Portrait of a Woman With a Winged Bonnet.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

How love is the only meaning to life

“All shall be well, and all shall be well

and all manner of things shall be well.”

BEING A NOBODY in a society obsessed with prestige and prosperity is a challenging position; and yet embracing a state of utter nothingness, renouncing the clutter of worldly possessions and the preoccupation with social status, can, in fact, be a totally liberating experience. One such woman, who embraced the concept to its acme, found not only “the all and the everything” in individual oblivion but also that it was nourished and sustained by the power of love.

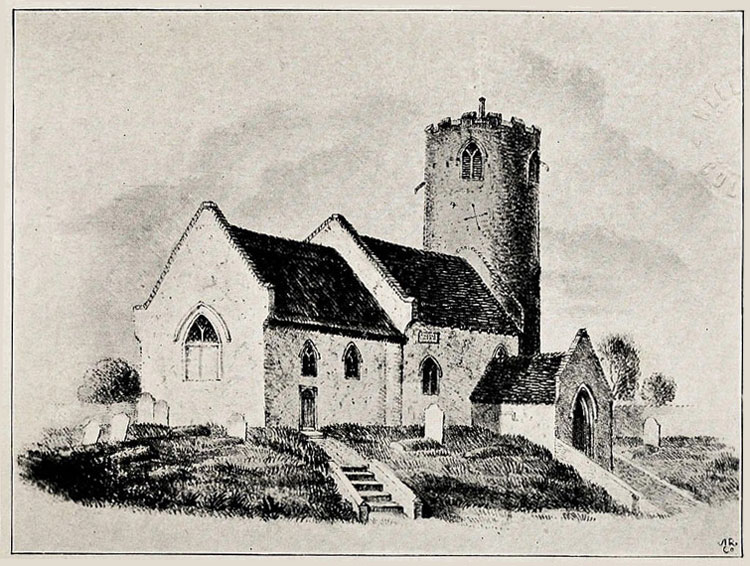

Julian of Norwich (her real identity is unknown) was born in December 1342 into a wealthy family and educated at boarding school attached to Carrow Abbey nunnery. It is not clear when she took ecclesiastical orders but she chose to live her life as an anchoress (deriving from the Greek word meaning “to retire”), whereby she was literally entombed in a sealed cell attached to St. Julian’s Church in Norwich, forsaking all the trappings of the material world.

Although her daily needs, such as food and firewood, would have been attended to by a servant, she had effectively chosen to die unto the world, in order to focus her attention exclusively on her interior existence.

It would be in her early thirties whilst at home, in a similar manner to Sri Ramana Maharshi, that Julian was struck down by an acute illness on 8th May 1373, subsequently lasting for nearly a week, which brought her to the brink of death. During this harrowing time, she received a total of sixteen “showings” or visions of the Passion of Jesus Christ, and which would lead her towards the eremitic life.

After a miraculous recovery, she set about recording her visions as the Revelations of Divine Love. Some twenty years later, she rewrote the entire text, expanding the narrative and adding commentary and theological reflection. Thus, the Short Text was composed in 1373 and the Long Text in roughly 1393:

And when I was thirty-and-a-half years old, God sent me a bodily sickness in which I lay for three days and three nights; and on the fourth night I received all the rites of the Holy Church and did not believe that I would live until morning. And after this I lingered on for two days and two nights. And on the third night I often thought that I was dying, and so did those who were with me.

But at this time I was very sorry and reluctant to die, not because there was anything on earth that I wanted to live for nor because I feared anything, for I trusted in God, but because I wanted to live so as to love God better and for longer, so that through the grace of longer life I might know and love God better in the bliss of heaven.

And yet all is ultimately well and Julian makes a full recovery:

Then I truly believed that I was at the point of death. And at this moment all my suffering suddenly left me, and I was as completely well, especially in the upper part of my body, as ever I was before or after. I marvelled at this change, for it seemed to me a mysterious work of God, not a natural one.

A woman of her times, Julian would have been acutely aware of the misogynistic message of her male clerical colleagues, as well as the legacy of Saint Paul, who demanded that all women should “remain silent in the churches”, amongst other acts of submission. Nevertheless, despite proclaiming how uneducated and humble she is, Julian defiantly defends her right to speak:

God forbid that you should say or assume that I am a teacher, for that is not what I mean, nor did I ever mean it; for I am a woman, ignorant and frail … Just because I am a woman, must I therefore believe that I must not tell you about the goodness of God, when I saw at the same time both his goodness and his wish that it should be known?

Once again, Julian writes with the familiar metaphor of divine lovers, harking back to the mystical relationship explored in the immortal Song of Songs, in an attempt to convey her feelings of devotion and awe. As the embodiment of love, Christ is Julian’s beloved—through their divine marriage, the two become one:

And in this binding and union he is a real and true bridegroom, and me his loved bride and his fair maiden, a bride with whom he is never displeased; for he says, I love you and you love me, and our love shall never be divided.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Appearing only in the Long Text, when she presumably had more time to develop the idea, she cleverly juxtaposes the authoritarian portrayal of Father God, more associated with fear and punishment, against the protective personification of Mother Christ, all nurturing and all forgiving:

And so our Mother, in whom our parts are kept unparted, works in us in various ways; for in our Mother, Christ, we profit and grow, and in mercy he reforms and restores us, and through the power of his Passion and his death and rising again, he unites us to our essential being. This is how our Mother mercifully acts to all his children who are submissive and obedient to him.

