How artists work

“Who can unravel the essence, the stamp of the artistic temperament!

Who can grasp the deep, instinctual fusion

of discipline and dissipation on which it rests!”

—Thomas Mann, Death in Venice

THE BUDDHISTS SAY that discipline sets you free. Indeed, anyone who has achieved a modicum of success, be it in the realm of spirituality, artistic endeavour, scientific exploration, or commercial business, understands that a high degree of regulated self-focus is the path to efficiency, prosperity and even transcendence from the confines of self.

As a child, I loathed the school timetable, forever monitoring my watch in double Physics, pining for liberation on the other side of four o’clock and the summer holidays beyond. Then I went to university and although the lecture schedule was much less restrictive, time was still carved out into the teaching terms of Michaelmas, Lent and Easter, meaning it was not until my mid-twenties that I first experienced the passing of a year without any overarching structure, other than the daily requirement of being at my desk between nine and five.

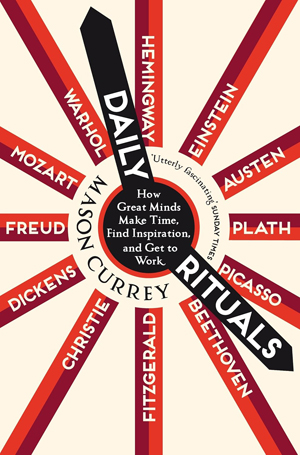

As I became more invested in spirituality and being creative, it was more and more apparent that having a daily routine was the only way to make any headway and I started experimenting with setting myself a curriculum of self-improvement, although its planning would often overtake the actual execution of the tasks involved. When I recently discovered the wonderful Daily Rituals, I was relieved and amused to read of the obsessional quotidian customs of other artists, deftly edited by American writer Mason Currey in this utterly compelling compendium of the routines and working habits of 161 male and female minds, from Beethoven to Donald Barthelme, Kafka to Georgia O’Keeffe.

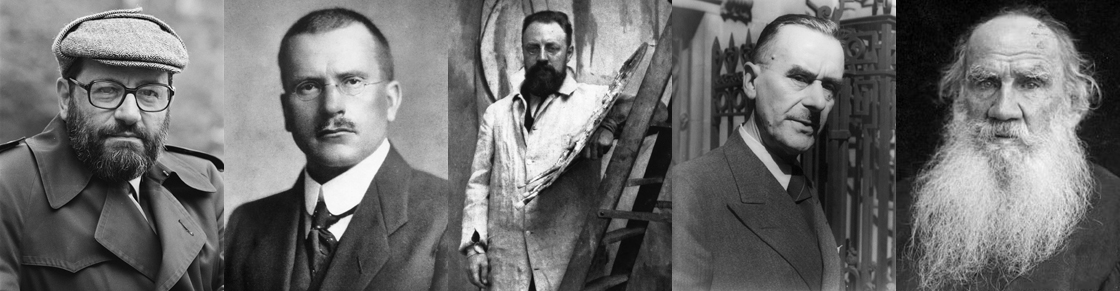

So herewith a selection of five extracts that particularly inspired me concerning the daily rituals of Umberto Eco, Carl Jung, Henri Matisse, Thomas Mann and Leo Tolstoy, prefaced with an apposite sentiment from Mason Currey in his introduction:

Writing it, I often thought of a line from a letter Kafka sent to his beloved Felice Bauer in 1912. Frustrated by his cramped living situation and his deadening day job, he complained, ‘Time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle manoeuvers.’ Poor Kafka! But then, who among us can expect to live a pleasant, straightforward life? For most of us, much of the time, it is a slog, and Kafka’s subtle manoeuvers are not so much a last resort as an ideal. Here’s to wriggling through.

[And for those wondering why I haven’t quoted any female artists, Currey’s magnificent follow-up collection, featuring only women, will be presented here soon!]

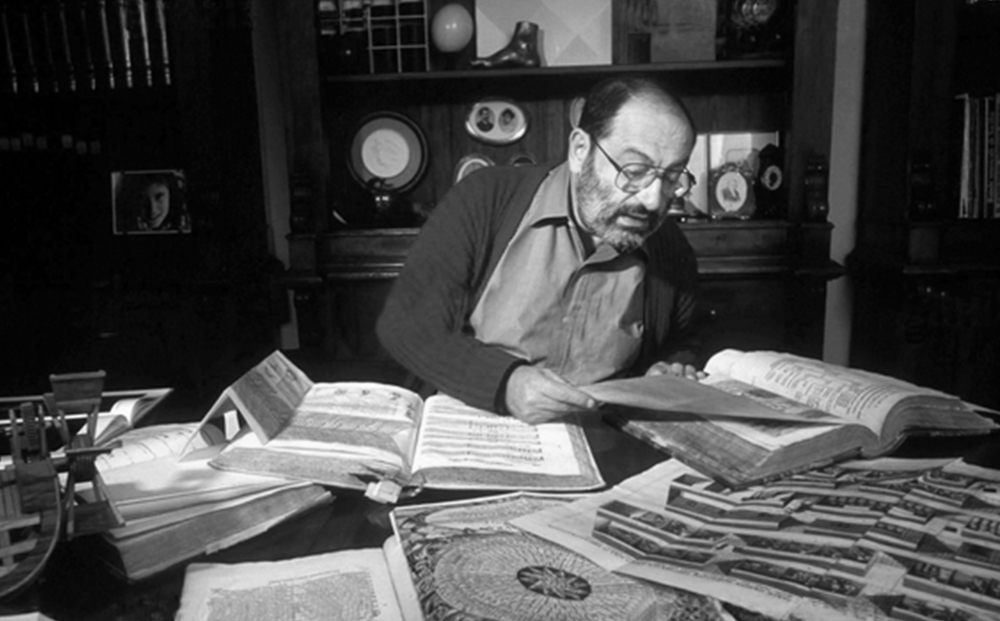

Umberto Eco (1932–2016)

The Italian philosopher and novelist—who is perhaps best known for his first novel, The Name of the Rose, published when he was 48 years old—claims that he follows no set writing routine. ‘There is no rule,’ he said in 2008. ‘For me, it would be impossible to have a schedule. It can happen that I start writing at seven o’clock in the morning and I finish at three o’clock at night, stopping only to eat a sandwich. Sometimes I don’t feel the need to write at all.’ When pressed by the interviewer, however, Eco admitted that his writing habits are not always so variable.

‘If I am in my countryside home, at the top of the hills of Montefeltro, then I have a certain routine. I turn on my computer, I look at my emails, I start reading something, and then I write until the afternoon. Later I go to the village, where I have a glass at the bar and read the newspaper. I come back home and I watch TV or a DVD in the evening until 11, and then I work a little more until one or two o’clock in the morning. There I have a certain routine because I am not interrupted. When I am in Milan or at the university, I am not master of my own time—there is always somebody else deciding what I should do.’

Even without blocks of free time, however, Eco says that he is able to be productive during the brief ‘interstices’ in the day. He told The Paris Review’s interviewer: ‘This morning you rang but then you had to wait for the elevator, and several seconds elapsed before you showed up at the door. During those seconds, waiting for you, I was thinking of this new piece I’m writing. I can work in the water closet, in the train. While swimming, I produce a lot of things, especially in the sea. Less so in the bathtub, but there too.’

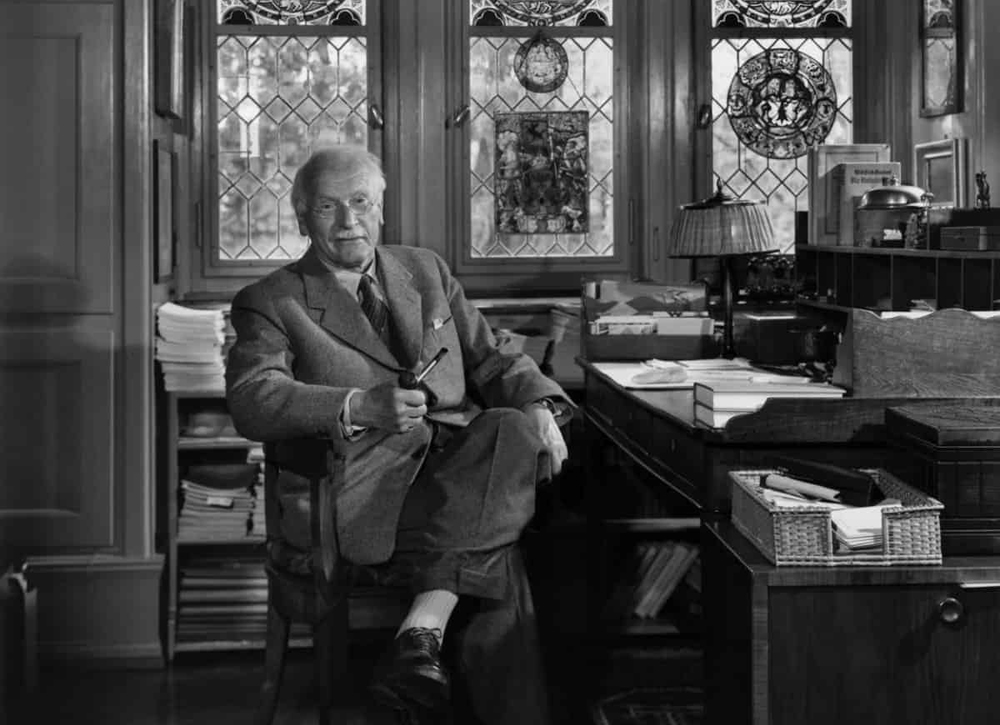

Carl Jung (1875–1961)

In 1922, Jung bought a parcel of land near the small village of Bollingen, Switzerland, and began construction on a simple two-storey stone house along the shore of the upper basin of Lake Zürich. Over the next dozen years, he modified and expanded the Bollingen Tower, as it became known, adding a pair of smaller auxiliary towers and a walled-in courtyard with a large outdoor fire pit. Even with these additions, it remained a primitive dwelling. No floorboards or carpets covered the uneven stone floor. There was no electricity and no telephone. Heat came from chopping wood, cooking was done on an oil stove, and the only artificial light came from oil lamps. Water had to be brought up from the lake and boiled (eventually, a hand pump was installed). ‘If a man of the 16th century were to move into the house, only the kerosene lamps and the matches would be new to him,’ Jung wrote; ‘otherwise, he would know his way about without difficulty.’

Throughout the 1930s, Jung used Bollingen Tower as a retreat from city life, where he led a workaholic’s existence, seeing patients for eight or nine hours a day and delivering frequent lectures and seminars. As a result, nearly all Jung‘s writing was done on holidays. (And although he had many patients who relied on him, Jung was not shy about taking time off; ‘I’ve realized that somebody who’s tired and needs to rest, and goes on working all the same is a fool,’ he said.)

At Bollingen, Jung rose at 7:00 am; said good morning to his saucepans, pots, and frying pans; and ‘spent a long time preparing breakfast, which usually consisted of coffee, salami, fruits, bread and butter,’ the biographer Ronald Hayman notes. He generally set aside two hours in the morning for concentrated writing. The rest of his day would be spent painting or meditating in his private study, going for long walks in the hills, receiving visitors, and replying to the never-ending stream of letters that arrived each day. At two or three o’clock, he took tea; in the evening, he enjoyed preparing a large meal, often preceded by an aperitif, which he called a ‘sundowner’. Bedtime was at 10 pm. ‘At Bollingen I am in the midst of my true life, I am most deeply myself,’ Jung wrote. ‘… I have done without electricity, and tend the fireplace and stove myself. Evenings, I light the old lamps. There is no running water, I pump the water from the well. I chop the wood and cook the food. These simple acts make man simple; and how difficult it is to be simple!’

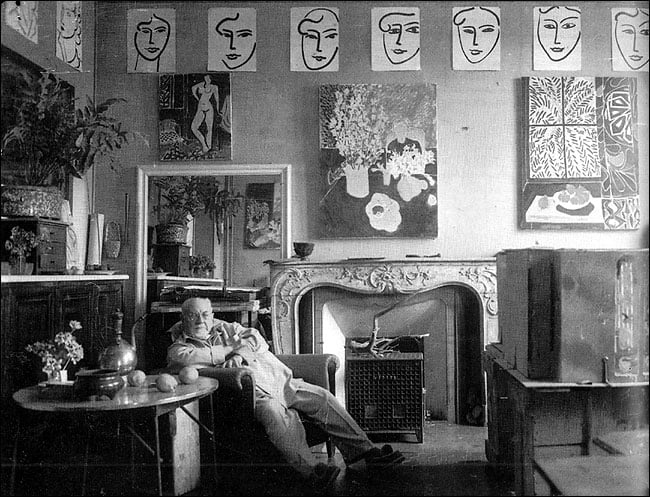

Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

‘Basically, I enjoy everything: I am never bored,’ Matisse told a visitor in 1941, during a tour of his studio in the south of France. After showing his guest his working space, his cages full of exotic birds, and his conservatory stocked with tropical plants, giant pumpkins, and Chinese statuettes, Matisse talked about his work habits.

‘Do you understand now why I am never bored? For over 50 years, I have not stopped working for an instant. From nine o’clock to noon, first sitting. I have lunch. Then I have a little nap and take up my brushes again at two in the afternoon until the evening. You won’t believe me. On Sundays, I have to tell all sorts of tales to the models. I promise them that it’s the last time I will ever beg them to come and pose on that day. Naturally, I pay them double. Finally, when I sense that they are not convinced, I promise them a day off during the week. “But Monsieur Matisse,” one of them answered me, “this has been going on for months and I have never had one afternoon off.” Poor things! They don’t understand. Nonetheless, I can’t sacrifice my Sundays for them merely because they have boyfriends.’

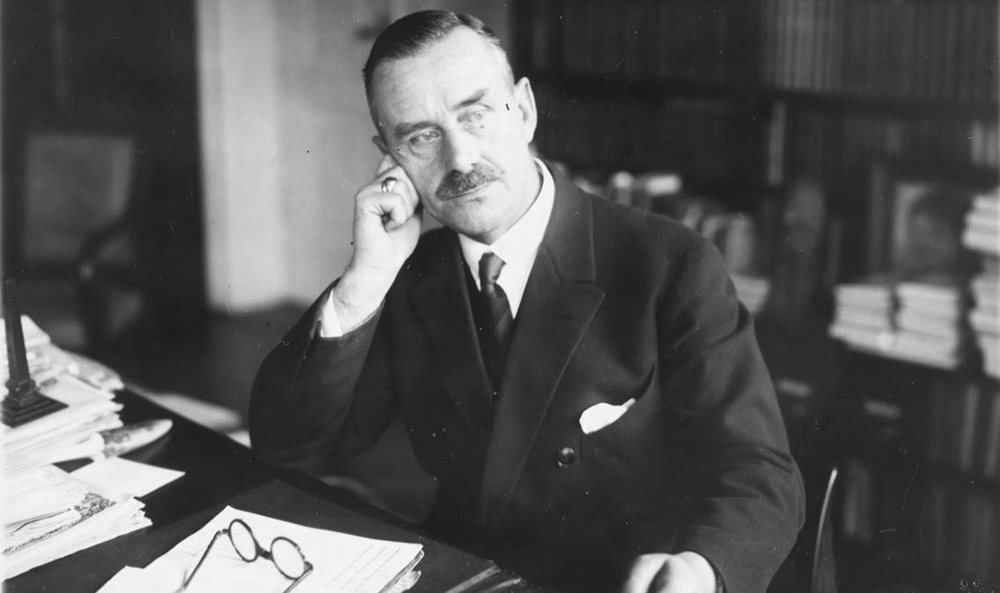

Thomas Mann (1875–1955)

Mann was always awake by 8:00 am. After getting out of bed, he drank a cup of coffee with his wife, took a bath, and dressed. Breakfast, again with his wife, was at 8:30. Then, at nine o’clock, Mann closed the door to his study, making himself unavailable for visitors, telephone calls, or family. The children were strictly forbidden to make any noise between 9:00 and noon, Mann’s prime writing hours. It was then that his mind was freshest, and Mann placed tremendous pressure on himself to get things down during that time. ‘Every passage becomes a “passage”,’ he wrote, ‘every adjective a decision.’ Anything that didn’t come by noon would have to wait until the next day, so he forced himself to ‘clench the teeth and make one slow step at a time.’

His morning grind over, Mann had lunch in his studio and enjoyed his first cigar—he smoked while writing but limited himself to 12 cigarettes and two cigars daily. He then sat on the sofa and read newspapers, periodicals, and books until 4:00, when he returned to bed for an hour-long nap. (Once again, the children were forbidden to make noise during the sacred hour.) At 5:00, Mann rejoined the family for tea. Then he wrote letters, reviews, or newspaper articles—work that could be interrupted by telephone calls or visitors—and took a walk before dinner at 7:30 or 8:00. Sometimes the family entertained guests at this time. If not, Mann and his wife would spend the evening reading or playing gramophone records before retiring to their separate rooms at midnight.

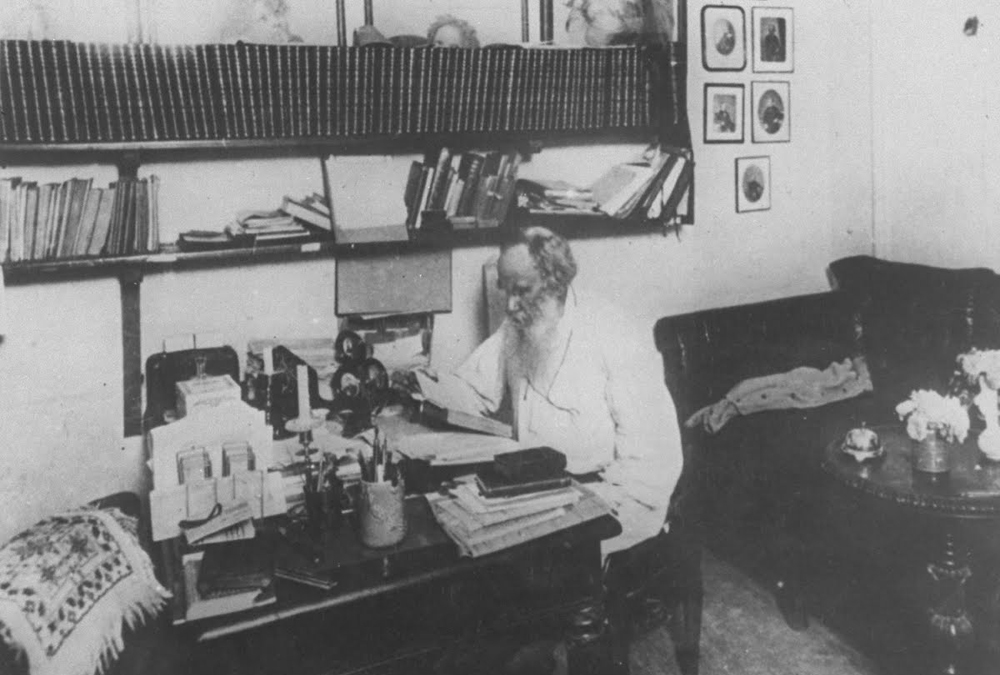

Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910)

‘I must write each day without fail, not so much for the success of the work, as in order not to get out of my routine.’ This is Tolstoy in one of the relatively few diary entries he made during the mid-1860s, when he was deep into the writing of War and Peace. Although he does not describe his routine in the diary, his oldest son, Sergei, later recorded the pattern of Tolstoy’s days at Yasnaya Polyana, the family estate in the Tula region of Russia:

‘From September to May, we children and our teachers got up between eight and nine o’clock and went to the hall to have breakfast. After nine, in his dressing-gown, still unwashed and undressed, with a tousled beard, Father came down from his bedroom to the room under the hall where he finished his toilet. If we met him on the way, he greeted us hastily and reluctantly. We used to say: “Papa is in a bad temper until he has washed.” Then he, too, came up to have his breakfast, for which he usually ate two boiled eggs in a glass. He did not eat anything after that until five in the afternoon. Later, at the end of 1880, he began to take luncheon at two or three. He was not talkative at breakfast and soon retired to his study with a glass of tea. We hardly saw him after that until dinner.’

According to Sergei, Tolstoy worked in isolation—no one was allowed to enter his study, and the doors to the adjoining rooms were locked to ensure that he would not be interrupted. (An account by Tolstoy’s daughter Tatyana disagrees on this point—she remembers that their mother was allowed in the study; she would sit on the divan sewing quietly while her husband wrote.) Before dinner, Tolstoy would go for a walk or a ride, often to supervise some work on the estate grounds. Afterward, he rejoined the family in a much more sociable mood. Sergei writes:

‘At five we had dinner, to which Father often came late. He would be stimulated by the day’s impressions and tell us about them. After dinner, he usually read or talked to guests if there were any; sometimes, he read aloud to us or saw to our lessons. About 10 pm all the inhabitants of [Yasnaya] foregathered again for tea. Before going to sleep, he read again, and at one time, he played the piano. And then retired to his bed about 1 am.’

Post Notes

- Feature image: Umberto Eco, Carl Jung, Henri Matisse, Thomas Mann, Leo Tolstoy, Public Domain & Fair Use

- Mason Currey’s website

- Leo Tolstoy: A Confession

- Michel de Montaigne: On Solitude

- Paula Marvelly: Sacra di San Michele

- Rousseau: Meditations of a Solitary Walker

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Rainer Maria Rilke: On Solitude

- Seneca: On Tranquillity of Mind

- Marcus Aurelius: Meditations

- David Whyte: Consolation

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Nature

- Alan Watts: Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme