Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

In search of the miraculous

Gloire à l’Esprit de Dieu!

Glory be to the spirit of God!

IT IS DIFFICULT to imagine as I stand, gazing up at the Sanctuaire Notre-Dame de Laghet, that just over the brow of the hill, the grande corniche meanders its way down to Monaco, where man’s hedonistic achievements—gambling casinos, Formula One racing tracks, super yachts—pay homage to all that is Mammon. And yet here at the foot of the sanctuary, a Provençal château sitting atop a promontory in the south-eastern French valley region of Alpes Maritimes, it is not man’s accomplishments that are worshipped but the grace and glory of God.

For in 1652, it was reported that the Virgin Mary had manifested, not through her visible presence but the spontaneous healing of the sick and dispossessed. When news started to circulate that miracles were being performed in the Chapel of Laghet, visitors and believers were soon coming from not only every compass point of France but from all parts of the Catholic world. Now, Notre-Dame de Laghet has a reputation rivalled only by Lourdes and Rome as a place of divine deliverance for the physically and mentally infirm.

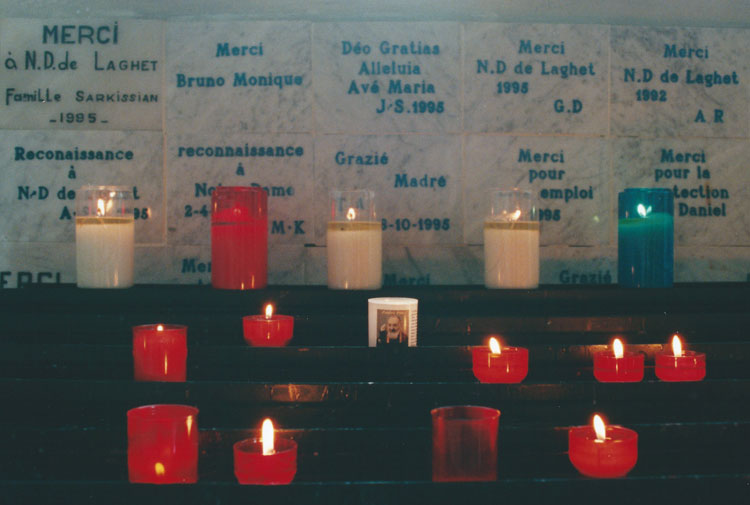

Somewhat intrepidly, I cross the threshold of the front porch of the church before entering into an arcade. A cavalcade of candles, encased in small red, blue and opaque plastic containers of varying price and size are here to greet me, haemorrhaging a heat more intense than the Mediterranean climate I’ve just left outside.

In a holy place, how much financial offering you make suddenly takes on a new type of currency—a 3-franc candle seems too agnostic; a 15-franc candle possibly a little too devout. I settle for a 5-franc candle and deposit a silver piece into a dark slit in the wall, where a plaque politely reminds me of the profound importance of lighting a votive gift:

Que le flamme de ce cierge brûle pour Toi, Seigneur.

May this flame burn for you, Lord.

The virgin wick of my candle touches a flame; it splutters momentarily and then I place it amidst all the others where, in all its trembling golden glory, it joins the devotional dance. I watch in awe and start momentarily to wonder whether I really should have bought the 15-franc candle instead.

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

And yet traditional Catholic iconography is not the main theme here—this is a sanctuary devoted to the survivors and victims of tragic accidents: car, train and plane crashes; industrial negligence; fatal disease. With poignant, cartoonesque simplicity, pencil and crayon drawings and pastel watercolours of patients lying in sick beds being blessed by a vision of the Virgin Mother jostle for our sympathy. And jigsawed between the frames are messages of gratitude etched into the very wall—one in particular, outlined by a love heart, implores, “Protégez ma famille”. I stand and bear witness to a concatenation of suffering and faith.

The smooth granite floor, polished by the feet of thousands of pilgrims, nuns and tourists, leads me through the colonnade. There is an exhibition on martyrs, which decorates the way.

Faire memoire des martyrs de la fois 20 siècles.

In memory of the martyrs of faith over the past 20 centuries.

For every century, a Romanesque banner glorifies those who have lost their lives …

20ème siècle: Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Sainte Maria Goretti

19ème siècle: Saint Pierre Chanel, Saint Charles Lwanga

18ème siècle: Les Bienheureuses Carmélites de Compiègne

17ème siècle: Saint Isaac Jogues

16ème siècle: Saint Paul Miki et ses compagnons …

Jesuit, Franciscan, Benedictine nuns, monks and priests persecuted for their belief …

15ème siècle: Saint John Fisher, Saint Thomas More

14ème siècle: Bienheureux Gentil

13ème siècle: Saint Othon

12ème siècle: Thomas Becket

11ème siècle: Saint Stanislas …

Missionaries and emissaries assassinated for their trust …

10ème siècle: Saint Venceslas

9ème siècle: Saint Edmund

8ème siècle: Saint Boniface

7ème siècle: Saint Maxime le Confesseur

6ème siècle: Saint Joan 1er. …

Crucified by man, canonized by the Catholic Church …

5ème siècle: Saint Félix, Saint Cyprien

4ème siècle: Sainte Félicité, Sainte Perpétue

3ème siècle: Saint Côme, Saint Damien

2ème siècle: Saint Pothin, Sainte Blandine

1er siècle: Saint Étienne

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

“Est-ce que vous avez un guide en anglais?”

“Oui, oui.”

Her movements are graceful and without effort as she searches for an English brochure. I am transfixed by her. She seems to embody a contentment and containment I have rarely seen in a woman. Despite being swathed in white robes, there is an ineffable elegance about her, a sacred femininity that defies convention, rendering me mute.

She then says something I cannot quite understand but the turn of her eyes towards heaven is enough to make me appreciate that she is asking me whether I believe. My French being woefully inadequate to enter into a discussion about my take on the meaning of existence, I enthusiastically nod. The sister is delighted.

“Tomorrow, you come to Vespers?”

It is twenty past six the following evening. The sky is azure blue and the cool breeze caressing the courtyard in front of the church is a welcome relief. Groups of people cluster expectantly under the shade of walnut trees, as children skip and hopscotch and laugh. The faint sound of a mediaeval melody starts to filter through the grilled windows of the chapel—as I strain to listen, the animated, guttural conversation around me starts to become an irritating dirge.

The clock tower bell announces office du soir, evening service, at half past six and we all file reverentially into the church, passing through the outer cloister into the inner chapel. As my eyes adjust to the darkness, it is as if I am entering another world, where my problems no longer exist and peace reigns forever in my heart.

I sit down on a pew towards the back, next to a burly couple shushing their restless children. An elegantly dressed woman strides in along the aisle and then nestles in front of me, a miasma of Chanel and cigarette smoke, like a profane perfume in this sacred place. Statues of Sainte Therese, Sainte Bernadette, Sainte Jeanne d’Arc and the Virgin Mary, all quietly regard the congregation with abject resignation and nonchalance.

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

In turn, each sister bows gracefully in front of the altar and then takes up her place in the chancel. One sister sits in front of an electronic harp, laid flat to be played like a keyboard. With an eurythmic flourish from her fingers, the sisters burst into song, a polyphonic canticle, which sounds like a cross between Enya and Hildegard of Bingen.

I scan the nuns’ faces looking for the sister I spoke to yesterday in the gift shop and find her seated in the back row, her attention lost in rapture and benevolence. I start to feel envious of her utter absorption in her faith and reflect upon whether the eremitic life is the only way to find peace in this life.

The singing comes to an end and then through a loud speaker hidden somewhere amidst the Corinthian-style arches, a sister recites the evensong prayer. Dutifully, the congregation responds by chanting during the pauses.

Gloire à l’Esprit de Dieu!

Glory be to the spirit of God!

I mime with my lips, endeavouring to enter into the spirit of things. It has been years since I last went to church and vestiges of guilt and remorse course through my heart.

The exotic and antique words of the ceremony transmogrify themselves into a mysterious and melodious drone. The wafts of scents and smells unfamiliar—a heady concoction of incense, mould and piety—coupled with a late spring afternoon’s somnolence, lulls me into a hypnotic trance and I have to remain seated whilst the others follow the ceremonial drill of standing up and sitting down at the appropriate moment.

I feel oddly removed from the pageantry with all my senses saturated in religious rite. I am drowning in sea of synæsthesic overload. I close my eyes and die unto the temporal world.

I wake with a gasp. People are crossing their foreheads and chests; it is the end of the service. The sisters bow once more in front of the Virgin Mother and leave through the nave.

As everyone gathers their things, theatrically kissing each other on the cheeks, I loiter a while, regaining my equilibrium in this supernatural place. As I take my leave, I see my sister stacking away hymn books and music sheets. Again she is moving with the ease and grace and momentum of a dancer. I am in the presence of the Divine Feminine.

Tentatively, I approach, not wishing to interrupt her official duties. She looks around and seeing who I am breaks into a radiant smile.

“Vous êtres très belle,” I say.

“What you see comes from within.” She points to her chest. “That is God.”

She smiles once again and then returns to her chores.

Despite the imminent approach of sunset, as I step outside I still have to shield my eyes from the glare of the light. Perhaps that is why I have to blink away the tears.

And as I sit in my car composing myself in readiness to drive back in the direction of Monaco, the worship of wealth and fame only a few kilometres away, I wonder how can it be that an unnamed sister of Sanctuaire Notre-Dame de Laghet, through renouncing all earthly possessions, has in fact gained the only things worth having in this life—an open heart and peace of mind.

[Extract from unpublished notebook, circa 1995]

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

Post Notes

- Sanctuaire Notre-Dame de Laghet

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- The Spirituality of Duncan Grant

- Paula Marvelly: Sacra di San Michele

- Henri Matisse: Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence

- Jean Cocteau: Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora

- The Spirituality of Marc Chagall