Windows of the soul

“I have been fascinated by the Bible since my childhood;

the Bible is a synonym for Nature.”

—Marc Chagall

IT IS A typically English, dreary day in the parish of Tudeley, where I have come to view Marc Chagall’s stained glass masterpiece. For over a thousand years, All Saints’ has been a centre of Christian worship and is one of the oldest in the Weald of Kent. The building itself has been subject to many renovations over the centuries, with stonework sitting atop Saxon foundations, then eighteenth-century brickwork and finally a Victorian extension on the north aisle. Needless to say, it is the installation of Chagall’s glass art that has inspired my artistic pilgrimage.

Marc Chagall (born Moishe Shagal, 6th July 1887–28th March 1985) was a Russian French Jew and as such, his religious faith is intrinsic to understanding the message of his work. The Jews of Vitebsk, where Chagall was brought up, were Hasidim; that is, they followed a theological tradition stemming from the teachings of Baal Shem Tov, a mystic and healer who is regarded as the founder of Hasidic Judaism.

Essentially, the Hasidim believe that the whole of creation is fundamentally good, being an emanation of God. In order to access the virtuous, inner spark that burns at the very core of all living creatures, we must follow the way of love. By opening our hearts, we can mend dualistic separation, reuniting our essence with the divine. Chagall believed that the artist is similarly able to facilitate mystical union thereby awakening the inner soul. So what could be more befitting, in an attempt to combine both his spiritual beliefs and creative passion, than the commission with which he was entrusted to adorn All Saints’ Church?

The church’s transformation initially came about as a consequence of the tragic death of a twenty-one-year-old girl in 1963. Sarah Venetia d’Avigdor-Goldsmid was the eldest daughter of Sir Henry and Lady d’Avigdor-Goldsmid of Somerhill in Tonbridge, Kent. In September 1963, she and one of her companions died in a sailing accident off the coast of Rye in East Sussex.

Sir Henry was a professing Jew but Lady d’Avigdor-Goldsmid and their two daughters were Anglican and All Saints’ Tudeley was the church in which they worshipped. In the summer of 1961, Sarah and Lady d’Avigdor-Goldsmid had previously visited an exhibition at the Louvre featuring the work of Marc Chagall, the visual artist who was a pioneer of modernism and created work in almost every artistic medium, including fine art, ceramics, tapestries, book illustrations and, later in life, stained glass. Indeed, both women were enraptured with the great windows Chagall had designed for the synagogue of the Hadassah Medical Centre in Jerusalem, which were currently on display in Paris.

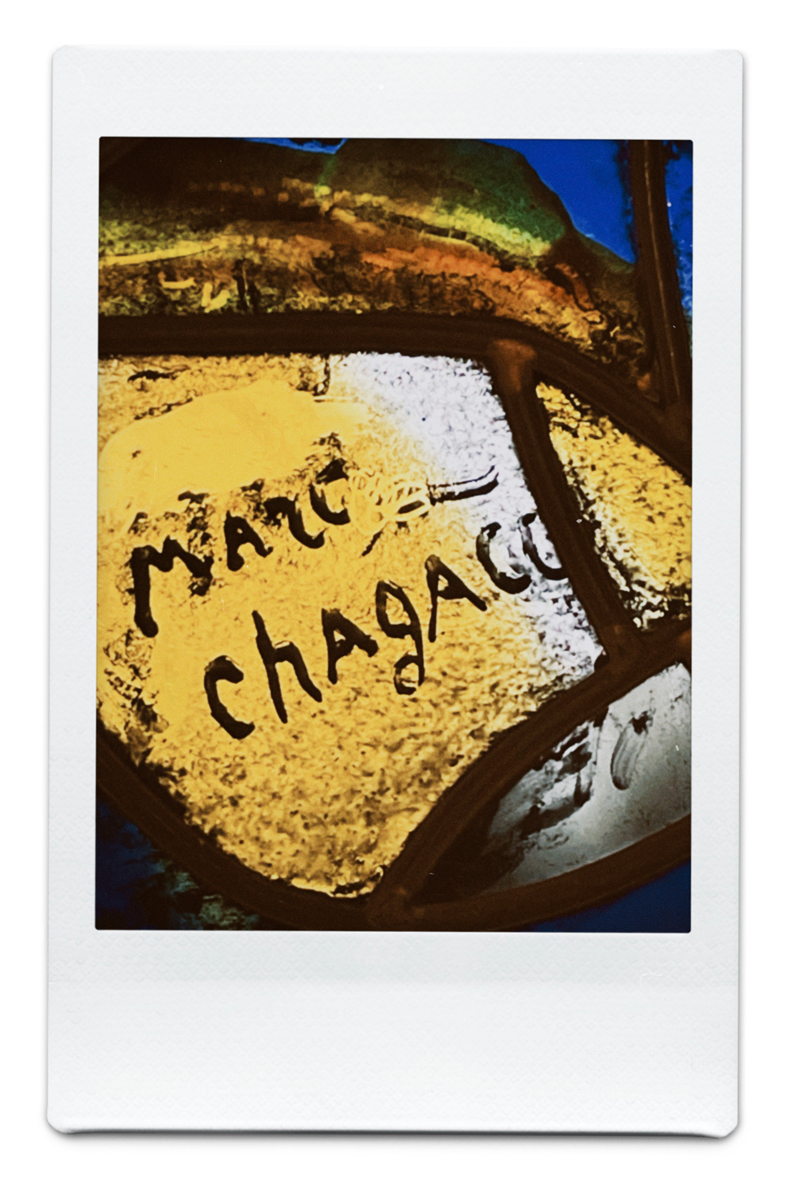

The recollection of Sarah’s admiration for Chagall’s stained glass became, therefore, the inspiration which led Sir Henry to commission Chagall to design a replacement memorial window in the east wall in order to commemorate her short life. Later, he would go on to authorize a further eleven windows to complete his overall vision, the beautiful designs transposed from Chagall’s sketches onto glass by Charles and Brigitte Marq of Atelier Jacques Simon in Reims, France.

After a series of delays and parochial wrangling lasting several years, the original Victorian windows were reordered into the vestry and all twelve windows were finally installed in situ, being inaugurated on 15th December 1985. Sadly, Chagall had already died on 28th March of the same year, coincidentally on the final day of the Royal Academy of Art’s Marc Chagall retrospective, where several of the chancel window panels destined for Tudeley were being exhibited.

