Windows and mirrors

“I think of spirituality as a personal and subjective aspect of each and every individual.

Travelling around the world, I have experienced different religions,

philosophies and belief systems

and have come to the conclusion that nobody has all the answers.

Rather, we wander around in a Cloud of Unknowing, asking questions.”

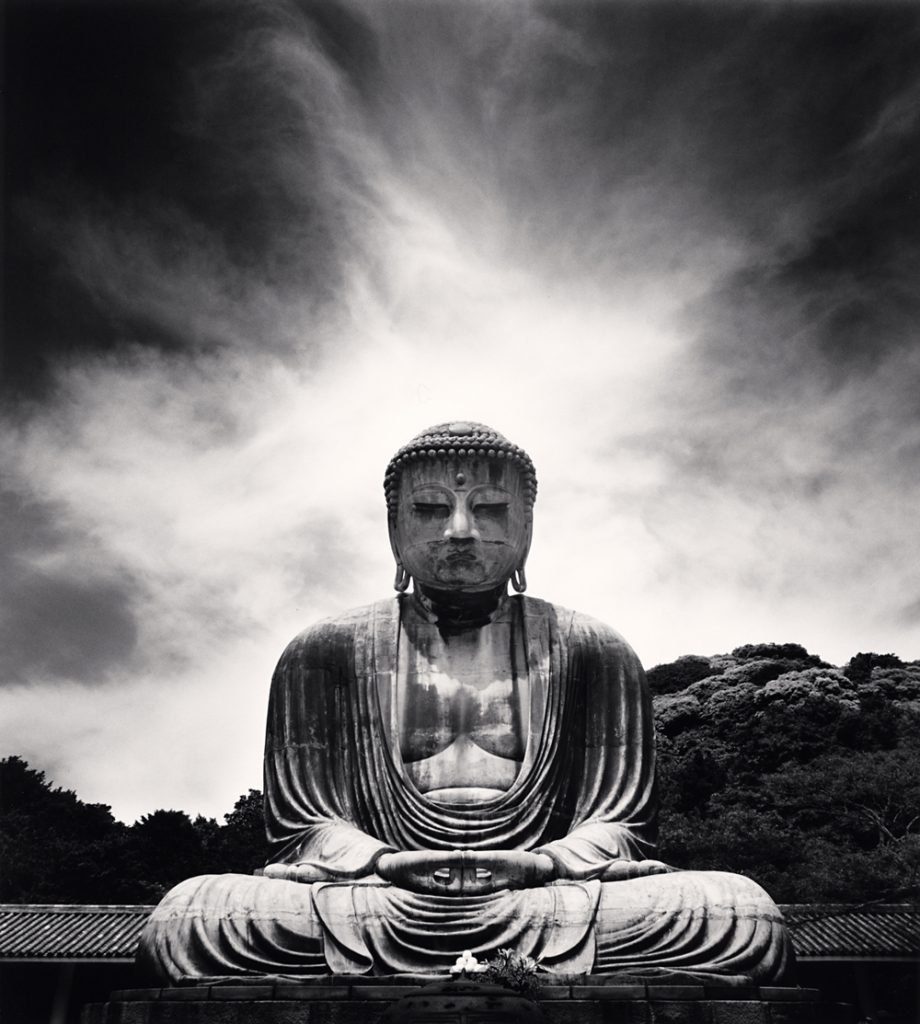

MICHAEL KENNA’s mysterious photographs, often made at dawn or in the dark hours of night, concentrate primarily on the interaction between the natural landscape and human-made structures. Kenna is both a diurnal and nocturnal photographer, fascinated by light when it is most pliant. With long time exposures, which might last throughout the night, his photographs often record details that the human eye is not able to perceive.

Kenna is particularly well-known for the intimate scale of his photography and his meticulous personal printing style. He works in the traditional, non-digital, silver photographic medium. His exquisitely hand-crafted black and white prints, which he makes in his own darkroom, reflect a sense of refinement, respect for history and thorough originality.

Born in 1953, during Kenna’s fifty-year career, his photographic prints have been shown in almost five hundred one-person exhibitions and over four hundred group exhibitions in galleries and museums throughout the world. They are also included in well over a hundred permanent institutional collections. Ninety monographs and exhibition catalogs have so far been published on Kenna’s work.

In 2022, he was made an Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters, Ministry of Culture, Paris, France. He currently lives in Seattle, WA, USA.

The following interview is reproduced with kind permission from a special black-and-white issue of SOULFUL PHOTOGRAPHY No. 8 (March/April 2025) by the magazine’s founder and editor, Kedar Misani.

When did you realize your passion for photography?

I was born and brought up in what might be described as a poor, working class family in Widnes, an industrial town near Liverpool. I was the youngest in our family, with one sister and four brothers. There wasn’t that much space in our home. So I spent a lot of time wandering, often on my own, around the town, in Victoria Park across the road, the local pond (Sacey’s Pit), the railway station (Widnes North), the Runcorn-Widnes bridge across the River Mersey, Cronton Colliery, the rubbish tip, various factories, the nearby St Bede’s church, the ‘Chemics’ rugby league ground (Naughton Park), and many other places. It seemed completely safe to be out on your own in those days.

Were there any photographers that influenced/inspired you?

My first and strongest photographic influences and inspirations were the European masters—Eugene Atget, Bill Brandt, Mario Giacomelli and Josef Sudek. I suppose they are all romantics at heart, concerned with photographing a feeling as much as documenting external reality. Eugene Atget inspired me to photograph Le Notre Gardens in and around Paris. His dedication to photographing Paris all his life taught me that nothing is ever the same. The same subject matter can be photographed in different ways and in different conditions.

Bill Brandt took me back to the industrial towns in the North West of England. He showed me that beauty is in every subject matter and very much in the mind of the beholder. His sense of drama, even melodrama, his use of atmosphere, his willingness to completely change reality into an abstract and graphic print, all helped my own vision. He also taught me the value of empty space in an image.

Mario Giacomelli’s sense of powerful two-dimensional black and white abstraction and design profoundly affected me. Here was somebody who would use a thick marking pen to fill in black lines on the photographic print. I loved his liberation from the traditional fine art photographic print.

Josef Sudek taught me that light can emanate from within the subject matter rather than only illuminating the exterior. His images reminded me of infrared studies. His commitment to photograph only Prague was also instructive. With all these photographers, I actively searched out places where they had photographed, their camera angles and techniques. There were many other photographers who would influence me as the years progressed.

Were you always in black and white and if yes, why?

As a student, I photographed in colour and my final visual thesis was a study of body motion, influenced by the work of Harold Edgerton. My first representation in galleries in the USA was with that work. In my commercial work, I have often photographed in colour. However, I personally find black and white photographs to be more expressive, malleable and mysterious than those made in colour. Perhaps it is because we experience everyday life in colour. Therefore, a rendering in black and white is immediately more special and recognizable as a subjective interpretation rather than a copy of what has been seen. Colour tends to be specific and descriptive, and I prefer suggestion over description. For me, the subtlety of black and white inspires the imagination of the individual viewer to complete the picture in their mind’s eye. It doesn’t attempt to compete with the outside world. I believe it is calmer and more gentle than colour and persists longer in our visual memory.

Which country photographically fascinates you the most?

I have photographed in over forty countries so far and I have no intention to imply or suggest that any one country is more fascinating than another. Having said that, it is is obvious that I have photographed in some countries far more than in others and as one of my most recent books was titled Japan—A Love Story, I can talk about this project.

Physically, Japan has similarities to my home country of England: relatively small, inhabited for centuries, surrounded by water, with every patch of land and segment of coast full of rich histories and stories. There is something wonderfully mysterious and alluring in the Japanese landscape. It is visually manifested in the omnipresent interactions between earth, sky, and water, and in the constantly changing seasons. It can be felt in the engaging intimacy of scale in its terrain and in the deep sense of history contained in its earth. In Japan, one sees and feels a conscious respect, reverence and honour shown towards the land. It is often symbolized by the ubiquitous vermillion torii gates, which remind us that deities and the universe reside in the land, trees, rocks, and water, as well as in shrines and temples. It is a belief dear to my heart.

Then, there is the Northern island of Hokkaido, an intriguing and attractive place, particularly in the frozen winter months. I find it to be gently seductive, dangerously wild, and hopelessly romantic. It is a place where the reduction of sensory distractions, absence of colour, and eerie silences accentuate an awareness of the elements and encourage a more concentrated and pure focus on the land. Minimalism and sparseness are perhaps the inevitable results, which align perfectly with my own interests and influences.

What about the spiritual aspects of photography?

I think of spirituality as a personal and subjective aspect of each and every individual. Travelling around the world, I have experienced different religions, philosophies and belief systems and have come to the conclusion that nobody has all the answers. Rather, we wander around in a Cloud of Unknowing, asking questions.

I recall a John Szarkowki curated exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York titled Mirrors and Windows. His premise was that we photograph both what we see outside of ourselves, as if through a window, and simultaneously, we also have the possibility to reflect our own character and belief systems as if we were looking into a mirror. A central component of my approach to photography is that it is simply a conversation between photographer and subject matter, with viewers invited to participate later on. I hope that my works can be considered catalysts for other imaginations and experiences. They do not give answers but I hope at least they ask some questions.

You still work with film and silver prints. Never tempted to go digital?

I am still 100% analogue in terms of photographing, printing, retouching, mounting and matting, and exhibiting. I use film cameras and insist on making all prints myself in my own traditional wet darkroom. I don’t believe that analogue is any better than digital, or the reverse, for that matter. But I do believe they are different, and it is my personal preference and choice to remain with the traditional silver process.

How do you present your prints? Any limited editions or portfolios?

A few years ago, I had an exhibition of my tree studies at Chateau de Chaumont in Chaumont-sur-Loire, France. During the press conference, I referred to the 100 or so prints on the wall as my family. Prints from the seventies and eighties were comfortably hanging next to prints made the previous month. They were all formatted similarly. For the most part, my prints are sepia-toned silver gelatin, made by me in a traditional darkroom from original negatives. I limit the amount and size of prints I make from any one negative. I may not actually make all the prints in an edition as it ultimately depends on how many sell but the edition size is the maximum number of prints I would make from a negative.

My standard edition size before 2017 was 45 and 4 artist proofs. Since then, the edition size has been 25 and 3 artist proofs for all new work. Print size for both the editions of 45 and 25 is about 7.5 inches square, and prints are mounted and matted on 16 x 20-inch vertical white museum board (4-ply backing, 2-ply front). Prints are retouched by hand, signed, dated and numbered on the front, below the print. They are also stamped, titled, negative dated, print dated, and signed on the back of the mounting board. Occasional extra exhibition prints are made from sold-out editions for museum shows, but these are not sold.

What is your next project?

Like all of us, I get older every day. The certainty that I am closer to the end of my journey than to the beginning makes me appreciate more than ever that life is finite. My needs are fairly straightforward: long walks, time with good friends and close family, some solitude now and then. Photography continues to be a passion for me, and I generally work on multiple projects over long periods of time. With an archive of over 175,000 negatives, I probably already have more than enough images to keep me busy printing for the rest of my life, even if I retired my cameras right now, which I have no intention of doing. I regard the subject matter that I connect with to be collaborative partners and friends, and I must admit that at this time of life, deepening existing relationships is proving to be an ever higher priority than seeking out new places and new friends. My future intentions are simply to live life and enjoy every second to the best of my ability and potential.

For further information on his work, visit Michael Kenna’s website.

Single issues and subscriptions of SOULFUL PHOTOGRAPHY are available from Kedar Misani’s website.

Post Notes

- Feature image: © Michael Kenna, Three Bodhisattvas, Osorezan, Honshu, Japan, 2005

- Michael Kenna’s website

- SOULFUL PHOTOGRAPHY website

- Huibo Hou: Iceland

- Sally Mason: Silence in the Landscape

- Marian Kraus: Colours & Forms

- Markéta Luskačová & Gabriel Rosenstock: Pilgrim Soul

- John Devitt: Cloud Illusions

- Ditmar Bollaert: Arunachala Pradakshina

- Tobias Wilkinson: German Forest Primer

- Danila Tkachenko: Escape

- Ron Rosenstock: The Invisible Light

- Ansel Adams: The Search for Beauty

- Roy Whenary: Open Awareness

- Jerry Katz: Let the Scene See You

- Andy Richter: Serpent in the Wilderness

- Laura Emerson: Deep Sea Contemplation

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme