Marie Menken, Glimpse of the Garden

The art of landscaping

“Marie’s films were her flower garden.

Whenever she was in a garden she opened her soul,

with all her secret wishes and dreams.”

—Jonas Mekas

WHY IS IT that when there is a global calamity, people inevitably turn to the Arts for solace and sustenance? As always when faced with an important conundrum, I seek out the artists themselves to furnish me with some kind of response. And who better than Russian auteur, Andrei Tarkovsky, someone I have oft-quoted on The Culturium, to make any kind of sense of the function of art: “[T]he goal of all art … is to explain to the artist himself and to those around him what man lives for, what is the meaning of his existence. To explain to people the reason for their appearance on this planet.”

But he goes further. In order to cultivate both an appreciation for art and the capacity to produce it, to find both the wellspring of our inner creative voice and the ability to harness its potential, the act of being alone is, first and foremost, a state to be nurtured. Indeed, when asked to give advice to young people on how to foster the artistic impulse, he advocated the need to enjoy solitude above all else:

I think I’d like to say only that they should learn to be alone and try to spend as much time as possible by themselves. I think one of the faults of young people today is that they try to come together around events that are noisy, almost aggressive at times. This desire to be together in order to not feel alone is an unfortunate symptom, in my opinion. Every person needs to learn from childhood how to spend time with oneself. That doesn’t mean he should be lonely but that he shouldn’t grow bored with himself because people who grow bored in their own company seem to me in danger, from a self-esteem point of view.

—Criterion Collection, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Message to Young People

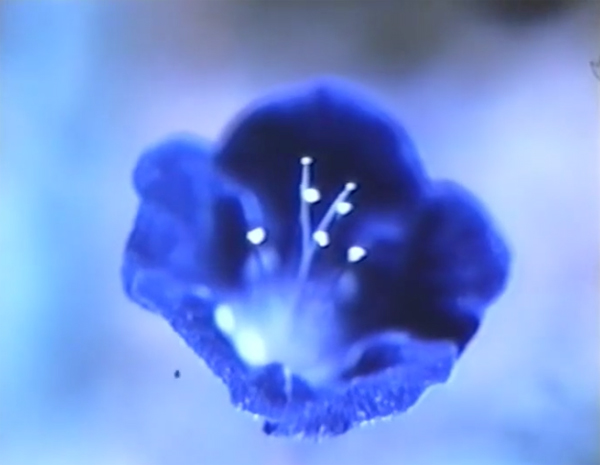

Photograph: © Marie Menken

A landscape, a face, a blotch of light—everything changes under their eyes to become something else, an essence of itself, at the service of their personal vision … The only signs, the only visible traces from which we can say … [that a … Menken film] passed nearby are the drops of happiness left on our faces, touches of joy. So actionless is their art.

—Jonas Mekas, Notes on Some New Movies and Happiness

Marie Menken (25th May 1909–29th December 1970) was no stranger to solitude and the art of cultivating an inner artistic landscape borne of her capacity to be alone. Considered to be one of the founding forefathers of American avant-garde cinema, Menken produced throughout her life a series of exquisitely shot moving image montages, elegantly revealing her intuitive understanding of the function of art, specifically filmmaking, in relation to the expression of the human soul.

Her dexterity with a hand-cranked Bolex was legendary and played a major influence for other experimental filmmakers of her generation—Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Jonas Mekas and Andy Warhol, as well as her husband, the poet and artist, Willard Maas. Inspired by her existing accomplishments in abstract expressionistic painting, her cinematographical technique encompassed an exploration and violation of the traditional boundaries of the filmmaking process, through her spontaneity, grace and agility in the handling of a camera lens.

