Photograph: Public Domain

Come, oh come …

I shall die as most will die;

the rake will pass through my life

And comb my name back into the soil.

Light, speechless, childless,

I shall stare weary-eyed at the barren sky.

—Gertrud Kolmar

SHORTLY AFTER GRADUATING from the Royal College of Music in 1975, Julian Marshall’s professional life as an English composer and songwriter took flight with the internationally successful bands Marshall Hain, The Flying Lizards and Eye to Eye. His compositions include work for film and theatre as well as a new chapter as a composer of longer-form work, together with other shorter, choral-based pieces. In addition to composition, Julian teaches and coaches creatives of all ages. He works with clients privately and is also a Teaching Fellow at ICMP, London.

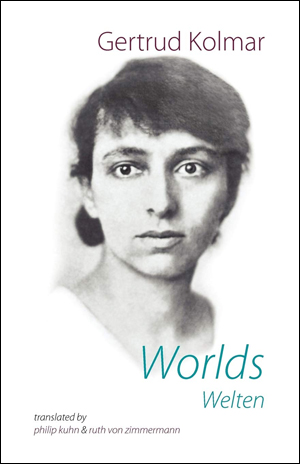

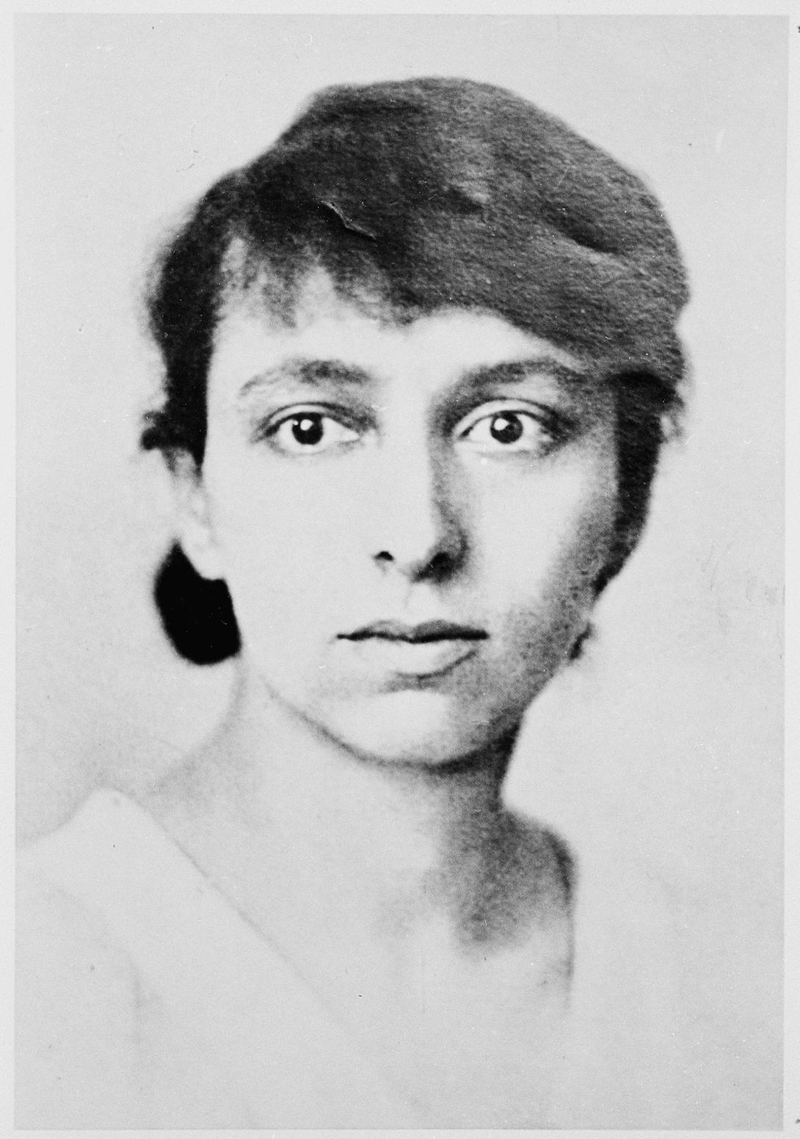

The Welten Project is the inclusive title for compositional works either inspired by, reimagined or the literal setting of poems from Welten, a 17-poem cycle by Gertrud Kolmar, the obscure German-Jewish writer and poet, who was deported and then perished en route to Auschwitz. In this month’s guest post for The Culturium, Julian tells the story of the project’s inception and growth into a growing body of work.

o0o

The above quotation, taken from the German-Jewish poet Gertrud Kolmar, was what I read back in November 2007, which woke me out of a long creative slump and back into action—and in such a way, so I thought, that I was neither expecting nor seeking.

