Photograph: © Kindai Eiga Kyokai

Silent sea

I am interested in man, the solitary person, who is placed in the midst of chaotic surroundings, and when I try to grasp and unfold the problems of society which surround him, I have to know what is within man himself. I cannot escape from looking more closely into what is the essence, the root existence of man.

—Kaneto Shindo

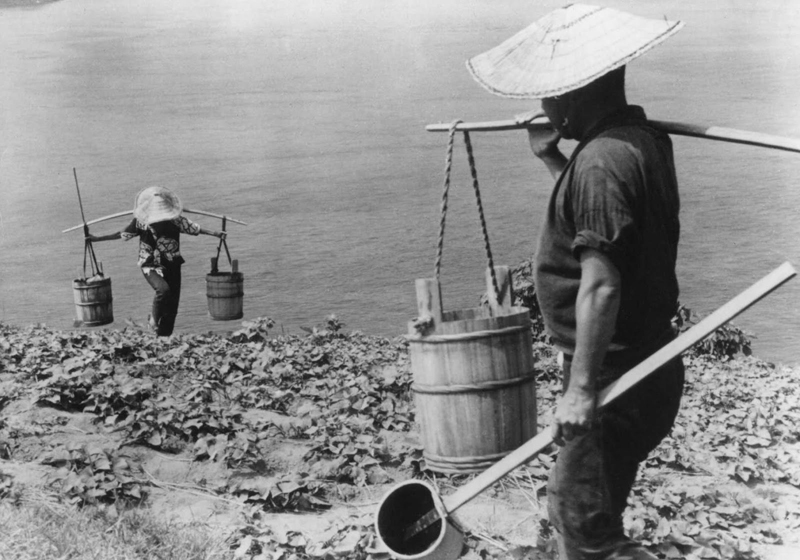

THE NAKED ISLAND (裸の島 or Hadaka no shima), written and directed by Japanese auteur, Kaneto Shindo (22nd April 1912–29th May 2012), is an elegiac masterpiece. Filmed on the tiny island of Sukune in the Seto Inland Sea located in the Hiroshima Prefecture, a man and his wife, together with their two young sons, mete out their harsh existence by cultivating a crop of sweet potatoes, for which they relentlessly have to fetch fresh water in buckets from a mainland well, rowing back and forth several times a day, Sisyphean, in order to sustain their isolated and meagre way of life.

In the tradition of the “slow cinema” championed by directors such as Andrei Tarkovsky, Yasujirō Ozu, Robert Bresson, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Béla Tarr and Ben Rivers, The Naked Island is presented as a fusion between a black and white documentary-styled melodrama and a “moving image” arthouse feature. With minimal dialogue and a haunting musical score by avant-garde composer, Hikaru Hayashi, the overall effect is a uniquely poignant and exquisitely beautiful meditation on what it means to be a human being, set against a backdrop of extreme poverty and hardship, counterpointed by a visually stunning landscape.

Released in 1960, the film’s silent portrait of twentieth-century peasant life can be viewed both as a timeless mythological tale about the human condition, as well as a critical exposition on the emergent capitalist culture of modern-day Japan. When tragedy strikes, the insular family are devastated but such is the weight of their suffering, they are effectively stupefied to overt displays of grief, impeccably performed by lead actors, Taiji Tonoyama and Nobuko Otowa, mistress and then wife of Kaneto Shindo. (Interestingly, both Otowa and Shindo’s ashes were scattered on Sukune upon their respective deaths.)

Photograph: © Kindai Eiga Kyokai

I was interested in the ‘image’. To me ‘imagery’, with its deep associations and imaginative richness, provides a powerful, eloquent medium. Filmmaking is one form of visual imagery, and also an art. I was deeply interested in creating within this art form. In Japan, there is a proverb, which says, ‘the eye can express as much as the mouth can.’

—Kaneto Shindo

Photograph: © Kindai Eiga Kyokai

I consider melodrama to be a story or situation created artificially, with the sole purpose of attracting an audience’s attention. This is contrived very conveniently. If you want to depict a truthful drama, it is permissible to use any means available … However, this is the area in which true artists are separated from professional craftsmen. If the director, the ‘creator’, intends to produce a truly artistic work, he must carefully choose the most suitable dramatic situation from the many possibilities. This selection is in the director’s hands entirely and the choice determines how fine an artist he is.

—Kaneto Shindo

Photograph: © Kindai Eiga Kyokai

I should like to point out here first I am an artist, not a politician, so I do not see the class struggle as it appears in the political arena. I like to see and describe it as it affects the individual human being, in his daily life. I like to look into the political and class struggle with the eyes of an objective artist. It is easy to view social conflict with political idealism or at least with the tainted eyes of political desire. I strive to avoid this by all means. After all, struggles are endemic to our society as it is. I am saying that with an artist’s eyes, I would like to see problems as they face working people who are the protagonists in my films. I am interested in the way they overcome their difficulties; at least I like to evoke the hope of overcoming, some prospect for the future.

—Kaneto Shindo

Post Notes

- Matsuo Bashō: The Narrow Road to the Deep North

- Jean Cocteau: The Art of Cinema

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Michelangelo Frammartino: Le Quattro Volte

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth

- Marie Menken: Arabesque for Kenneth Anger

Join Our Newsletter