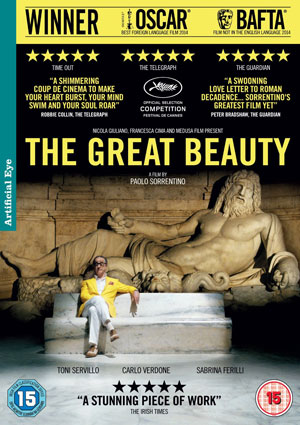

Paolo Sorrentino, The Great Beauty

Beauty is truth, truth beauty—that is all ye need to know?

“Travel is useful, it exercises the imagination. All the rest is disappointment and fatigue. Our journey is entirely imaginary. That is its strength. It goes from life to death. People, animals, cities, things, are all imagined. It’s a novel, just a fictitious narrative … You just have to close your eyes. It’s on the other side of life.”

—Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Journey to the End of the Night

IN THE TRADITION of Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte and Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, La Grande Bellezza (The Great Beauty), written and directed by Paolo Sorrentino (born 31st May 1970), is a meditation on one man’s search for intellectual and emotional fulfilment in the twilight of his life.

Jep Gambardella (played by Toni Servillo) is an ageing socialite bachelor, known by everyone who matters in Rome’s social elite. Having written a promising novel in his twenties, he now lives a comfortable life hosting elaborate parties and writing cultural columns for an arts magazine.

Then, out of the blue, he is visited by a stranger who brings him shattering news concerning someone from his past. Devastated, Jep goes for long walks amidst the streets and canals and ruins of his beloved Roman city, remembering forgotten friends and lost love.

Indeed, the film’s opening quotation, taken from Céline’s famous novel, forms the leitmotif for the entire movie, as he embarks on his nostalgic passeggiata.

Image: Janus Films

The way, the truth and the life

No longer forgiving or tolerant of untruths and hypocrisy, the catastrophic jolt to Jep’s decadent lifestyle endows him with the power of an unselfconscious directness, even in the company of his closest friends, a refreshing attribute for a writer more used to massaging facts to his advantage.

After a female companion pontificates about her life’s successes at a party, Jep finally interjects. Drawing deeply on his cigarette and expressing himself with all the sonority and charm that only an Italian can muster, he explains:

As we care about you, we don’t want to embarrass you … You know, all this boastful talk, all this serious ostentatiousness, ego, ego, ego … These harsh damning judgements of yours, hide a certain fragility, a feeling of inadequacy, and above all, a series of untruths …

Instead of acting superior and treating us with contempt, you should look at us with affection. We’re all on the brink of despair, all we can do is look each other in the face, keep each other company, joke a little … Don’t you agree?

Image: Janus Films

Beauty is truth …

Jep is experiencing life in a way he has never seen before. As he haunts the evening nightlife exuding vampiric elegance to the score of Górecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs (No. 3, Op. 36), beauty is everywhere, beckoning him with her sultry, mysterious eyes—a woman on a flight of steps who reminds him perhaps of someone he once knew; an ageing stripper in a friend’s exclusive nightclub dancing her youth away; a Muslim woman in a burqa, her eyelids thick with kohl. All have the power to fascinate him and yet he remains completely unmoved.

The Great Beauty reminded me of American Beauty, a film that explores similar concepts surrounding appearance, conformity and self-worth, as well as the main protagonist, Lester Burnham’s search for meaning and spiritual fulfilment.

And yet whereas Sam Mendes’ film invites us to discover beauty in the mundane and every day—a plastic bag dancing in a flurry of wind—Sorrentino presents us with a man, as in Dante’s La Vita Nuova, who has had a glimpse of the Great Beauty herself only for her to evade him continuously until the very end of his days.

Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Roma.

Image: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

… and truth, beauty

The Great Beauty is exquisitely shot, with panoramic views over the River Tiber and its bridges, along with candlelit tours of imposing galleries and palaces, making the city an integral character in the drama. Coupled with the sumptuous original musical score by Lele Marchitelli, we feel we are watching a magnificent opera, with our senses saturated in opulence.

Indeed, at the beginning of the film, a Japanese tourist collapses after taking architectural photographs, with the implication perhaps that he has become afflicted with Stendhal Syndrome, a psychosomatic disorder triggered by aesthetic overload.

The theme of writing is also a recurrent motif: Fyodor Dostoyevsky, André Breton, Gustave Flaubert and Marcel Proust are all mentioned in passing—a quote here, a joke there, elevating the film’s artistic vision ever higher.

In the final sequences, Jep’s own writing career is also brought back into focus. In a truly surreal scene, Sister Maria, a saint and admirer of his work, is drinking coffee on Jep’s penthouse terrace overlooking the Colosseum, surrounded by migrating flamingoes. She asks him why he didn’t write another book. “I was looking for the great beauty but didn’t find her,” he wistfully replies.

Image: Janus Films

This is all ye need to know

In the elegant and poignant final moments, Jep reflects on his past and the Beatific Vision, that glimmer of truth he once beheld, if only for a moment:

This is how it always ends … with death. But first there was life, hidden beneath the blah, blah, blah … It is all settled beneath the chitter chatter and the noise. Silence and sentiment. Emotion and fear. The haggard, inconstant splashes of beauty, and then the wretched squalor and miserable humanity. All buried under the cover of the embarrassment of being in the world. Beyond there is what lies beyond. I don’t deal with what lies beyond. Therefore let this novel begin. After all, it’s just a trick. Yes, it’s just a trick.

Echoing Céline’s words, he knows that even the beauty of Rome cannot save him. And therein lies the tragicomedy, which we must call life.

The film ends with its credits superimposed on an extended, languorous sequence taken from a boat sailing up the Tiber to the accompaniment of a strings version of Vladimir Martynov’s The Beatitudes by the Kronos Quartet. It is as if the film cannot let us leave the auditorium just yet, endeavouring to seduce us one last time with all its beauty and grandeur until it finally relinquishes its spell over us and fades into black.

Post Notes

- Robert Harris: Conclave

- Joel Coen: The Tragedy of Macbeth

- Satyajit Ray: Charulata

- Abbas Kiarostami: Certified Copy

- Scott Guyon: Why Beauty Matters

- Ansel Adams: The Search for Beauty

- Rollo May: My Quest for Beauty

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Michelangelo Frammartino: Le Quattro Volte

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates