddess Innana make her the first recorded writer in history. Next, to ancient Egypt where the formidable pharaoh Queen Hatshepsut’s rule was almost obliterated from the records of antiquity by her male counterparts. Then, to India and the wise ruminations of female sage Vak, whose immortal words graced the likes of Vedic scripture, the oldest religious texts known to mankind.

The illustrious Queen of Sheba subsequently takes centre stage with her impassioned proclamations about the nature of wisdom. Next, the Lesbian poet Sappho with her heartfelt musings on sexual desire and devotion to the goddess of love. Then, the mother of the Buddha, Mahapajapati, and her protestations to be allowed into the Buddhist sangha, something her enlightened son was, rather surprisingly, initially reticent about.

Later, we read of Mary Magdalene, whom Jesus allegedly loved more than any other of his disciples, as well as the divinely inspired confessional literature of German abbess Hildegard of Bingen, English anchorite Julian of Norwich and Spanish Carmelite Teresa of Avila, friend and compatriot of St John of the Cross. Finally, we engage in an appraisal of the transcendental poetry of Emily Dickinson, the soul-searching diary entries of Sufi Irina Tweedie and the literary fervour of doyenne of the feminists Virginia Woolf.

Scattered among these illustrious women are the female deities who have shaped our mythological inheritance—the goddess of creativity Saraswati from India, the goddess of compassion Kuan-yin from China, the goddess of beauty Aphrodite from ancient Greece—forming the metaphysical foundations of world history through their inspirational words.

In a time period when the number of living female role models in our contemporary society is significantly wanting, reviving attention towards lost and misunderstood women, as well as celestial beings from the past, could not be more urgent or timely.

That said, Virginia Woolf reminds us in her concluding remarks of the book’s passage through the annals of literature that despite profiting from the heartfelt cries of our forebears, it is vital we also retain the ability to think for ourselves and remain as authentic as possible. Indeed, our life’s work should be to investigate reality and the very nature of self by embracing our divine inheritance and embodying our feminal soul.

Here I would stop, but the pressure of convention decrees that every speech must end with a peroration. And a peroration addressed to women should have something, you will agree, particularly exalting and ennobling about it. I should implore you to remember your responsibilities, to be higher, more spiritual; I should remind you how much depends upon you, and what an influence you can exert upon the future […] When I rummage in my own mind I find no noble sentiments about being companions and equals and influencing the world to higher ends. I find myself saying briefly and prosaically that it is much more important to be oneself than anything else …

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Post Notes

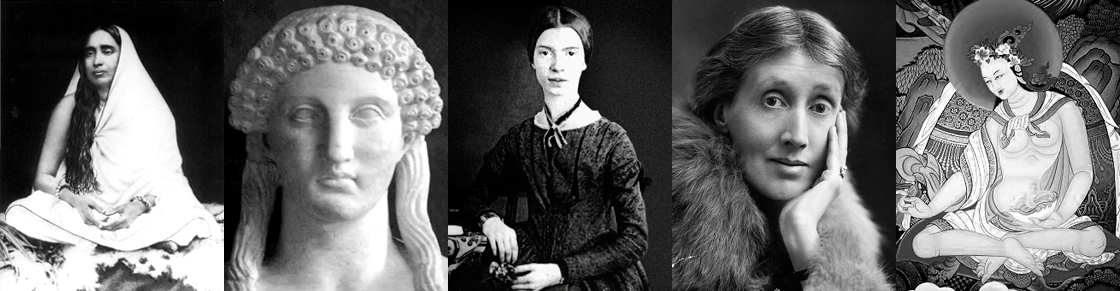

- Feature image: Sarada Devi, Sappho, Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, Yeshe Tsogyal,

Public Domain - Watkins Publishing

- Polly Lee

- Francesca Corsini

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Kathleen Raine: The Land Unknown

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Pocket Canons Bible Series

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme