How the fear of dying becomes a gateway

to the joy of living

“He would go to his study, lie down, and again be alone with It: face to face with It.

And nothing could be done with It except to look at It and shudder.”

A SHORT STORY that I have returned to many times, particularly when events in my life have been close to the brink, is the exquisite novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) by Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, better known as Leo Tolstoy (9th September 1828–20th November 1910). Considered to be one of Tolstoy’s greatest works and written after his religious conversion of the late 1870s, it is up there alongside War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

As the title suggests, Tolstoy’s masterpiece is a study of a man’s passing and yet it is far from the physical or even psychological kind. It is a meditation on the systematic collapse and ultimate annihilation of Ivan Ilyich’s fundamental identity and his futile struggles against It:

‘There was light but now there is darkness. I was here but now I am going. Where? … I shall be no more, then what will there be? There will be nothing. Then where shall I be when I am no more? Can this be dying? No, I will not have it!’

The tale is of a high-court judge, set in 19th-century Russia, who has risen up through the echelons of society to a point where he is leading a well-established and respectable professional life, despite the relentless antagonisms of his spouse. Now at the pinnacle of his career, Ivan Ilyich purchases an apartment in Saint Petersburg, lavishly decorating it with beautiful furniture, delicate ornaments and sumptuous wallpaper in every room.

Even the curtains are given his extra special attention; working in the Law Courts one day, his mind drifts away to pondering whether he should have straight or curved cornices with his living room drapes and other such conundrums of interior design. Life is good for Ivan Ilyich.

Then one day, mounting a stepladder in order to show a workman how he wants material to be adorned on the curtain rail, he slips and knocks his side against the knob of the window frame. The bruise is painful but he shrugs it off and continues about his daily tasks.

Soon, Ivan Ilyich develops a strange taste in his mouth and the pain in his side becomes unbearable. He sees a string of expensive physicians, all with their unique potions and prognoses, until he must face the reality and wretchedness of his situation—he is going to lose his life.

But Ivan Ilyich cannot accept his fate; he truly believes that he has lived a noble life and performed his civic duties diligently and without question. Had he been an irresponsible and reckless fellow, his suffering would have been justified. Ivan Ilyich can, therefore, make no sense of his physiological and mental anguish: “He wept at his own helplessness, at the cruelty of man, the cruelty of God, at the absence of God.”

His travails are further enhanced by the denial of his family to accept his plight, who prefer only to believe that he has been afflicted by a temporary malady from which he will soon recover. Only his manservant, Gerassim, a good-natured, local peasant boy, shows him any compassion for his suffering. Such authentic emotion, in the face of his family’s lack of human empathy, force Ivan Ilyich to consider whether he has, in fact, lived a good life or not.

Slowly he realizes that his life of social climbing, sycophancy, people politics has all been in vain: “In public opinion I was going up, and all the time my life was sliding away from under my feet … And now it’s all done and I must die.”

