How individual belief triumphs over religious dogma

“And in praying use not vain repetitions, as the Gentiles do: for they think that they shall be heard for their much speaking. Be not therefore like unto them: for your Father knoweth what things ye have need of, before ye ask Him.”

—Matthew (vi. 7, 8)

THE THREE HERMITS by Leo Tolstoy (9th September 1828–20th November 1910) is one of those rare, perfectly formed tales conveyed in a simple, charming narrative, which manages to reveal the very profoundest of truths. As one of the greatest purveyors of the short story, Tolstoy was able to encapsulate completely his loathing of organized religion, in particular the Russian Orthodox Church for its sanctioning of social oppression, whilst presenting his own divine vision for the salvation of humankind.

The Russian novelist was a deeply spiritual man and saw it as his duty to write didactic literature in order to educate and illuminate his readers with a moralistic attitude to life. More specifically, after reading Arthur Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation, which advocates, amongst other things, that ascetic renunciation is the only true path to godliness, Tolstoy became fascinated with creating stories around the theme of holy poverty, The Three Hermits being the pinnacle of his quest.

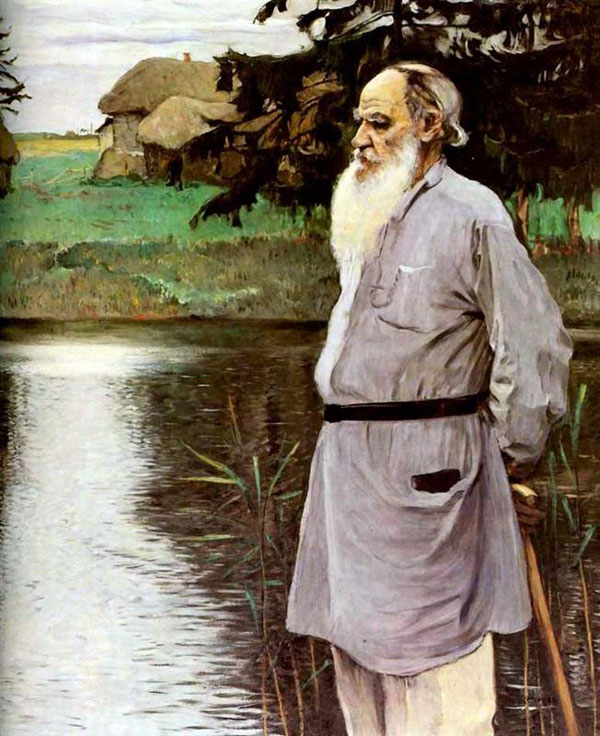

Mikhail Nesterov, Portrait of Leo Tolstoy.

Image: Public Domain

Drawing on Russian folklore and the theology of the Holy Trinity, we are introduced to a Bishop sailing on a ship between Arkhangelsk and the Solovetsky Monastery, accompanied by a number of fellow pilgrims. Upon overhearing a fisherman recount the tale of three hermits living on a small island, who once helped him repair his broken sailing boat, the curious Bishop makes further enquiries:

‘What hermits?’ asked the Bishop, going to the side of the vessel and seating himself on a box. ‘Tell me about them. I should like to hear. What were you pointing at?’

‘Why, that little island you can just see over there,’ answered the man, pointing to a spot ahead and a little to the right. ‘That is the island where the hermits live for the salvation of their souls.’

‘Where is the island?’ asked the Bishop. ‘I see nothing.’

‘There, in the distance, if you will please look along my hand. Do you see that little cloud? Below it and a bit to the left, there is just a faint streak. That is the island.’

The Bishop looked carefully, but his unaccustomed eyes could make out nothing but the water shimmering in the sun.

‘I cannot see it,’ he said.

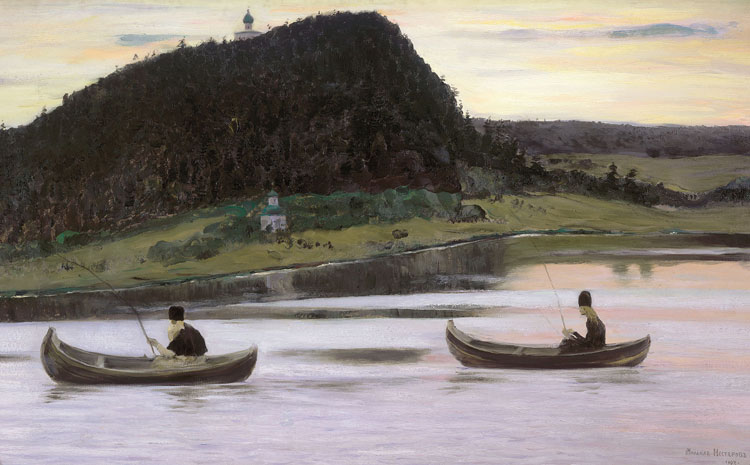

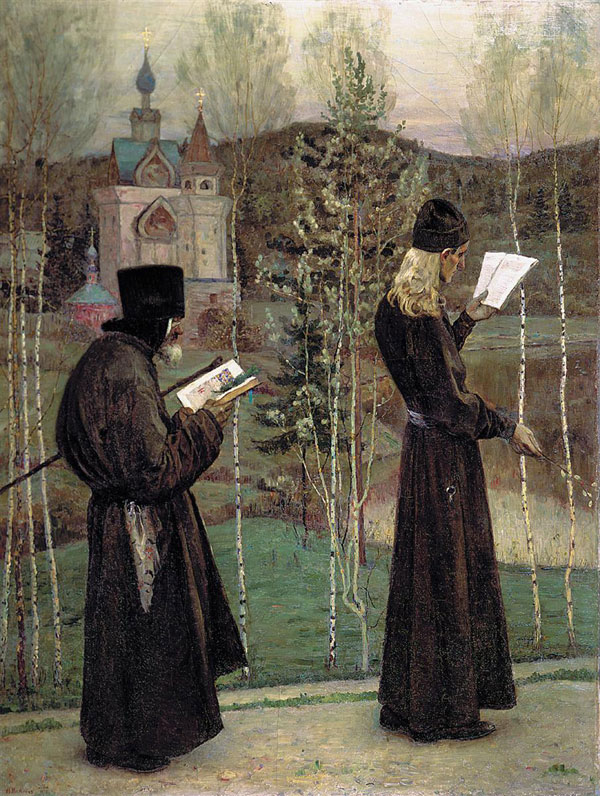

Mikhail Nesterov, Silence.

Image: Public Domain

Tolstoy very cleverly sets the scene for his tale: the simple peasant folk on board have no trouble viewing the island in the distance, albeit tiny and many miles yonder, and yet the Bishop is utterly incapable of seeing it for himself. Frustrated, he presses the fisherman further:

‘And what are they like?’ asked the Bishop.

‘One is a small man and his back is bent. He wears a priest’s cassock and is very old; he must be more than a hundred, I should say. He is so old that the white of his beard is taking a greenish tinge, but he is always smiling, and his face is as bright as an angel’s from heaven. The second is taller, but he also is very old. He wears a tattered, peasant coat. His beard is broad, and of a yellowish grey colour. He is a strong man. Before I had time to help him, he turned my boat over as if it were only a pail. He, too, is kindly and cheerful. The third is tall, and has a beard as white as snow and reaching to his knees. He is stern, with over-hanging eyebrows; and he wears nothing but a mat tied round his waist.’

Mikhail Nesterov, The Hermit.

Image: Public Domain

His curiosity piqued, the Bishop wants to know how they converse with each other and of what matters they discuss:

‘And did they speak to you?’ asked the Bishop.

‘For the most part they did everything in silence and spoke but little even to one another. One of them would just give a glance, and the others would understand him. I asked the tallest whether they had lived there long. He frowned, and muttered something as if he were angry; but the oldest one took his hand and smiled, and then the tall one was quiet. The oldest one only said: “Have mercy upon us,” and smiled.’