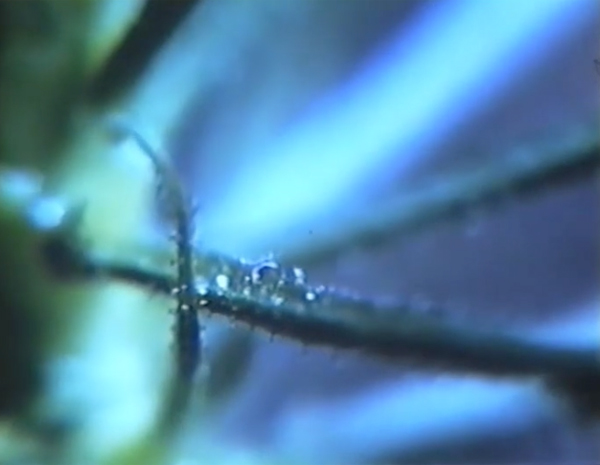

Photograph: © Marie Menken

… her hand-held camera directly capturing external light shaped into representational images on film is, at the same time, recording her whole body’s reaction to what she is seeing through that camera. She always tended, when taking pictures, to DANCE and, when editing those film strips, then, to capture the eye’s dance (rather than, say, some idealized stance-dance of the ‘mind’s eye’). She would hang up the strips and film and study the patterns, right, left, up, down, and splice them together as designs in Time—plenty of ideas arising in these arrangements of rhythmic Form, but no superimposed ideology.

—Stan Brakhage, Essential Brakhage

Glimpse of the Garden (1957), together with Arabesque for Kenneth Anger (1961), is my most favourite film in Menken’s exquisite body of work. Shot in a sumptuous summer’s garden on 16mm filmstock, the American filmmaker’s handheld movie is a simple visual poem accompanied by a soundtrack of chirruping birds. Reputedly, when Glimpse of the Garden was screened at the Cinemathèque Française in 1963, Jonas Mekas reported that the French audience laughed, embarrassed by the feature’s simple, childlike material.

Watching it now when confined to a small apartment with only the occasional houseplant for company makes me yearn to be utterly immersed in nature again, something I took for granted before the world was rife with pestilence and I had the liberty to go where I pleased. How quickly the course of humanity can change in the beat of a butterfly’s wing, the impact of which is brought into stark relief by the feelings evoked through participating in Menken’s beautiful film.

Photograph: © Marie Menken

Robert Breer, Stanley Brakhage and Marie Menken, thematically and formally represent, in the new American cinema, the best of the tradition of experimental and poetic cinema. Freely, beautifully, they sing the physical world, its textures, its colours, its movements; or they speak in little bursts of memories, reflections, meditations. Unlike the early avant-garde films, these films are not burdened by Greek or Freudian mythology and symbolism; their meaning is more immediate, more visual and suggestive. Stylistically and formally, their work represents the highest and purest creation achieved in the poetic cinema.

—Jonas Mekas, Notes on the New American Cinema

A flurry of floral colours, Glimpse of the Garden starts as a simple piece of footage in homage to an Arcadian paradise. More in the spirit of a home-movie, its introductory segments are no different from any other filmmaker’s attempts to capture the flora and foliage of a woodland estate, complemented by the avian melodies of birds.

As the film progresses, however, we witness a shift in perspective as Menken indulges in close-up compositions comprising stems and leaves and petals, the very components of the lush vegetation she is attempting to steal a glimpse. Curiously, this middle section morphs into the most glorious shades of blue—be it panning or static; crisply focussed or blurred—as her lens charts the inner territory of the secret lives of flowers. As the camera quite literally dances its way through the undergrowth, we remain captivated by the film’s understated simplicity, which harkens to a more fundamental truth; namely, how the fusion between the beauty of nature and the aestheticism of art opens our hearts and ennobles our very souls.

Photograph: © Marie Menken

The realist sees only the front of a building, the outlines, a street, a tree. Marie Menken sees in them the motion of time and eye. She sees the motions of heart in a tree … A rain that she sees, a tender rain, becomes the memory of all rains she ever saw; a garden that she sees becomes a memory of all gardens, all colour, all perfume, all mid-summer and sun.

—Jonas Mekas

Tiles of sunlight decorate the floor of my apartment. I can hear the silence of the warm sun through the crack in the window frame. Nature is oddly at peace whilst a despicable plague is simultaneously raging.

I think again of Tarkovsky’s words, how art directs us to discover the meaning of life. Somehow, finding significance in the midst of global pandemonium is oddly misplaced, perhaps; and yet, for those precious five minutes as I sat and watched Marie Menkin’s miniature masterpiece, I was transported to another realm, one which was more alive and real and meaningful, one which restored my faith and hope and belief in the destiny of mankind.

Rent Complete Films of Marie Menken

Post Notes

- Jean Cocteau: The Art of Cinema

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Michelangelo Frammartino: Le Quattro Volte

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth

- Marie Menken: Arabesque for Kenneth Anger

- Julian Schnabel: At Eternity’s Gate