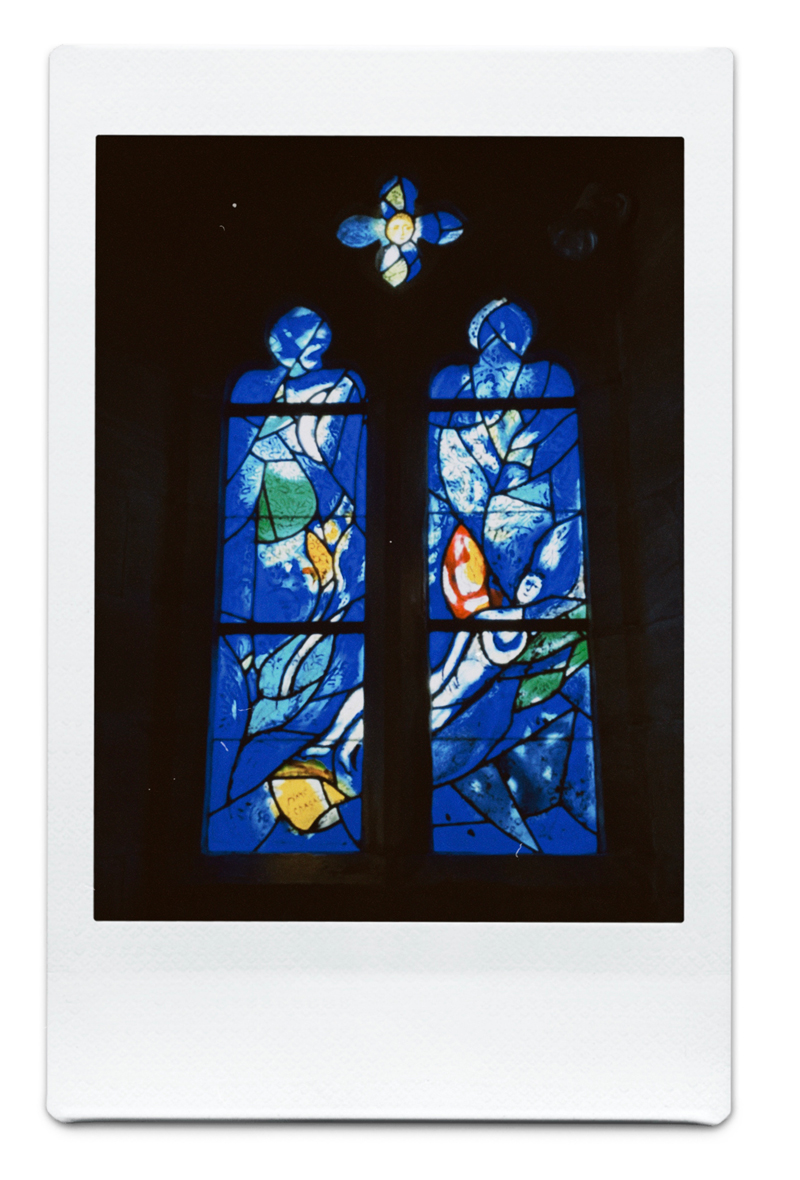

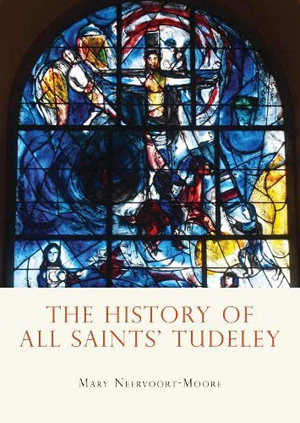

At first sight, the exterior of All Saints’ is unassuming and modest, located in a tranquil, rural landscape, once populated with hop gardens and apple trees. And yet, stepping through the south porch and leaving the dank, dull skies behind me, I am transported to another world, resplendent with light and colour and goodness. With Chagall’s memorial window dominating the east wall, I bear witness to a series of moving cameos featuring the drowned young woman, as well as the figure of Christ atop a ladder, represented not as a suffering saviour but as the Prince of Peace dispensing healing and love.

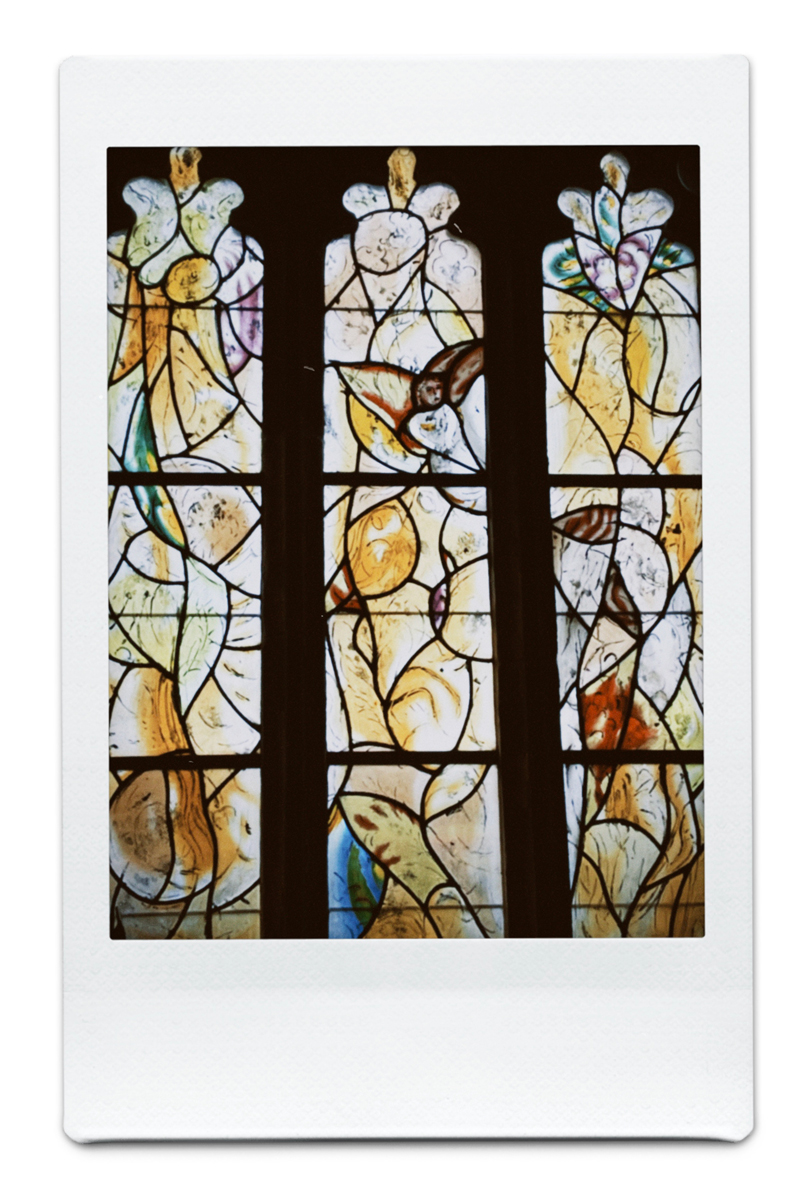

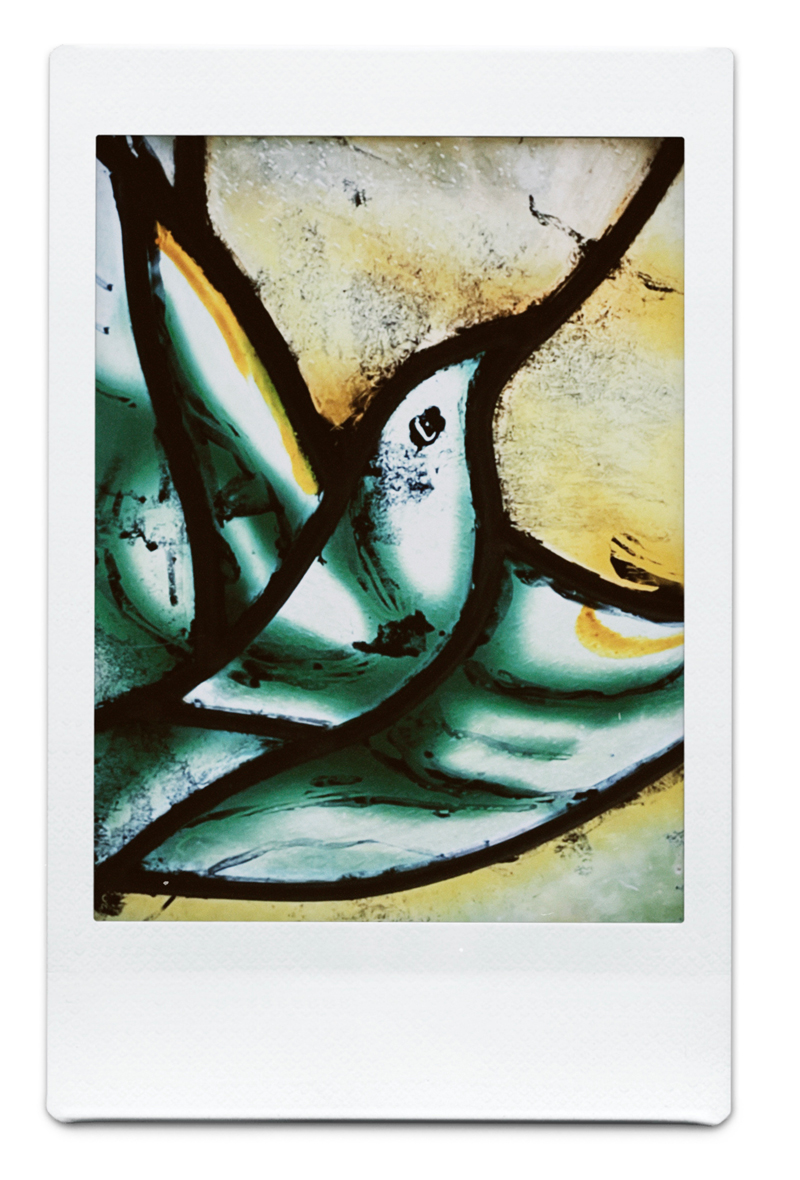

The remaining eleven windows present us with exquisite glimpses of the flora and fauna of the Bible—flowers, birds, butterflies, sea creatures, the moon … indeed the very fabric of the natural world, collectively illuminating All Saints’ Tudeley in cerulean, save for two windows in the nave that bathe the church in gold when the sun transits the south wall. It is truly a beatific vision to behold.

I then leave the church and sit in the sanctuary of the garden. Birdsong is the only sound I hear. The Kentish landscape stretches out before me into a virescent watercolour. I feel I could gladly sit here until the very end of my life.

Even the sky has assumed a poetic sensibility, its clouds blooming in Chagallian blue. My heart opens. I am at peace.

It has always seemed to me that the Bible was the greatest source of poetry of all time. The Bible is a resonance of Nature and this secret I have tried to transmit … These paintings, in my thoughts, represent not the dream of one people but of all humanity. Perhaps the young and the old will come into this house to seek an ideal of brotherhood and love, just as my colours and lines have dreamt it.

—Marc Chagall

Images: Paula Marvelly, All Saints’ Tudeley

(CC BY-SA 4.0) The Culturium