Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

How a mountain became a painter’s creative muse

“The world doesn’t understand me and I don’t understand the world, that’s why I’ve withdrawn from it.”

ARUNACHALA IN INDIA. The Zhongnan Mountains in China. Mount Kailash in Tibet. All these peaks are synonymous with places of cultural and spiritual significance, bestowing peace and wisdom on all those who meditate upon them.

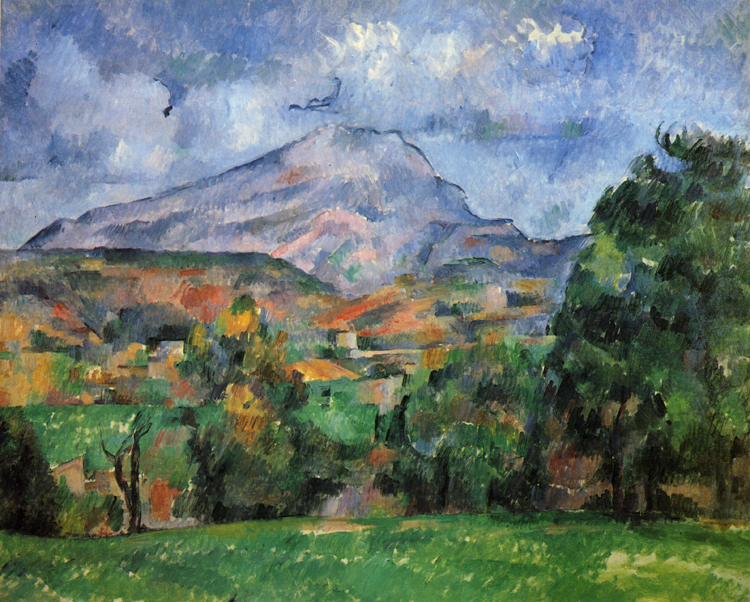

La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, situated in Provence in southern France, may not have the same global appreciation as other mountainous ranges and yet for the Post-Impressionism painter, Paul Cézanne, (19th January 1839–22nd October 1906), it became his creative muse.

Colour is the place where our brain and the universe meet. That’s why colour appears so entirely dramatic, to true painters. Look at Montagne Sainte-Victoire there. How it soars, how imperiously it thirsts for the sun […]

For a long time I was quite unable to paint Sainte-Victoire; I had no idea how to go about it because, like others who just look at it, I imagined the shadow to be concave, whereas in fact it’s convex, it disperses outward from the centre.

Instead of accumulating, it evaporates, becomes fluid, bluish, participating in the movements of the surrounding air.

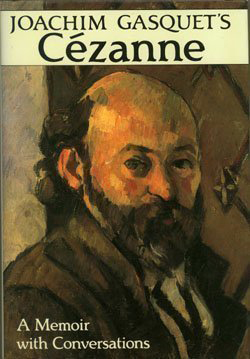

—Joachim Gasquet, Cézanne: A Memoir with Conversations

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

And yet despite the financial and fraternal support, the work of Paul Cézanne was ridiculed by art critics and the Parisienne bourgeoisie, as well as being repeatedly rejected from the illustrious Salon of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which all served to culminate in his eventual return to the Provençal region of his youth to work in near isolation effectively until his death.

I work obstinately, and once in a while I catch a glimpse of the Promised Land. Am I to be like the great leader of the Hebrews, or will I really attain unto it? […]

I have a large studio in the country. I can work better there than in the city. I have made some progress. Oh, why so late and so painful? Must art indeed be a priesthood, demanding that the faithful be bound to it body and soul?

—Ambroise Vollard, Cézanne

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Indeed, as his attention turned away from portraiture toward the beauty of nature, La Montagne Sainte-Victoire would become the focus of his intense and uncompromising gaze. Over the course of his later years, Cézanne would produce more than 44 oil paintings and 43 watercolours of the spectacular pinnacle of Provence, immortalizing his vision of the natural world.

Painting must give us the flavour of nature’s eternity. Everything, you understand. So I join together nature’s straying hands […] From all sides, here, there and everywhere, I select colours, tones and shades; I set them down, I bring them together […] They make lines, they become objects—rocks, trees—without my thinking about them […]

But if there is the slightest distraction, the slightest hitch, above all if I interpret too much one day, if I’m carried away today by a theory which contradicts yesterday’s, if I think while I’m painting, if I meddle, then whoosh!, everything goes to pieces.

—Joachim Gasquet, Cézanne: A Memoir with Conversations

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Coupled with the tempestuous relationship with his wife, Hortense, Cézanne withdrew evermore from all society to a studio (atelier) in Jas de Bouffan, a small village in the shadow of La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, in order to work in complete silence, free from all external pressure and criticism, availing himself to the mountain’s muse.

Art has a harmony which parallels that of nature. The people who tell you that the artist is always inferior to nature are idiots! He is parallel to it. Unless, of course, he deliberately intervenes. His whole aim must be silence. He must silence all the voices of prejudice within him, he must forget […] And then the entire landscape will engrave itself on the sensitive plate of his being.

—Joachim Gasquet, Cézanne: A Memoir with Conversations

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

A paean of paint honouring the glory of nature, Cézanne’s creations exult the arcadian panorama that is Provence. As La Montagne Sainte-Victoire rises up majestically and silently toward the sky in an opalescent rhapsody of blues and greens and golds, we partake of one of the greatest transmogrifications in the history of the visual arts.

Yes, a bunch of carrots, observed directly, painted simply in the personal way one sees it, [is] worth more than the Ecole’s [French Classical Art Academy] everlasting slices of buttered bread, that tobacco-juice painting, slavishly done by the book […] The day is coming when a single original carrot will give birth to a revolution.

—Joachim Gasquet, Cézanne: A Memoir with Conversations

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Indeed, observing the La Montagne Sainte-Victoire paintings is akin to partaking of a sacred rite, eliciting profound and transmutational feelings within, whereby the experiencer, the experienced and the very act of experiencing all merge into one.

Nature as it is seen and nature as it is felt, the nature that is there … [he pointed towards the green and blue plain] and the nature that is here [he tapped his forehead] both of which have to fuse in order to endure, to live that life, half human and half divine, which is the life of art or, if you will … the life of god.

—Joachim Gasquet, Cézanne: A Memoir with Conversations

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Post Notes

- PaulCezanne.org

- The Awakened Eye: Paul Cézanne

- Rainer Maria Rilke: Letters to a Young Poet

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Rashid Maxwell: To Save the Planet With a Paintbrush

- Jean Cocteau: Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer

- Henri Matisse: Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence

- Guy Laramée: Fraîcheur

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Mark Rothko: The Artist’s Reality