The occasion was that of visiting my cousin, Kate, and her husband, Philip, in Winchester, shortly after their return from a visit to the Jewish Museum in Berlin. They brought back a museum guide. I picked it up, flicked through and found myself stopped in my tracks by Kolmar’s quote. I don’t even know why. The quote is beautiful but “stopped in my tracks”?

Something sparked deep inside me and, before I left for home, I had determined not just to find out all I could about this poet of which I’d never heard but to set one of her poems as a cantata for solo soprano, two cellos and small choir: exactly the kind of attached, over-intentional thinking I’d generally advise my students to avoid at all costs! So, who was Gertrud Kolmar and how come I’d never heard of her before?

Philip Kuhn, one of the two translators for her last collection of poems under the title, Welten (translated as Worlds), wrote a short biographical note about her (abridged here), taken from his full-length essay on the life and work of Gertrud Kolmar to mark the world premiere of my cantata, Out of the Darkness:

Gertrud Chodziesner was born on 10th December 1894 into a Jewish family in Berlin. After training as a teacher, she worked with orphaned and disadvantaged children until an ill-fated love affair with a non-Jewish army officer resulted in an abortion and subsequent suicide attempt.

After the Armistice in 1918, she found work as a private tutor and governess until the autumn of 1927, when she attended a vacation course at Dijon University. But her time in France was curtailed when she was obliged to return home to nurse her mother. Following her mother’s death in March 1930, Gertrud assumed full-time responsibilities for the family household in Finkenkrug, an idyllic rural suburb of Berlin.

While living in Finkenkrug, Gertrud (under the pen name Kolmar) composed nearly all her important literary works including eight cycles of poetry [including Welten].

In July 1941, Gertrud was conscripted to a munitions factory. Just over a year later, her father was deported to Theresienstadt and finally, in late February 1943, Gertrud herself was arrested and deported to Auschwitz, where, had she managed to survive the nightmare journey east, she would have been selected, on arrival, for immediate extermination.

—Philip Kuhn, His Countenance is Sorrow: Some Thoughts on the Life and Work of Gertrud Kolmar Together with Three Translations from Welten

If it weren’t for Swiss-domiciled family members managing to smuggle much of Gertrud’s work out of Germany, we would almost certainly know nothing about her life and work at all. As it is, she still remains far less internationally known and acknowledged than some of her contemporaries—Nelly Sachs, Miklós Radnóti, Primo Levi and Else Lasker-Schüler, for example.

As I started to find translations of her work and read more about her life, I found myself becoming deeply drawn into this extraordinary woman’s world—her 1937 Welten cycle stood out to me as an especially compelling body of work. Whatever the themes explored in each of the “worlds”, each poem seemed to be suffused with a pregnant sense of mystery, soulfulness and intrigue. I was quickly hooked!

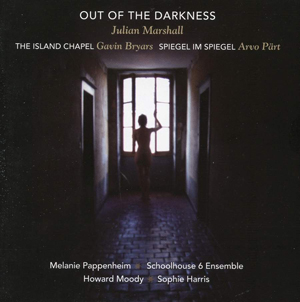

I soon decided to set the poem, “Aus dem Dunkel” (in English translation), as the main text for a work that became the cantata, Out of the Darkness. The poem evokes powerful, dreamlike images and strange visions. A visceral sense of uncertainty, crumbling and decay arise as the protagonist continues on her journey through the city and out into the mountains. A feeling of deep ill-ease saturates the mood—surely, an eerie foretelling of the imminent tidal wave of horror about to hit the world.

Here are the first two stanzas from the poem:

Out of the darkness I come, a woman,

I carry a child but no longer know whose;

Once I knew it.

But now no man is for me anymore …

They all have trickled away like rivulets,

Gulped up by the earth.

I continue on my way.

For I want to reach the mountains before daybreak and the stars are beginning to fade.Out of the darkness I come.

Through dusky alleys I wandered alone,

When, suddenly, a charging light’s talons tore the soft blackness,

The wild cat, the hind,

And doors flung open wide, disgorged ugly screams, wild howls, beastly roar.

Drunkards wallowed …

I shook all this from the hem of my dress along the way.—Gertrud Kolmar, My Gaze Is Turned Inwards: Letters 1934–1943, “Out of the Darkness”

Out of the Darkness was premiered in Winchester Cathedral on 19th March 2009, with soprano Melanie Pappenheim, cellists Sophie Harris and Lucy Railton, together with the Schoolhouse 6 Ensemble, conducted by Howard Moody. Later that year, we toured, recorded and published the piece on CD and streaming platforms.

Julian Marshall, Out of the Darkness

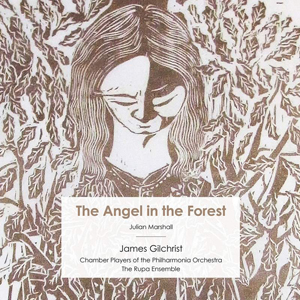

It wasn’t long before I set about composing a second piece, also setting text from Welten, now much aided by a new translation of the entire cycle by Philip Kuhn and Ruth Von Zimmermann. The featured poem for this work was “Der Engel im Walde” (“The Angel in the Forest”), which became a second cantata, this time written for the tenor, James Gilchrist, small chorus and cello sextet.

In this poem, the tone is exceptionally bleak. There is little, if any, hope offered as the protagonist and her partner flee and attempt to find solace in … “the musing fields, which congenially console our roaming feat with flowers and grass … to the animals of the forest who don’t speak evil.”

The angel they then encounter is a being … “tall and slender, without wings. His countenance is sorrow. And his robe has the pallor of icy, gleaming stars in winter nights.” Here is an angel who appears impotent—unable to fly, unable to do what angels must surely do best: inspire, bless and offer a certain portal into the realms of mystery, the sacred, the heavenly.

The text continues: “The being, who does not say, nor should, who just is, who knows no curse, brings no blessings and does not surge into cities, towards that which dies. He does not behold us in his silver silence, but we behold him, because we are two and forsaken.”

During the time Kolmar was writing Welten, she and her father had been forced to leave their beautiful home in Finkenkrug and move into cramped, shared accommodation in the centre of Berlin—a flat where any sense of the once certain privacy became a thing of the past: “Come with me, my friend, come. The stairs in my father’s house are dark and crooked and narrow and the steps are worn; but now it is the house of the orphan and strangers live in it. Take me away.”

And from here on, the poem shifts into a declaration, a plea that the ambiguous (or even mysterious) “you” character in the poem becomes her home. It is a powerful transition:

The old rusty key in the gate hardly obeys my feeble hands.

Now it creaks shut.

Now look at me in the darkness, you, from today my home.

Because your arms shall build me sheltering walls,

And your heart will be my chamber and your eye my window through which the morning shines.

And the forehead towers up as you stride.

You are my house on all the streets of the world, in every valley, on every hill.

You roof, you will thirst wearily with me under sweltering midday, shiver with me when snow storm whips.

We will thirst and hunger, suffer together,

Together, one day, sink down by the dusty wayside verge and weep …—Gertrud Kolmar, Worlds, trans. Philip Kuhn and Ruth Von Zimmermann, “The Angel in the Forest”

The Angel in the Forest received its first full premiere at St James’s Church, Piccadilly on 21st January 2012, with James Gilchrist (soloist), Sophie Harris (leading the cello sextet) and the Schoolhouse 6 Ensemble (chorus), with Ian Belton conducting. I was also thrilled when in last autumn we were able to record the piece with James Gilchrist, a cello sextet comprising players from The Philharmonia Orchestra and singers from The Rupa Ensemble.

Julian Marshall, The Angel in the Forest

Below is a short introductory film in which James Gilchrist and I talk about the The Angel in the Forest and the Welten Project.

Julian Marshall, The Angel in the Forest

After writing The Angel in the Forest, my composing interests diversified and further Kolmar works were set aside while I pursued other compositional interests. The first lockdown of 2020, however, presented me with the opportunity to thoroughly re-appraise my creative intentions and one particular result of this was a reanimation of my commitment to developing new Kolmar pieces. Collaborating with some remarkable creative partners, 2022 saw two new Welten Project works come to fruition. The first of these was the film project, Yearning.

Yearning is a danced-inspired reimagination of the poem of the same name and a collaboration with choreographer Daisy Brodskis, dancer Hannah Rudd, cinematographer Miguel Altunaga, poet Emily Louise Bland and soprano Miranda Ostler.

Here is the poem in its entirety and I invite you to read it first before watching the film:

I think of you,

I think of you always.

People spoke to me, but I didn’t take heed.

I looked into the deep Chinese blue of the evening sky from which the moon hung as a round yellow lantern,

And mused upon another moon, yours,

Which became for you the dazzling shield of an ironical hero, maybe, or the soft golden discus of an exalted thrower.

In the corner of the room I sat then without lamplight, day weary, veiled, given entirely to the darkness,

The hands lay in the lap, my eyes fell shut.

But onto the inner septum of the eyelids was painted your picture small and blurred.

Under stars I strode past quieter gardens, past the silhouettes of pine trees, shallow silenced houses, steep gables

Under soft funereal coat, which was only occasionally seized by wheel grinding, tugged by owl screech,

And I talked silently of you, beloved, to the noiseless, to the white almond-eyed dog, which I led.Engulfed nights, drowned in everlasting seas!

When my hand bedded itself in the down of your chest to slumber,

When our breaths blended into an exquisite wine, which we offered to our Goddess, Love, in a rose quartz bowl,

When in the mountains of darkness the druse grew and ripened for us, hollow fruit of rock crystals and lilac amethysts,

When the tenderness of our arms called fiery tulips and porcelain blue hyacinths from wide undulating earth reaching into dawn,

When, playing on twisted stem, the half opened bud of the poppy like a viper flicked blood-red over us,

Balsam and cinnamon trees of the east lifted themselves round our bed with quivering leaves

And crimson weaver finches intertwined our mouth’s breath into floating nests.

When will we flee again into the secret’s forests, which, impenetrable, shelter hind and deer from the pursuer?

When will my body be again white fragrant bread for your hungry beseeching hands, the split fruit of my mouth be sweet to your thirsting lips?

When will we encounter each other again?

Strew heartfelt words like seeds of aromatic herbs and summer flowers

And fall silent happier, so as to hear the singing sources of our blood?

(Beloved, do you feel my small listening ear resting on your heart?)

When will we glide again in the barque under lemon-coloured sail,

Rocked blissfully by silver foamed dancing wave,

Past palms adorned by a green turban like the scion of the prophet,

Towards the fringe reefs of distant islands, coral reefs, on which you want to founder?

When again, beloved, … when again … ? …

Now my path sinters

Through wasteland. Thorn scratches the foot.

Streams, cool, refreshing waters, murmur; but I don’t find them.

Dates swell, which I don’t taste. My starving soul

Mutters one word only, this one:

‘Come …’

Oh come …—Gertrud Kolmar, Worlds, trans. Philip Kuhn and Ruth Von Zimmermann, “Yearning”

Julian Marshall, Yearning—A re-imagination of the poem by Gertrud Kolmar

Ekphrasis (when a work of art in one medium is “translated” into that of another medium—a picture or a ceramic pot into the form of a poem, for example) and the reimagination of an already existing piece of work are creative pursuits that interest me greatly. They open up an opportunity, which I can only express as a kind of special intimacy: moving into the space of another’s world, another’s experience, another point of view. At worse, this can occur as an intrusion, an invasion, an appropriation. At best, it can do nothing less than evoke a sense of uniting our shared human experience across cultures, space and time. An expression of love. It’s a delicate matter.

Creating Yearning as a collaboration and a reimagination was a most interesting process. We took the view, here, that we would not attempt to translate the poem at all but rather to work with certain themes that the poem clearly evokes. Director Daisy Brodskis says in her brief synopsis: “Ebbing and flowing between torment and bliss, the longing for fulfilment, unrequited. Yearning is not as simple as a recall of memory or a ‘want’. There is, in yearning, both truth and fantasy. Time holds no weight. It merges ecstasy and agony in a dream-nightmare-like state. But whilst carrying this, we might find ourselves resigned to simply pulling back into ‘ordinary’ life as we continue along our path.”

… My starving soul

Mutters one word, only this one:

‘come …’

Oh come …

Photograph: © Jamie Wright

Garden in Summer is an EP project scheduled for release in April/May 2023. It is another collaboration—this time with performer, Avigail Tlalim, director, Anastasia Bruce-Jones and poet, Emily Louise Bland. The EP comprises four spoken-word tracks and a re-mix instrumental.

A particular feature of this suite of pieces is that it includes both a reading/performance of the original Welten poem, “Garden in Summer”, and also readings/performances of three specially written poetic reimaginations of the original poem by Emily Louise Bland.

This new way of working (for me), integrating spoken word with music, offers a really exciting new direction and potential for future work. I am hopeful of some live showings of Garden in Summer later in the year.

So, why Kolmar? Why Welten?

The Welten cycle presents a compelling opportunity for creating work of reimagination and ekphrasis—plus, in addition, acts as a springboard and inspiration for wholly original work. Despite being written in 1937, Kolmar’s Welten cycle offers a body of work of remarkable universality and abundant resonance with our world today.

Indeed, Art’s remarkable ability to evoke the multi-hued ambiguities of experience, to lay bare the “radical mystery of existence”, as J. F. Martel puts it in his Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice, speaks to qualities that, in my view, become immediately recognizable in Kolmar’s work—and throw down a most compelling gauntlet to any artist or composer following in her wake.

Post Notes

- Julian Marshall’s website

- Emily Dickinson: A Woman Before Her Time

- Sappho: The Tenth Muse

- Ana Ramana: Hymns to the Beloved

- Arvo Pärt: Silentium

- John Cage: Silence

- John Adams: The Dharma at Big Sur

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- Joep Franssens: Harmony of the Spheres

- Hans Otte: The Book of Sounds

- John Tavener: Towards Silence

Join Our Newsletter