As Christ’s children, we return to his “motherhood” for our support and sustenance. Moreover, Julian is also reinforcing the mediaeval idea that milk was reprocessed blood. Christ’s bleeding on the Cross is, therefore, seen as the nourishing love of the Mother—feeding us, sustaining us and uniting us in his milky care.

And similar to Hildegard of Bingen, Julian is further blessed with a vision of the entire universe who, together with all the mystics before her, is made to understand that everything that exists is a manifestation of God:

And in this vision, he showed me a little thing, the size of a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, and to my mind’s eye it was as round as any ball. I looked at it and thought, ‘What can this be?’ And the answer came to me, ‘It is all that is made.’ I wondered how it could last, for it was so small I thought it might suddenly disappear. And the answer in my mind was, ‘It lasts and will last forever because God loves it; and in the same everything exists through the love of God.’

In this little thing I saw three attributes: the first is that God made it, the second is that he loves it, the third is that God cares for it. But what does this mean to me? Truly, the maker, the lover, the carer; for until I become one substance with him, I can never have love, rest or true bliss; that is to say, until I am so bound to him that there may be no created thing between my God and me.

What is striking about Julian is her capacity to rationalize her visions into a comprehensive philosophical argument. Despite her nondual explanation of the cosmos, it still perplexes her; contemplating this paradox, she asks her Lord how sin could exist if he were responsible for all that was made. Echoing the mystical message of the Gnostic Gospels, she writes:

And after this I saw God in an instant, that is to say, in my understanding, and in seeing this I saw that he is in everything. I looked attentively, knowing and recognizing in this vision that he does all that is done. I marvelled at this sight with quiet awe, and I thought, ‘What is sin?’ For I saw that God does everything, no matter how small. And I saw that truly nothing happens by accident or luck, but by the eternal providence of God’s wisdom.

Therefore I was obliged to accept that everything which is done is well done, and I was sure that God never sins. Therefore it seemed to me that sin is nothing, for all this vision no sin appeared.

Julian explains further that God compels us to suffer in order to test our love and make us humble. And yet, as her Lord reiterates, everything is as it should be and in what has become one of her most enduring lines, quoted centuries later by T. S. Eliot in his beautiful poem, Four Quartets, she explains:

It is true that sin is the cause of all this suffering, but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

God is our Mother as truly as he is our Father; and he showed this in everything, and especially, in the sweet words where he says, ‘It is I,’ that is to say, ‘It is I: the power and goodness of fatherhood. It is I: the wisdom of motherhood. It is I: the light and grace which is all blessed love. It is I: the unity. I am the sovereign goodness of all manner of things. It is I that make you love. It is I that make you long. It is I: the eternal fulfilment of all true desires.

God is omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent. And knowledge of this fact is most important:

… all men and woman who wish to lead the contemplative life need to have knowledge of it; they should choose to set at nothing everything that is made so as to have the love of God who is unmade. This is why those who choose to occupy themselves with earthly business and are always pursuing worldly success have nothing here of God in their hearts and souls: because they love and seek their rest in this little thing where there is no rest, and know nothing of God, who is almighty, all wise and all good, for he is true rest.

God wishes to be known, and is pleased that we should rest in him; for all that is below him does nothing to satisfy us. And this is why, until all that is made seems as nothing, no soul can be at rest. When a soul sets all at nothing for love, to have him who is everything that is good, then it is able to receive spiritual rest.

Furthermore, in the manner of German mystic, Meister Eckhart, she elegantly elucidates the rendering of oneself unto nothing in order to become everything and all with God:

For if I look at myself, I am really nothing; but as one of mankind in general, I am in oneness of love with all my fellow Christians; for upon this oneness of love depends the life of all who shall be saved; for God is all that is good, and God has made all that is made, and God loves all that he has made.

Everything that God wills for us is owing to his love. And this is what Julian finally comes to understand some fifteen years later after the initial sequence of showings in one final revelation, a few years prior to composing the Long Text:

‘Do you want to know what your Lord meant? Know well that love was what he meant. Who showed you this? Love. What did he show? Love. Why did he show it to you? For Love. Hold fast to this and you will know and understand more of the same; but you will never understand or know from it anything else for all eternity.’ This is how I was taught that our Lord’s meaning was love.

Julian lived until her mid-seventies, although the date of her death is unknown; similarly, the place of her burial is also a mystery. And yet hers is a legacy that will never be forgotten, her showings one of the most profound and most impassioned religious testaments ever written, not least by the fairer sex.

Indeed, through her intellectual rigour and poetic expression, she joins the great canon of sacred feminine literature, empowering those who wish to die unto the world and are reborn in the divinity of love.

Post Notes

- The Julian Centre

- Teresa of Ávila: The Ecstasy of Love

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- Alexandra David-Néel: My Journey to Lhasa

- T. S. Eliot: A Man Out of Time

- Gospel of Mary Magdalene

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Kathleen Raine: The Land Unknown

- Michael Molinos: The Spiritual Guide