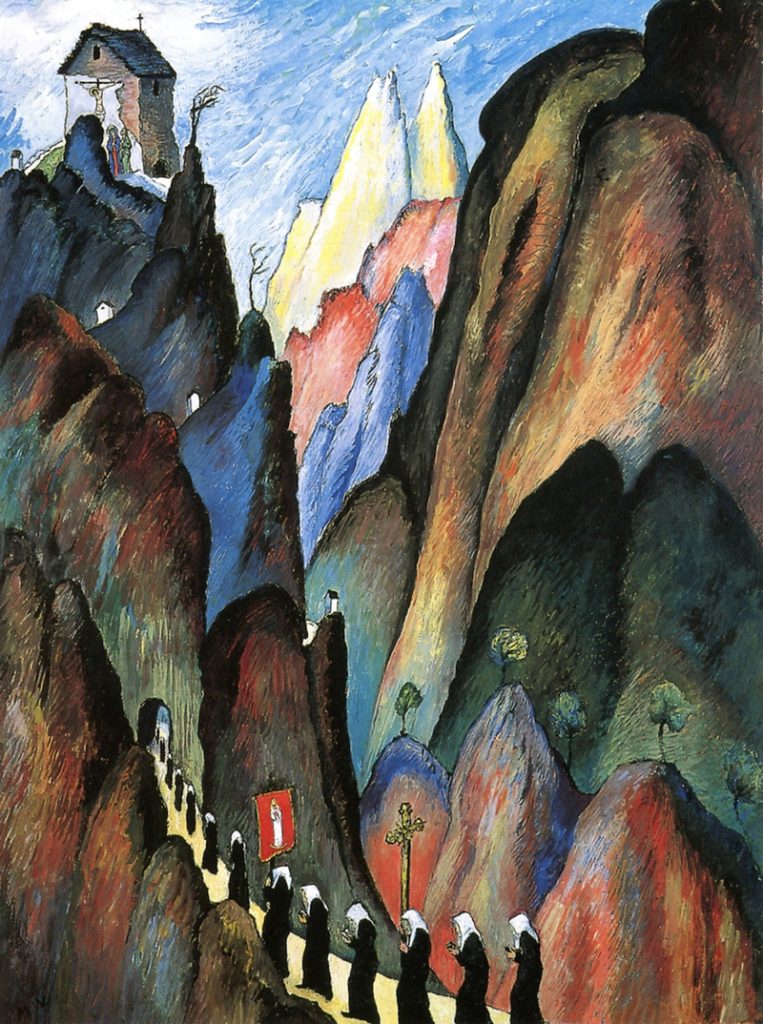

Marianne Werefkin, The Way of the Cross.

Image: Public Domain

The final three days in the life of Ivan Ilyich are filled with horror: “… he realized that he was lost, that there was no return, that the end had come, the very end.” Indeed, he screams so loudly that he can be heard through closed doors two rooms away. He realizes that his life has been a waste, that he has in fact lived a meretricious existence full of self-interest and self-pity, in contrast to the selfless, authentic life of Gerassim who seemingly takes everything in life, including death, in his stride.

On the third day, an hour before his demise, suddenly “… some force smote him in the chest and side, making it harder to breath; he sank through the hole and there at the bottom was a light.”

In the midst of his agony, he looks upon his wife and son and feels overwhelming compassion for them, for they must continue living their shallow, meaningless existence without any hope for peace or redemption. For Ivan Ilyich, however, in an instant, all pain and suffering have passed away, and he is bathed in epiphanic stillness:

‘Where are you, pain?’ He began to watch for it. ‘Yes, here it is. Well, what of it? Let the pain be. And death? Where is it?’ He searched for his former habitual fear of death and did not find it. ‘Where is it? What death?’ There was no fear because there was no death either. In place of death there was light. ‘So that’s what it is!’ he suddenly exclaimed aloud. ‘What joy!’

Someone nearby then whispers he thinks it is all over:

He caught the words and repeated them in his soul. ‘Death is over,’ he said to himself, ‘It is no more.’ He drew in a breath, stopped in the midst of a sigh, stretched out and died.

Post Notes

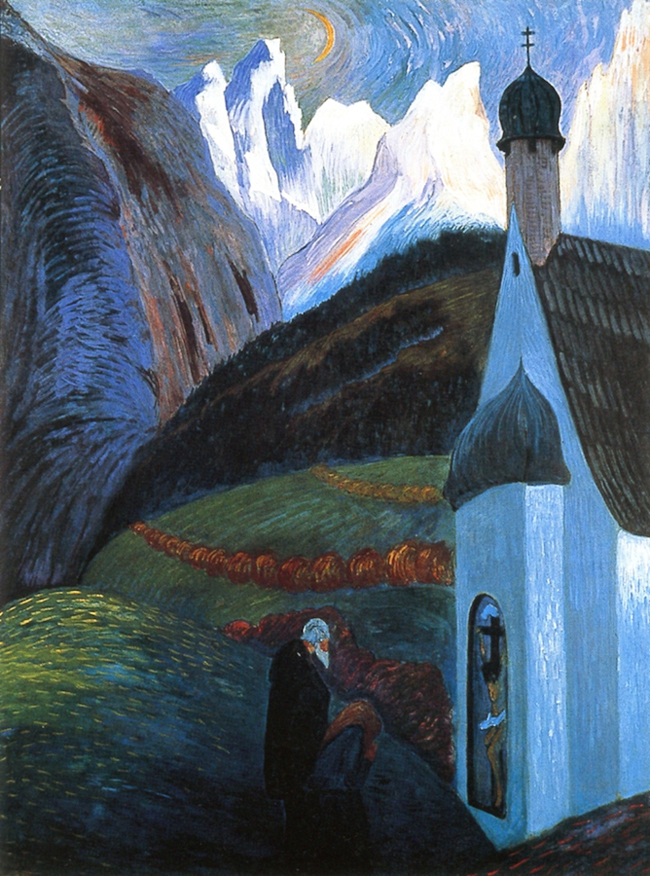

- Feature image: Marianne Werefkin, Prayer, Public Domain

- Arseny Tarkovsky: Life, Life

- Leo Tolstoy: The Three Hermits

- Leo Tolstoy: A Confession

- Seneca: On Tranquillity of Mind

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Nature

- Michel de Montaigne: On Solitude

- Rousseau: Meditations of a Solitary Walker

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Waldeinsamkeit

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme