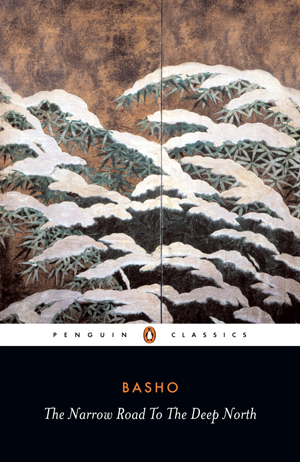

2. Clear Morning.

Photograph: Public Domain

Dreams wander on

Days and months are the travellers of eternity. So are the years that pass by. Those who steer a boat across the sea, or drive a horse over the earth till they succumb to the weight of years, spend every minute of their lives travelling. There are a great number of the ancients, too, who died on the road. I myself have been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind—filled with a strong desire to wander …

It was early on the morning of March the twenty-seventh that I took to the road. There was darkness lingering in the sky and the moon was still visible, though gradually thinning away. The faint shadow of Mount Fuji and the cherry blossoms of Ueno and Yanaka were bidding me a last farewell. My friends had got together the night before and they all came with me on the boat to keep me company for the first few miles. When we got off the boat at Senju, however, the thought of three thousand miles before me suddenly filled my heart and neither the houses of the town nor the faces of my friends could be seen by my tearful eyes except as a vision.

AND THUS THE opening lines of Bashō’s classic tale, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, entice us to accompany the Japanese haiku poet and diarist (1644–28th November 1694) on a tantalizing journey, at once a perilous expedition through seventeenth-century Japan and an individual quest for spiritual enlightenment. A devoted student of Zen Buddhism, Bashō describes with exquisite simplicity images of the natural world as he sets off in this elegant travelogue into the wilderness: the brightness of a full moon; the beauty of a waterfall; the baptism of falling rain.

Indeed, the Christian mystic, Thomas Merton—who himself produced metaphysical books of the highest order—was so captivated by Bashō’s work that he immediately composed a glowing review in his journal: “I went out this afternoon, read some stuff on meditation … Then came back and began a new Penguin containing Bashō’s travel notes. Completely shattered by them. One of the most beautiful books I have ever read in my life. It gives me a whole new (old) view of my own life. The whole thing is pitched right on my tone. Deeply moving in every kind of way. Seldom have I found a book to which I responded so totally.”

6. The Circular Pine Trees of Aoyama.

Photograph: Public Domain

“It is with awe

That I beheld

Fresh leaves, green leaves,

Bright in the sun.”

Haiku, or hokku as it was known in Bashō’s day, is one-breath poetry, traditionally seventeen syllables (5-7-5), usually presented in translation in three or four lines. With its subtle yet succinct literary structure, the haiku is particularly suited for emotive expression and even spiritual revelation, executed through the delicate use of metaphors depicting the passing seasons of nature as well as domestic scenes from everyday life.

As Bashō wrote himself: “What is important is to keep our mind high in the world of true understanding and returning to the world of our daily experience to seek therein the truth of beauty. No matter what we may be doing at a given moment, we must not forget that it has a bearing upon our everlasting self, which is poetry.”

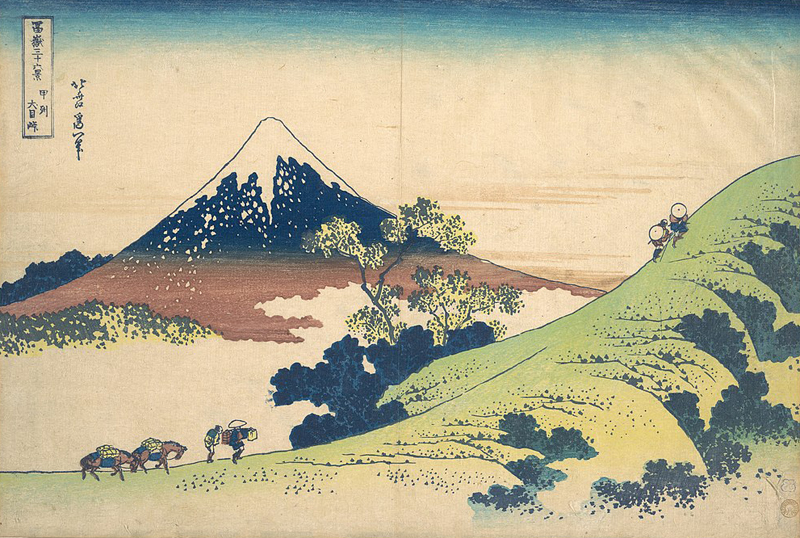

8. The Inume Pass in Kai Province.

Photograph: Public Domain

“Turn the head of your horse

Sideways across the field,

To let me hear

The cry of the cuckoo.”

Matsuo Kinsaku was born in Iga-ueno near Kyoto in 1644, adopting the nom de plume, Bashō, after one of his disciples presented him with a banana tree (or bashō tree), to which he formed a deep attachment, mentioning it several times in his poetry as well as bestowing the name upon his isolated hut, the first of three hermitages he would own over the course of his relatively short life.

It was also during these solitary years that Bashō embarked upon an intense meditative practice, under the guidance of a local Zen Buddhist priest. A house fire, followed shortly after by the death of his mother, further precipitated a deepening need to renounce the trappings of the material world and thus he set off to discover his inner, poetic self: “Go to the pine if you want to learn about the pine or to the bamboo if you want to learn about the bamboo. And in doing so, you must leave your subjective preoccupation with yourself. Otherwise, you impose yourself on the object and do not learn. Your poetry issues of its own accord when you and the object have become one—when you have plunged deep enough into the object to see something like a hidden glimmering there. However well phrased your poetry may be, if your feeling is not natural—if the object and yourself are separate—then your poetry is not true poetry but merely your subjective counterfeit.”

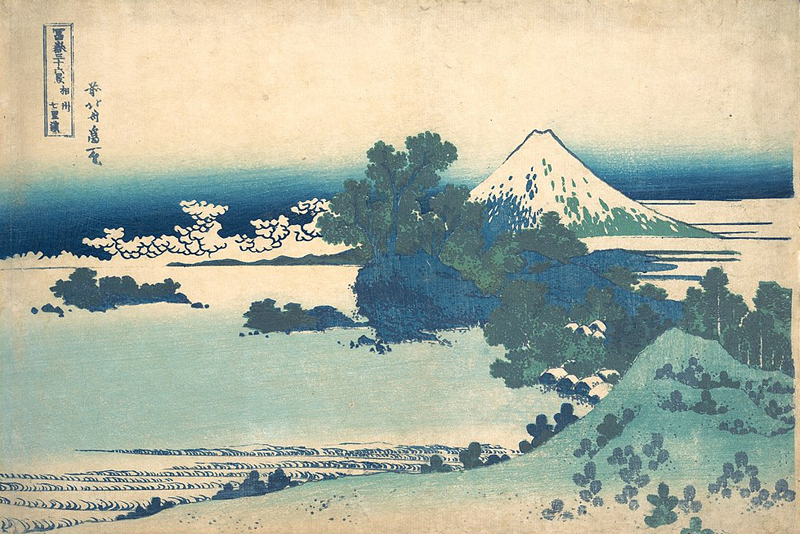

18. Tago Bay Near Ejiri on the Tokaido.

Photograph: Public Domain

“Mingled with tiny shells

I saw scattered petals

Of bush-clovers

Rolling with the waves.”

Bashō was a compulsive traveller, often walking for many months with scant provisions and money, relying purely on the hospitality of Buddhist priests and fellow poets. And yet his peripatetic wanderings enabled him to devote himself entirely to his artistic talents whilst simultaneously embracing the spiritual path.

Indeed, Bashō’s ascetic lifestyle enabled him to develop a particular form of prosimetric writing—the haibun—that combines a prose poem with a haiku, whereby each form reflects the essence of the other, elevating his versification to ever greater heights.

Photograph: Public Domain

There was a temple called Ryushakuji in the province of Yamagata. Founded by the great priest Jikaku, this temple was known for the absolute tranquillity of its holy compound. Since everybody advised me to see it, I changed my course at Obanazawa and went there, though it meant walking an extra seven miles or so. When I reached it, the late afternoon sun was still lingering over the scene. After arranging to stay with the priests at the foot of the mountain, I climbed to the temple situated near the summit. The whole mountain was made of massive rocks thrown together and covered with age-old pines and oaks. The stony ground itself bore the colour of eternity, paved with velvety moss. The doors of the shrines built on the rocks were firmly barred and there was no sound to be heard. As I moved on all fours from rock to rock, bowing reverently at each shrine, I felt the purifying power of this holy environment pervading my whole being.

In the utter silence

Of a temple,

A cicada’s voice alone

Penetrates the rocks.I wanted to sail down the River Mogami but while I was waiting for fair weather at Oishida, I was told that the old seed of linked verse once strewn here by the scattering wind had taken root, still bearing its own flowers each year and thus softening the minds of rough villagers like the clear note of a reed pipe, but that these rural poets were now merely struggling to find their way in a forest of error, unable to distinguish between the new and the old style, for there was no one to guide them. At their request, therefore, I sat with them to compose a book of linked verse and left it behind me as a gift. It was indeed a great pleasure for me to be of such help during my wandering journey.

27. The Tama River, Musashi Province.

Photograph: Public Domain

“The first poetic venture

I came across—

The rice planting songs

Of the far north.”

Alongside his haiku poetry anthologies, Bashō wrote a number of haibun about his travels: The Records of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton; A Visit to Kashima Shrine; The Records of a Travel-Worn Satchel; and, his final masterwork, The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no Hosomichi).

It was in the spring of 1689 that Bashō left Edo, embarking on his third major journey and last travel sketch, spending more than two and a half years on the road. Rather than take the familiar routes around central Japan that he had traversed in the past, he explored the unfamiliar territory of the northern provinces, as they represented for Bashō a voyage into the eternal and timeless, all the while his being only too mindful of the pathos of things—mono no aware—and the impermanence of all life.

30. Shichirigahama in Sagami Province.

Photograph: Public Domain

“Dwarfed pine is indeed

A gentle name, and gently

The wind brushes through

Bush-clovers and pampas.”

Despite the fact that the principles of Japanese aesthetics were only formalized in the nineteenth century, Bashō’s prose and poetry are pervaded by many of their foundational ideals, including the notion of mono no aware. Other concepts also permeate his writings; for example, yugen, a subtle experience of mystery; wabi, a satisfaction in simple everyday objects; sabi, a love of transcience and solitude.

Indeed, it is this sense of dusting off the world and voyaging into the unknown that enthrals us so much, particularly in a postmodernist time period, where irony and irreverence reign supreme. Moonlight, birdsong, soughing leaves … Bashō’s compositions leave us utterly spellbound.

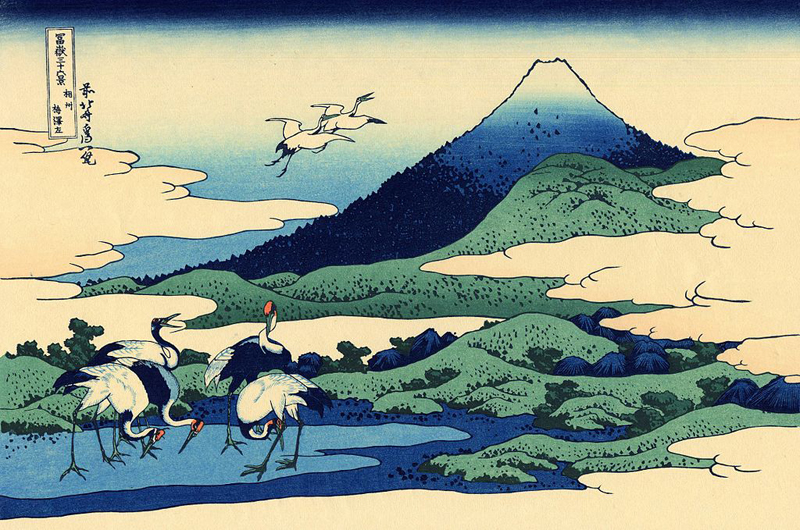

31. Umezawa Manor in Sagami Province.

Photograph: Public Domain

“Cranes hop around

On the watery beach of Shiogoshi

Dabbling their long legs

In the cool tide of the sea.”

The Narrow Road to the Deep North joins a body of literature specifically aligned with wandering through the wilds of nature, at the crossroads between the real and the unreal. Henry David Thoreau, Jack Kerouac, Ryōkan, Herman Hesse, Rainer Maria Rilke, to name but a few, all spent their time in the search of the suchness of the universe, leaving behind the literary spoors of their travels, evoking us to do the same.

As Bashō himself reminds us, “… you must leave your subjective preoccupation with yourself.” No wiser words could be more liberating and pertinent as we embrace the road less travelled on own our journey through this blessed life.

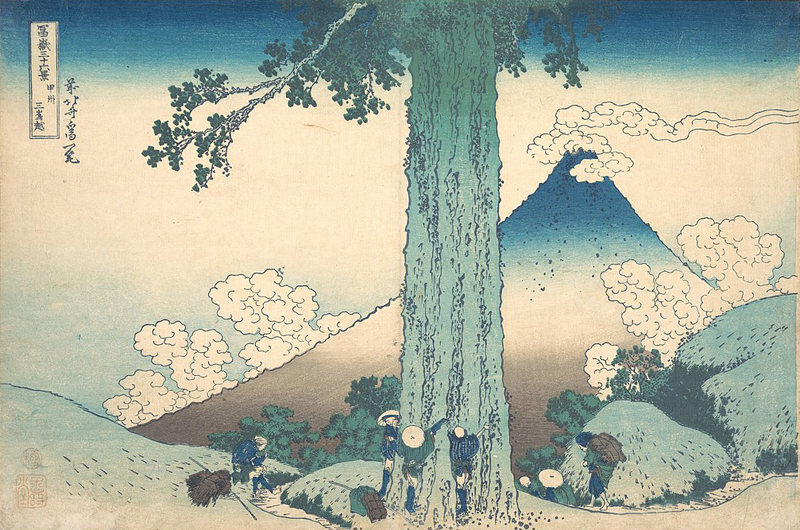

33. Mishima Pass in Kai Province.

Photograph: Public Domain

In this little book of travel is included everything under the sky—not only that which is hoary and dry but also that which is young and colourful, not only that which is strong and imposing but also that which is feeble and ephemeral. As we turn every corner of the Narrow Road to the Deep North, we sometimes stand up unawares to applaud and we sometimes fall flat to resist the agonizing pains we feel in the depths of our hearts. There are also times when we feel like taking to the road ourselves, seizing the raincoat lying nearby, or times when we feel like sitting down till our legs take root, enjoying the scene we picture before our eyes. Such is the beauty of this little book that it can be compared to the pearls which are said to be made by the weeping mermaids in the far off sea. What a travel it is indeed that is recorded in this book, and what a man he is who experienced it. The only thing to be regretted is that the author of this book, great man as he is, has in recent years grown old and infirm with hoary frost upon his eyebrows.

—Early summer of the seventh year of Genroku (1694), Soryu [scholar and priest from Edo, who made a clean copy of The Narrow Road to the Deep North at Bashō’s request]

Post Notes

- Matsuo Bashō: Deep Silence

- Matsuo Bashō et al.: Four Huts

- Emergence Magazine: On the Road With Thomas Merton

- Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- Kaneto Shindo: The Naked Island

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Waldeinsamkeit

- Alan Watts: Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- Henry David Thoreau: Walking

- Liam Ó Muirthile: Camino de Santiago, Dánta, Poems, Poemas