Asian writings on the simple life

“A new thatched hall, five spans by three;

stone steps, cassia pillars, fence of plaited bamboo.

The south eaves catch the sun, warm on winter days;

a door to the north lets in breezes, cool in summer moonlight.”

—Po Chü-i

LITERATURE IS RIFE with odes to the way of the solitary householder, from Henry David Thoreau’s love letter in praise of Walden Woods to Jack Kerouac’s reflections on being a lone fire lookout on Desolation Peak. Whatever the location or circumstance, a modest hut or homestead is seen as the quintessential means to finding peace, inner contentment and even realization of the Self.

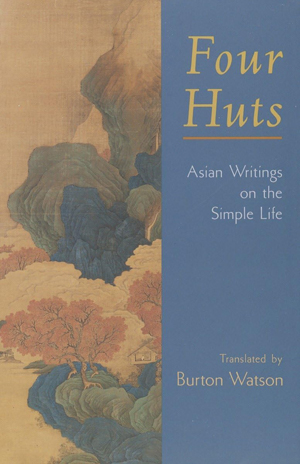

In this exquisite slim volume of short essays, beautifully translated by the accomplished American sinologist Burton Watson and illustrated by artist Stephen Addiss, Four Huts: Asian Writings on the Simple Life considers the house as a metaphor both for the householder himself as well as the particular kind of life lived within its confines. Drawing on Chinese and Japanese culture, each monograph subtly conveys the writer’s unique philosophical views and aesthetic sensibilities, be it in the midst of a bustling city or far away from the madding crowds.

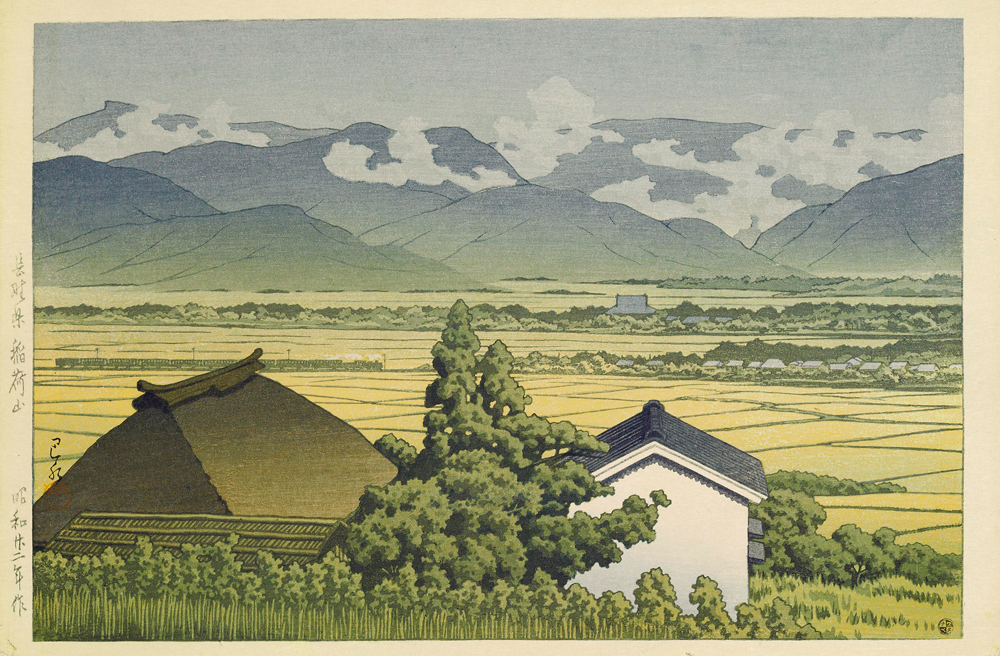

First in the collection is Po Chü-i (772–846), a popular and prolific T’ang poet, who worked as a government official. Accused of overstepping his authority, he was demoted to a lowly district post as a marshal in a remote rural area south of the Yangtze River, where he made frequent trips to nearby Mount Lu. Inspired by the scenery, with its many Buddhist and Taoist temples, Po determined to build a mountain retreat to visit when undetained by civic duties. Sadly, only two years after its completion, he was transferred to a different post in another Chinese province, far away from his beloved thatched hall.

K’uang Lu, so strange, so superb it tops all the mountains in the empire! The northern peak is called Incense Burner Peak, and the temple there is called the Temple of Bequeathed Love. Between the temple and the peak is an area of superlative scenery, the finest in all Mount Lu. In autumn of the eleventh year of the Yüan-ho era [816] I, Po Lo-t’ien of T’ai-yüan, saw it and fell in love with it. Like a traveller on a distant journey who passes by his old home, I felt so drawn to it I couldn’t tear myself away. So on a site facing the peak and flanking the temple I set about building a grass-thatched hall.

By spring of the following year the thatched hall was finished. Three spans, a pair of pillars, two rooms, four windows—the dimensions and expenditures were all designed to fit my taste and means. I put a door on the north side to let in cool breezes so as to fend off oppressive heat, made the southern rafters hight to admit sunlight in case there should be times of severe cold. The beams were trimmed but left unpainted, the walls plastered but not given a final coat of white. I’ve used slabs of stone for paving and stairs, sheets of paper to cover the windows, and the bamboo blinds and hemp curtains are of a similar makeshift nature. Inside the hall are four wooden couches, two plain screens, one lacquered ch’in [zitherlike stringed instrument], and some Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist books, two or three of each kind.

—Po Chü-i, Record of the Thatched Hall on Mount Lu

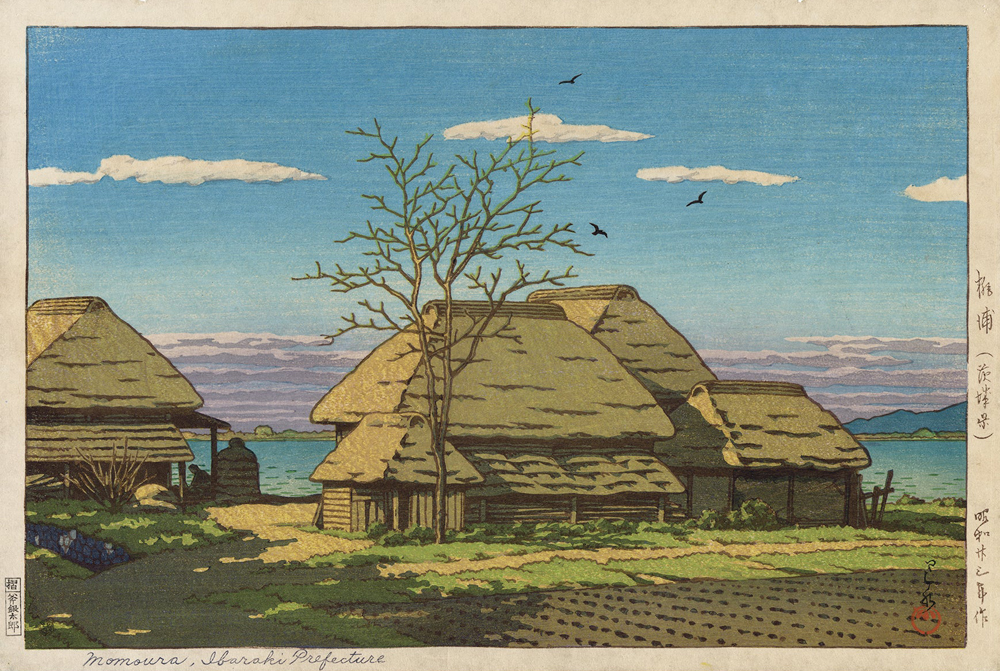

The son of a Kyoto family specializing in divination and geomancy, Yoshishige no Yasutane (c. 933–997) worked in a succession of government posts after studying Chinese history and literature. When his own son had reached the age of maturity, he retired from public life and became a Buddhist monk. Unlike Po Chü-i’s record of an idyllic mountain abode, Yasutane’s describes a magnificent pavilion right in the heart of the Japanese capital.

So, after five decades in the world, I’ve at last managed to acquire a little house, like a snail at peace in his shell, like a louse in the seam of a garment. The quail nests in the small branches and does not yearn for the great forest of Teng; the frog lives in his crooked well and knows nothing of the vastness of the sweeping seas. Though as master of the house I hold office at the foot of the pillar, in my heart it’s as though I dwelt among the mountains. Position and title I leave up to fate, for the workings of Heaven govern all things alike. Heaven and earth will decide if I live a long life or a short one—like Confucius, I’ve been praying for a long time now. I do not envy the man who soars like a phoenix on the wind, nor the man who hides like a leopard in the mists. I have no wish to bend my knee and crook my back in efforts to win favour with great lords and high officials but neither do I wish to shun the words and faces of others and bury myself away in some remote mountain or dark alley.

During such time as I am at court, I apply myself to the business of the sovereign; once home, my thoughts turn always to the service of the Buddha. When I go abroad, I don my grass-green official robe, and though my post is a minor one, I enjoy a certain measure of honour. At home I wear white hemp garments, warmer than spring, purer than the snow. After washing my hands and rinsing my mouth, I ascend the eastern hall, call on the Buddha Amida, and recite the Lotus Sutra. When my supper is done, I enter the eastern library, open my books, and find myself in the company of worthy men of the past, those such as Emperor Wen of the Han, a ruler of another era, who lived frugal ways and gave rest to his people; Po Lo-t’ien of the T’ang, a teacher of another time, who excelled in poetry and served the Buddhist Law; or the Seven Sages of the Chin dynasty, friends of another age, who lived at court but longed for the life of retirement. So I meet with a worthy ruler, I meet with a worthy teacher and I meet with worthy friends, three meetings in one day, three delights to last a lifetime. As for the people and affairs of the contemporary world, they hold no attraction for me. If in becoming a teacher one thinks only of wealth and honour and is not concerned about the importance of literature, it would be better if we had no teachers. If in being a friend one thinks only of power and profit and cares nothing about the frank exchange of opinions, it would be better if we had no friends. So I close my gate, shut my door and hum poems and sing songs by myself. When I feel the desire for something more, my boys and I climb into the little boat, thump the gunwale, and rattle the oars. If I have some free time left over, I call the groom and we go out to the vegetable garden to pour on water and spread manure. I love my house—other things I know nothing about.

—Yoshishige no Yasutane, Record of the Pond Pavilion

Hōjōki or Record of the Ten-Foot-Square Hut by Kamo no Chōmei (1153–1216) is a seminal classic of Japanese literature. Drawing heavily on Yoshishige no Yasutane’s work in classical Chinese poetry, Chōmei composed his own offering in elegant Japanese prose. Forbidden to follow his father’s footsteps into the Shinto priesthood, he devoted his energies instead to poetry and music, being an accomplished player of the lute. At fifty, having no wife or children, he renounced secular life and became a Buddhist monk. His literary narrative became an important critique of contemporary society as well as an account of many natural disasters—fires, famines and earthquakes—that plagued the time.

This threefold world of ours is a creation of the mind [desire, form and formlessness]. If the mind is not at ease, then the finest horses and elephants, the seven precious substances, all seem worthless, and palaces and pleasure towers hold no allure. But now I find myself loving this lonely dwelling, my one-room hut. I feel ashamed whenever circumstances oblige me to go to the capital and beg for alms. But once back in my mountain, I can only pity those who chase after worldly gain. If people doubt what I say, let them look at the fish and birds. The fish never tire of the water, yet if one is not a fish, one can hardly understand what is in the fish’s mind. Birds only long for the forest, but if one is not a bird, one cannot understand why. The same apples to these delights of the quiet life. Without living such a life, how can one comprehend them?

Now my term draws to a close, like a moon nearing the rim of the mountain as it sinks in the sky. Soon I will face the darkness of Sanzu River. What use now in grumbling? The teachings of the Buddha warn us against feelings of attachment. So now it must be wrong for me to love this thatched hut of mine and my fondness for quiet and solitude must be a block to my salvation. Why have I wasted precious time in the recital of these useless pleasures? In the stillness of dawn I go on pondering these truths and I put this question to myself: You say you’ve abandoned the world and come to live in the mountain forest so you can discipline your mind and practise the Way. But however much you imitate a saint’s appearance, your mind is still steeped in impurity. In your dwelling you presume to copy the ways of the lay believer Pure Name [Vimalakirti] but in religious attainment you can’t even equal Shuddhipanthaka [the least apt of Buddha’s disciples]! Is this because you let the poverty that is your lot in life distract you or have vain delusions unbalanced your mind? At that time my mind could give no answer. All I could do was call upon my tongue to utter two or three recitations of Amida Buddha’s name, ineffctual as they might be, before falling silent.

—Kamo no Chōmei, Record of the Ten-Foot-Square Hut

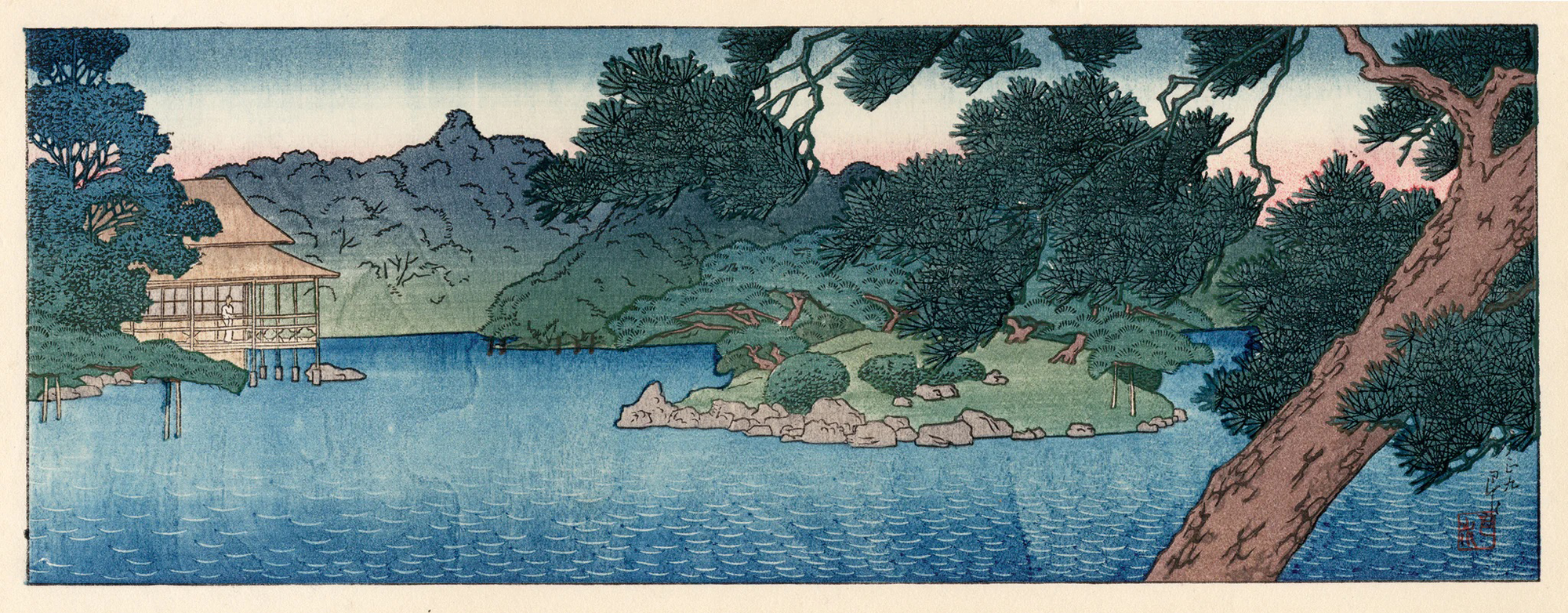

The final composition comes from the pen of the famous Japanese haikuist, Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694). The shortest and sunniest in outlook, his Record of the Hut of the Phantom Dwelling details his homestead on a hill on the southern shore of Lake Biwa east of Kyoto. Remaining unmarried all his life, he devoted his time to poetry and religious training under a Zen master. Unlike the sociophilosophical works of Yoshishige no Yasutane and Kamo no Chōmei, Bashō returns to the personal reflections of Po Chü-i, bringing the book full circle to a neat and conclusive end.

Sometimes, when I’m in an energetic mood, I draw clear water from the valley and cook myself a meal. I have only the drip, drip of the spring to relieve my loneliness but with my one little stove, things are anything but cluttered. The man who lived here before was truly lofty in mind and did not bother with any elaborate construction. Outside of the one room where the Buddha image is kept, there is only a little place designed to store bedding …

But when all has been said, I’m not really the kind who is so completely enamoured of solitude that he must hide every trace of himself away in the mountains and wilds. It’s just that, troubled by frequent illness and weary of dealing with people, I’ve come to dislike society. Again and again I think of the mistakes I’ve made in my clumsiness over the course of the years. There was a time when I envied those who had government offices or impressive domains, and on another occasion, I considered entering the precincts of the Buddha and the teaching rooms of the patriarchs. Instead, I’ve worn out my body in journeys that are as aimless as the winds and clouds, and expended my feelings on flowers and birds. But somehow I’ve been able to make a living this way, and so in the end, unskilled and talentless as I am, I give myself wholly to this one concern, poetry. Po Chü-i worked so hard at it that he almost ruined his five vital organs and Tu Fu [Chinese poet of the Tang Dynasty] grew lean and emaciated because of it. As far as intelligence or the quality of our writings go, I can never compare to such men. And yet we all in the end live, do we not, in a phantom dwelling? But enough of that—I’m off to bed.

Among these summer trees,

a pasania—

something to count on—Matsuo Bashō, Record of the Hut of the Phantom Dwelling

Post Notes

- Feature image: Kawase Hasui, Guest House in the Pines on Pond’s Edge, Public Domain

- Matsuo Bashō: The Narrow Road to the Deep North

- Matsuo Bashō: Deep Silence

- Emergence Magazine: On the Road With Thomas Merton

- Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- Kaneto Shindo: The Naked Island

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Waldeinsamkeit

- Alan Watts: Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- Henry David Thoreau: Walking

- Liam Ó Muirthile: Camino de Santiago, Dánta, Poems, Poemas

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme