The Immeasurable, Is God an Invention of Thought? | J. Krishnamurti

Religious mind

“When you listen attentively,

in that attention there is no you attending.

You are listening.

Not that you are listening,

there is only the act of listening.”

LEAH LUONG has a B.A. in Political Science (Global Politics) from California State University, Long Beach. She has been involved in the dissemination of Krishnamurti’s teachings with the Krishnamurti Foundation of America for many years after attending a retreat in Ojai. Raised amongst communities of dogmatic institutions and groups, her interest in questioning the truth from a young age was inevitable.

In a compelling essay for this month’s guest post on The Culturium, Leah outlines the core principles of Krishnamurti’s nondual philosophy, complemented by the words of the great (non) teacher himself in the beautifully produced short film, Is God an Invention of Thought?, courtesy of The Immeasurable, a project of the Krishnamurti Educational Centre, dedicated to exploring the essential questions of our existence.

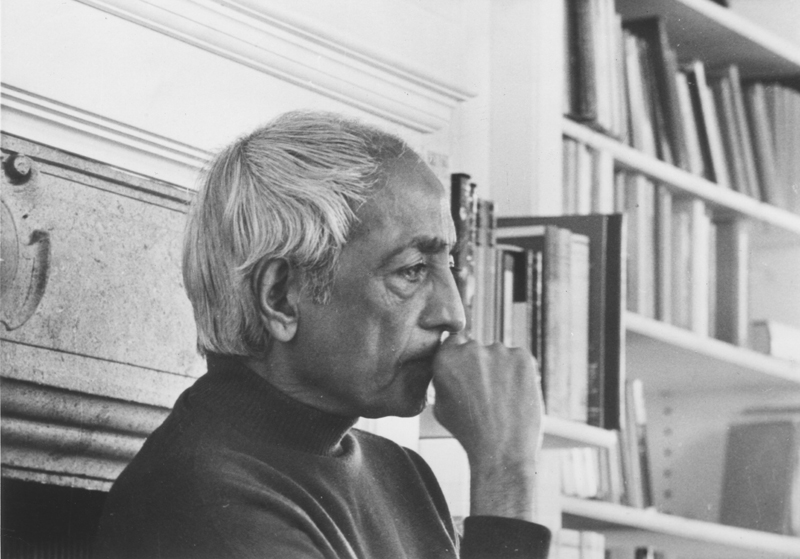

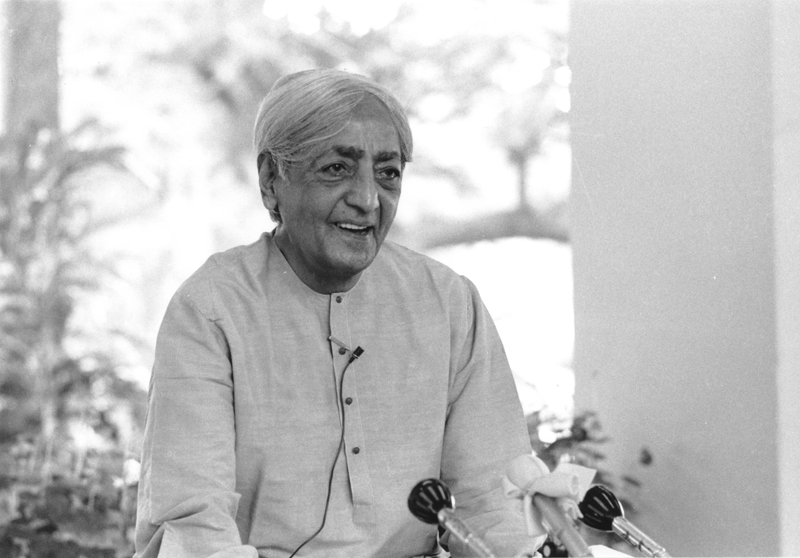

Photograph: © Krishnamurti Foundation of America

Jiddu Krishnamurti (11th May 1895–17th February 1986) was a philosopher, speaker and writer. In 1911, the Theosophical Society created an organization called the Order of the Star to proclaim the coming of the “World Teacher”. Krishnamurti was made head of this organization and groomed to be this Teacher. Eighteen years later in August 1929, Krishnamurti dissolved the Order before 3000 members.

His dissolution speech started with what many consider one of his most popular quotes:

I maintain that Truth is a pathless land and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect. That is my point of view and I adhere to that absolutely and unconditionally. Truth, being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever, cannot be organized; nor should any organization be formed to lead or to coerce people along any particular path. If you first understand that, then you will see how impossible it is to organize a belief. A belief is purely an individual matter and you cannot and must not organize it. If you do, it becomes dead, crystallized; it becomes a creed, a sect, a religion, to be imposed on others. This is what everyone throughout the world is attempting to do. Truth is narrowed down and made a plaything for those who are weak, for those who are only momentarily discontented. Truth cannot be brought down, rather the individual must make the effort to ascend to it. You cannot bring the mountain-top to the valley. If you would attain to the mountain-top you must pass through the valley, climb the steeps, unafraid of the dangerous precipices.

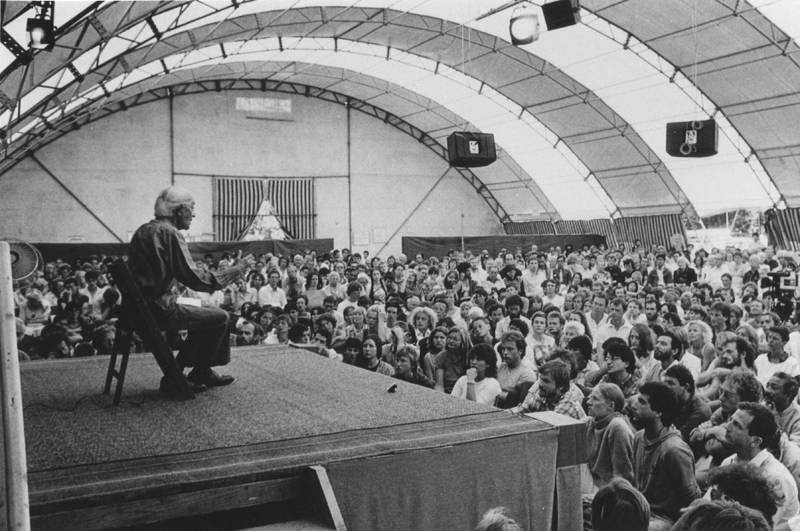

Photograph: © Krishnamurti Foundation of America

Krishnamurti asserted that organizations like these are barriers to understanding—crutches that stunt one’s growth and the discovery of truth—and suggested that organizations should act as a tool, similar to how one uses a computer. One can use a computer to perform computations but doesn’t put it on an altar and worship it. Nevertheless, this is what human beings have been doing throughout history. Despite impressive technological advancements, humanity is still psychologically primitive; the society we have created, and are part of, is conflicted, violent and brutal. It makes one wonder, what is religion or God? Is it believing that something or someone else has the key to freedom or happiness? Humanity is split into different religions and beliefs—each with its own methods, systems and rules. One can see how this division is enforced in religions and organizations in which there are those “who know” and those “who don’t know”, always requiring authority or an interpreter to gain so-called salvation or liberation.

Does this division have anything to do with the mind? Krishnamurti stated that what we call God and religion are actually things (concepts) put together by thought. Perhaps the reason why humans have organized religion is because it’s a way for thought to attempt to manage, solve and control. For example, controlling the fear of uncertainty or solving the desire to belong. It appears to us that we’ve done something to fix the internal issues we face by believing in a certain God, preaching non-violence, or donating 10% of our income to the church but are these activities simply temporary ameliorations—good enough for now until there’s a disturbance in the psyche and we go on repeating the cycle? It makes sense why we do this: thought is useful and necessary for solving issues like driving a car to get home from work, using a computer and building a rocketship. It is clear that thought is needed for practical matters.

Yet, when it comes to the psychological realm, thought doesn’t seem to be able to end our inner problems like sorrow, conflict or envy. In fact, when attempting to solve these issues, we might actually be moving farther away from the ending of them. Krishnamurti implied that thought itself is limited and can’t be used to truly end psychological matters. However, thought doesn’t appear to be limited to us; another one of Krishnamurti’s most well-known quotes, “the observer is the observed”, illustrates how what we often think of as observation is actually another fragment of thought acting. Thought, which has put together the entire content of our consciousness, is conditioned and the limitations of accumulated knowledge inevitably bring about conflict and division.

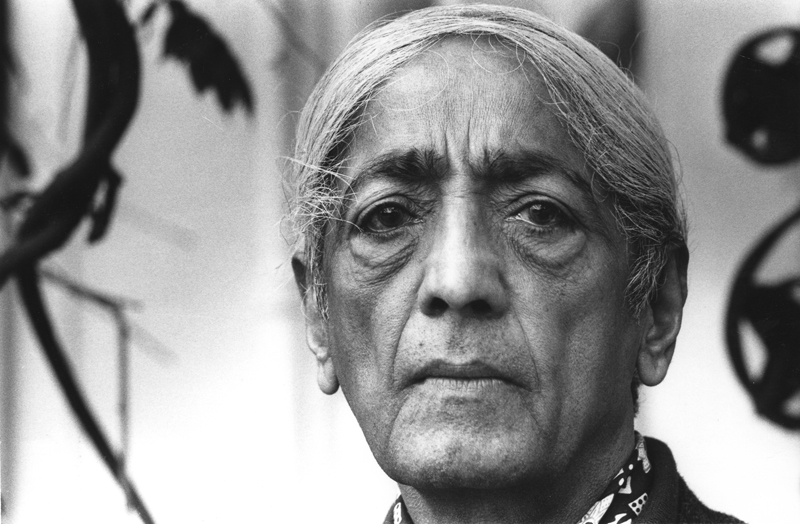

Photograph: © Krishnamurti Foundation of America

Are things like loneliness and sorrow actually separate from us or are they brought about by the self-centred activities of thought? We see problems as external as if something like fear is happening to us. Krishnamurti invites his listeners to ponder if something like fear or envy might actually be part of us. That is, envy is something created by thought and thought is the creator of the self-centre or the “me”/ “I”. He suggests that seeing our feelings, desires and fears as separate from us creates conflict: then we try to avoid, suppress or do something about it. He says, “You are not separate from your face, from your name, from your bank account, from your values, from your experience, from your knowledge—you are all that. So, when one realizes this truth, that you are not separate from that which you feel, which you desire, which you want, which you pursue, which you fear, there is no conflict.” If all these things are not separate from me, then what else is there to do about it other than stay with it? Krishnamurti said that it is like holding a precious jewel: you keep looking at it, watching it and playing with it—and then there’s a sense of release, freedom. Could this sense of release come from not wasting energy on trying to analyse or escape that which we are?

We seem to have been taught how to discipline and control ourselves but if that’s true then why is there still so much disorder both inwardly and outwardly? The word “discipline”, which derives from “disciple”, means “one who learns, not who imitates, not who conforms, but one who is learning”. What would it mean to learn together; does it imply we are both the teacher and the taught? How does one even begin to understand oneself? It may not be a question of “how” but in asking if one can see the movements of self-centred activity. Krishnamurti emphasized finding out for oneself, not just twisting his words to fit our way of thinking and to enquire about the nature of ourselves. Is it possible to look without authority, not according to an expert but to truly discover the truth of the matter? Can one look at “what is” without trying to modify it so that something totally new could occur?

Krishnamurti states that one must look into the content of our consciousness: “Our beliefs, our experiences, our faith, doubt, questioning, desires, superstitions, fears, pleasures, the great agony of loneliness, suffering and what we call love, which has become merely sexuality, sensory pleasures; and the religious enquiry, if there is something beyond all the manifestations of thought, if there is something utterly untouched by thought, something sacred, holy, which doesn’t belong to any religion.” Here he appears to be speaking about a type of looking or a quality of mind that is entirely free from the field of the known, from time itself.

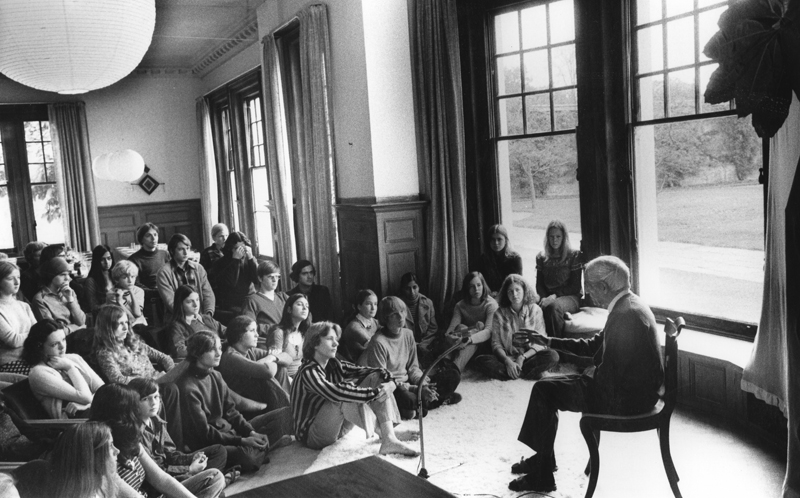

Photograph: © Krishnamurti Foundation of America

Enquiring without the known could mean staying with what we would normally try to control or move away from. It may also mean enquiring with no motive to become enlightened, achieve something or arrive somewhere else—all of which are coming from a centre or the “me”. If one realized that thought continues to create a series of escapes that ultimately maintain conflict and division, could there be listening without motive or the desire to immediately step in and change something? Krishnamurti says, “When you listen attentively, in that attention there is no you attending. You are listening. Not that you are listening, there is only the act of listening.”

Meditation means attention, not that we are the ones doing the attending, so that there is no longer the self-centred activity of thought. The true depth of meditation has no measure, time or thinking; there is a profound, enduring stillness that emanates from it. From this listening, there is silence without the self or thought imposing something on the brain. He says that this is not a man-made silence, rather it is a silence that has no cause. This silence contains “that which is nameless, which is beyond all time—such a mind is a religious mind”.

Without thought getting in the way and causing conflict, it could be that humanity has a chance to come into direct contact with what we really are. It’s not that thought doesn’t exist, it’s just seen as a movement of the mind. In truly seeing what we are, perhaps one could see the danger of division: nationalism, wars, beliefs, politics and the many ways humans separate themselves from one another. The “religious mind” Krishnamurti points to might be describing a mind that is free to find out what the truth is, a mind that isn’t burdened by experience and doesn’t reach back in memory to see what it already knows because we are limited by what we think we know. This quality of mind is free and has the potential to bring about a new society and end conflict, fear, hurt and the various psychological divisions that have always plagued humanity.

Photograph: © Krishnamurti Foundation of America

Post Notes

- Brockwood Park School

- The Krishnamurti Centre

- Krishnamurti Foundation Trust

- Krishnamurti Foundation of America

- The Immeasurable

- Krishnamurti’s Notebook