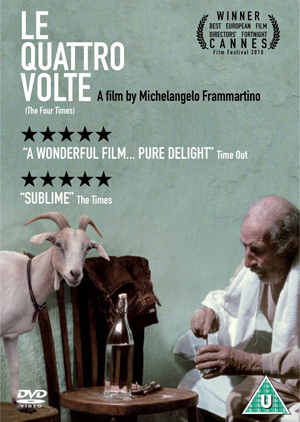

Michelangelo Frammartino, Le Quattro Volte

A meditation on the fragility of life

“For me, it’s a film about the connection between mankind

and the world and the things that are around us.”

—Michelangelo Frammartino

LA VITA CONTEMPLATIVA has always been extolled by poets and philosophers alike for the sheer fact that it brings us back in touch with our innermost being. And yet this is not necessarily a retreat into eremitic orders or religious seclusion; rather, it can be the simple life of a Calabrian peasant coming to terms with the fragility and finality of his life.

Set in the remote mountain town of Caulonia in southern Italy, Le Quattro Volte (The Four Times) by Italian director Michelangelo Frammartino (born 1968) is a poetic meditation on the theory of metempsychosis propounded by the Greek thinker, Pythagoras, regarding the four cycles of existence.

Image: © Kino Lorber Films

Le Quattro Volta is a phrase used by Pythagoras, or attributed to Pythagorus … It’s used in this way: we humans have, within ourselves, four successive lives, each one enclosed inside another. And so we are minerals because our skeleton is made of salt, of mineral substances, but we are also vegetables, plants, because our blood is like sap and we reproduce. We are animals because we have movement, knowledge of the world around us, memory, but we are ultimately rational beings. We are four things and to know ourselves completely we must know ourselves four times. So these are the four times, this is our journey.

—Michelangelo Frammartino

Tracing the metaphorical passage of one goatherd’s spirit as it passes from human embodiment to animal (a goat kid) to vegetable (a tree) to mineral (a charcoal kiln), Le Quattro Volte explores the interconnectedness of all manifested phenomena.

Presented through mesmerizing cinematography and enchanting ambient sound—the rustling of leaves, the clanging of bells, the bleating of goats—Frammartino’s masterpiece is an utterly beautiful and beguiling cinematic contemplation on the theory of the fourfold transmigration of souls.

Image: © Kino Lorber Films

This ritual is a dialogue or an exploration of the relationship between man and nature. We are made of the same material. I want to explore this strong connection. We are in a big technological period but this, perhaps, is why we’re feeling a need to be more connected. But perhaps we also consider ourselves, humans, as too important, and this is a way of showing how we can reconnect with the natural world around us, or the non-human world more precisely. In most cinema, only humans can be the main character or characters. But I want to find my protagonist in a tree or a mountain and want to be able to express this in a strong way.

—Michelangelo Frammartino

The first phase of Le Quattro Volte bears witness to an ailing goatherd, who is suffering from a severe chest infection. In order to alleviate his symptoms, he drinks a darkly nightcap remedy, which we soon discover comprises the dust swept up from the floor of the local church. We are simultaneously appalled and feel pity for his humble faith in medicating himself with this divine detritus, which paradoxically is probably the very cause of his complaint.

Indeed, as the film itself is without narration or dialogue, the elements of nature personify many of the dramatis personae, not least the motes of dust that murmurate through the chapel’s atmosphere, foreshadowing the goatherd’s death and that to which he shall return.

Image: © Kino Lorber Films

Over time I have become convinced that the movie camera is a tool that has a much less clear-cut role than we imagine. It is not simply a tool for reproducing reality but I feel it is a tool with the ability to perceive, to capture, to film the bond between man and nature, that invisible thing that is in between.

—Michelangelo Frammartino

The second, and probably most poignant phase, concerns the animal realm and in particular, the birth of a baby white goat. Apparently, the director spent two years observing the behaviour of these caprine creatures in order to understand and pre-empt their bodily movements.

And it was definitely worth it, for the camera is able to encapsulate the comedy and characteristics of the Calabrian herds, with the fate of one baby goat pulling at our heartstrings as he becomes separated from his mother and wanders the countryside in pursuit of her protection.

Image: © Kino Lorber Films

What I care about is to take back what we had: a healthy relationship with what is around us. This is really a vital aspect for me. This act of ‘taking back’, however, is not to be confused with possession: it resembles more a feeling of connection with nature, the re-establishment of a deep bond with it, which could allow us to perceive ourselves again as part of Everything and to grow a new, universal kind of love that broadens to include everything that surrounds us.

—Michelangelo Frammartino

Phase three is the study of the plant realm in the form of a fir tree, which is felled and erected in the town square as part of a cultural celebration, surrounded by the local villagers in a state of joy and merriment. This leads naturally to the fourth and final mineral phase involving the chopping up of the fir tree into logs in preparation to be made into charcoal kilns, the smouldering embers forming the first and last sequences of the film.

The last shot comprises the wisps of smoke gently wafting out of a chimney pot and, like the goatherd’s dusty infusion, points to the fact that all of life is inextricably linked through the very carbon molecules of each and every human, animal, plant and mineral’s DNA.

Image: © Kino Lorber Films

I have to admit that recently I’ve not been thinking about religion, but it is something I had reflected upon for a long time, also during the shooting. I had an anticlerical and irreligious education: the small village where I lived hosted, during the war, one of the few communist upheavals of Southern Italy. My family has been historically linked to communism, and perceived the Church as an opponent. Religion was really seen as a futile ‘opium of the people’, and I often looked down on believers.

Yet, as time went by, I came to meet faith, the invisible and the transcendent, along my artistic path. I wanted to face these complex issues, trying to abandon my juvenile prejudices. Even though I never got close to any religion, in my movies, there is a huge interest in and respect towards those who believe: my intent is to get in touch again with faith in its original sense, meant as the uplifting of the spirit towards transcendence. Also the ‘animism’ I was talking about before, the fact of perceiving yourself as part of the world, is a faith, because it implies a belief, a deep and spontaneous acceptance.

—Michelangelo Frammartino

Le Quattro Volte is indeed a divinatory work. Throughout its understated humility, simplicity and elegance, it perfectly embodies a sacramental reverence to the pathos and humour of the rhythms of daily living and what is means to fully accept one’s part within the universe’s overarching scheme. Moreover, in the manner of similar “slow cinema” masterworks, such as Philip Gröning’s Into Great Silence and Edward A. Burger’s Amongst White Clouds, Michelangelo Frammartino has managed to achieve the almost impossible task of depicting the mysterious, transcendental quality of the very soul of existence itself thereby elevating the film to the realm of the sublime.

Post Notes

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Abbas Kiarostami: Certified Copy

- Spiros Stathoulopoulos: Meteora

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Paolo Sorrentino: The Great Beauty

- Edward A. Burger: Amongst White Clouds

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora

- Kim Ki-duk: Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

- Carlos Reygadas: Japón

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth

- Abbas Kiarostami: 24 Frames

- Kaneto Shindo: The Naked Island