Immediately, the Bishop asks the ship’s captain to take him forthwith to the island so that he may meet the three illiterate hermits in person but his request is received with little enthusiasm:

‘… if I might venture to say so to your Grace, the old men are not worth your pains. I have heard say that they are foolish old fellows, who understand nothing, and never speak a word, any more than the fish in the sea.’

The Bishop is unperturbed and after offering money for his trouble, the captain, somewhat begrudgingly, makes the necessary preparations to take him ashore in a rowing boat.

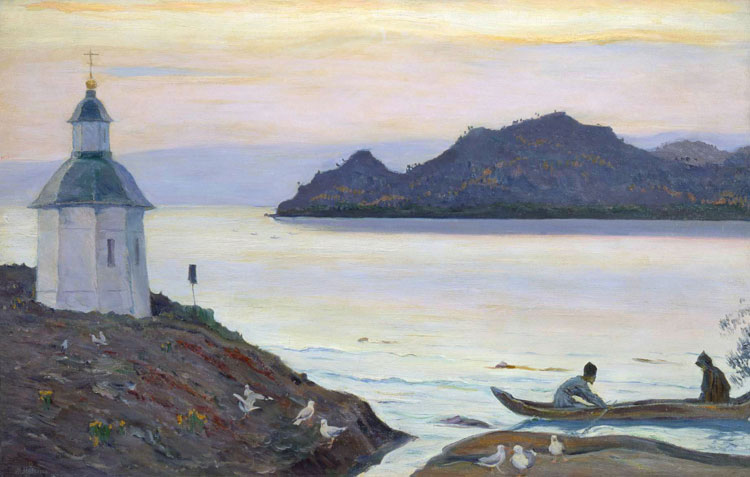

Mikhail Nesterov, Solovki.

Image: Public Domain

Setting afoot on the island, the Bishop is greeted by the three hermits who are exactly as described to him on deck—old and humble, with little to say. Without haste, he enquires of their spiritual practice, feeling it is his duty to offer religious counsel, being “an unworthy servant of Christ … called, by God’s mercy, to keep and teach His flock”:

The old men looked at each other smiling, but remained silent.

‘Tell me,’ said the Bishop, ‘what you are doing to save your souls, and how do you serve God on this island?’

The second hermit sighed, and looked at the oldest, the very ancient one. The latter smiled, and said:

‘We do not know how to serve God. We only serve and support ourselves, servant of God.’

‘But how do you pray to God?’ asked the Bishop.

‘We pray in this way,’ replied the hermit. ‘Three are ye, three are we, have mercy upon us.’

And when the old man said this, all three raised their eyes to heaven, and repeated:

‘Three are ye, three are we, have mercy upon us!’

Mikhail Nesterov, To Blagovest.

Image: Public Domain

Somewhat sanctimoniously, the Bishop praises their efforts and yet proceeds to inform them that there is a far better way to please God by reciting the Lord’s Prayer, which he then endeavours to teach them: “Our Father, who art in Heaven …” With much blundering and forgetfulness on the part of the hermits, the Bishop perseveres for many hours commanding them to repeat it over and over without prompting until they are word perfect.

As dusk descends, the Bishop is finally satisfied that he has performed his religious instruction to the best of his ability and the hermits are now better prepared to offer service to God:

It was getting dark, and the moon was appearing over the water, before the Bishop rose to return to the vessel. When he took leave of the old men, they all bowed down to the ground before him. He raised them, and kissed each of them, telling them to pray as he had taught them. Then he got into the boat and returned to the ship.

As the Bishop sits alone in the stern whilst the other pilgrims are sleeping, gazing out to sea under a starry cosmos, congratulating himself on performing his religious rites with perfect perfunctory piety, he spots a ghostly glimmer of light:

And the moonlight flickered before his eyes, sparkling, now here, now there, upon the waves. Suddenly he saw something white and shining, on the bright path which the moon cast across the sea. Was it a seagull or the little gleaming sail of some small boat? The Bishop fixed his eyes on it, wondering.

The shape of the apparition morphs into the three island hermits, running across the surface of the sea, “as if it were dry land”:

They saw the hermits coming along hand in hand and the two outer ones beckoning the ship to stop. All three were gliding along upon the water without moving their feet. Before the ship could be stopped, the hermits had reached it, and raising their heads, all three as with one voice, began to say:

‘We have forgotten your teaching, servant of God. As long as we kept repeating it we remembered but when we stopped saying it for a time, a word dropped out, and now it has all gone to pieces. We can remember nothing of it. Teach us again.’

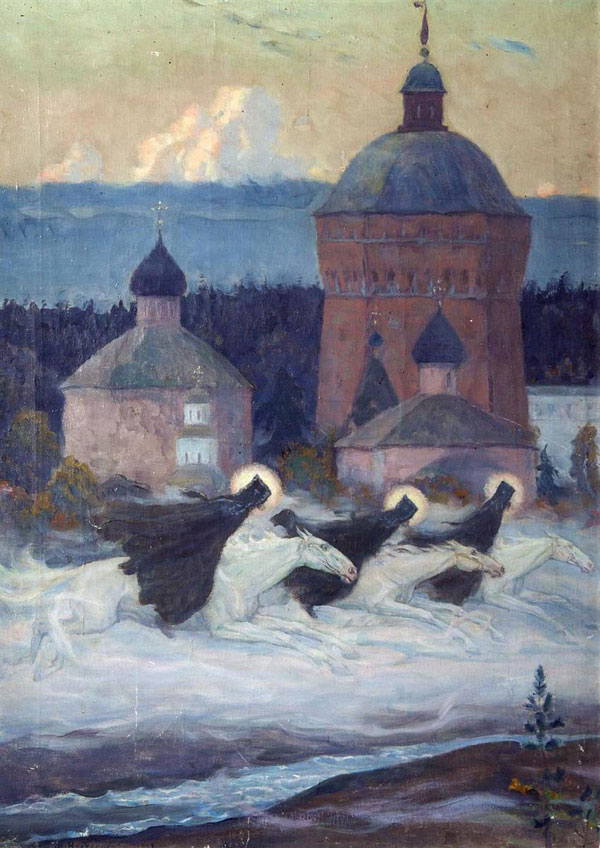

Mikhail Nesterov, Riders.

Image: Public Domain

The Bishop is stupefied by the miraculous vision and immediately realizes how his pious arrogance has blinded him to the humility of these simple eremitic men:

The Bishop crossed himself, and leaning over the ship’s side, said: ‘Your own prayer will reach the Lord, men of God. It is not for me to teach you. Pray for us sinners.’

And the Bishop bowed low before the old men; and they turned and went back across the sea. And a light shone until daybreak on the spot where they were lost to sight.

Tolstoy’s moral message is abundantly clear—the Bishop, representing the Orthodox Church of Russia (and, by extension, all Christian Churches) with its ostentatious, empty ritual, falls woefully short of the mystical depth and innate understanding of the humble eremite, exemplifying how authentic transformation and transcendence can only ever come from within.

Indeed, as with many of the Russian master storyteller’s compositions, The Three Hermits is a perfectly encapsulated magical fable pointing to a higher spiritual experience, faultlessly conceived and flawlessly composed.

Post Notes

- Feature image: Mikhail Nesterov, Hermit Fathers And Immaculate Women, Public Domain

- Leo Tolstoy’s official page on Facebook

- Leo Tolstoy: The Death of Ivan Ilyich

- Leo Tolstoy: A Confession

- E. M. Forster: The Celestial Omnibus

- Teresa of Ávila: The Ecstasy of Love

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- J. D. Salinger: Franny and Zooey

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme