Art and contemplation

Man’s ability to see is in decline. Those who nowadays concern themselves with culture and education will experience this fact again and again. We do not mean here, of course, the physiological sensitivity of the human eye. We mean the spiritual capacity to perceive the visible reality as it truly is.

To be sure, no human being has ever really seen everything that lies visibly in front of his eyes. The world, including its tangible side, is unfathomable. Who would ever have perfectly perceived the countless shapes and shades of just one wave swelling and ebbing in the ocean! And yet, there are degrees of perception. Going below a certain bottom line quite obviously will endanger the integrity of man as a spiritual being. It seems that nowadays we have arrived at this bottom line.

—Josef Pieper, Only the Lover Sings, “Learning How to See Again”

IN THE CORRESPONDENCE between Screwtape, under-secretary to the devil, and his nephew, Wormwood, instructing him in the most expedient ways to tempt the followers of the Enemy, namely Jesus Christ, he writes, “Music and silence—how I detest them both!” Indeed, as Josef Pieper, German Catholic philosopher (4th May 1904–6th November 1997) makes clear in his exquisite collection of essays, Only the Lover Sings, in which he extols all the creative arts as well as making reference to C. S. Lewis’ satirical, epistolary tract, The Screwtape Letters, it is the act of seeing that must be similarly lauded as being on a par with the auditory realm for its divinatory effects on the human soul.

I am writing this on my return from Canada, aboard a ship sailing from New York to Rotterdam. Most of the other passengers have spent quite some time in the United States, many for one reason only: to visit and see the New World with their own eyes. With their own eyes: in this lies the difficulty. During the various conversations on deck and at the dinner table, I am always amazed at hearing almost without exception rather generalized statements and pronouncements that are plainly the common fare of travel guides. It turns out that hardly anybody has noticed those frequent small signs in the streets of New York that indicate public fallout shelters. And visiting New York University, who would have noticed those stone hewn chess tables in front of it, placed in Washington Square by a caring city administration for the Italian chess enthusiasts of that area?!

Or again, at table, I had mentioned those magnifcent fluorescent sea creatures whirled up to the surface by the hundreds in our ship’s bow wake. The next day it was casually mentioned that ‘last night there was nothing to be seen’. Indeed, for nobody had the patience to let the eyes adapt to the darkness. To repeat, then: man’s ability to see is in decline.

—Josef Pieper, Only the Lover Sings, “Learning How to See Again”

Comprising five short essays, two in particular— “Learning How to See Again” and “Three Talks in a Sculptor’s Studio: Vita Contemplativa” —move me the most profoundly. There is something deeply evocative about reading the reflections of a thoughtful thinker whilst embarking upon a seafaring voyage, one in which time seemingly stands still and where, owing to the physical confinement with minimal outward distraction, one is forced to delve deep into the recesses of oneself and truly see that which arises both without and within.

Searching for the reasons, we could point to various things: modern man’s restlessness and stress, quite sufficiently denounced by now, or his total absorption and enslavement by practical goals and purposes. Yet one reason must not be overlooked either: the average person of our time loses the ability to see because there is too much to see!

There does exist something like ‘visual noise’, which just like the acoustical counterpart, makes clear perception impossible. One might perhaps presume that TV watchers, tabloid readers and moviegoers exercise and sharpen their eyes. But the opposite is true. The ancient sages knew exactly why they called the ‘concupiscence of the eyes’ a ‘destroyer’. The restoration of man’s inner eyes can hardly be expected in this day and age—unless, first of all, one were willing and determined simply to exclude from one’s realm of life all those inane and contrived but titillating illusions incessantly generated by the entertainment industry.

—Josef Pieper, Only the Lover Sings, “Learning How to See Again”

Despite being written in 1950, Josef Pieper’s words are a manifesto for the current time, one in which we are surfeited with digital stimuli rendering us totally desensitized to all visual form. Drawing on the writings of Plato and Thomas Aquinas and their reflections on beauty and aesthetics, his elegant meditations on daily living are an antidote to our consumerist culture, hell-bent on being stimulated by as much optical static as possible.

The capacity to perceive the visible world ‘with our own eyes’ is indeed an essential constituent of human nature. We are talking here about man’s essential inner richness—or, should the threat prevail, man’s most abject inner poverty. And why so? To see things is the first step toward that primordial and basic mental grasping of reality, which constitutes the essence of man as a spiritual being.

I am well aware that there are realities we can come to know through ‘hearing’ alone. All the same, it remains a fact that only through seeing, indeed through seeing with our own eyes, is our inner autonomy established. Those no longer able to see reality with their own eyes are equally unable to hear correctly. It is specifically the man thus impoverished who inevitably falls prey to the demagogical spells of any powers that be.

—Josef Pieper, Only the Lover Sings, “Learning How to See Again”

Reminiscent of the Zen artist, Frederick Franck’s invocation to employ the “awakened eye” of conscious experience, Josef Pieper implores us to see things as they truly are, without the veil of judgement, lethargy or disaffection rendering us impecunious in the process. Only when the inner vision of the mystic illumines our perception can there ever be immunity from the clutches of a diabolical force, dragging us below the “bottom line” unto the subterranean depths of delusion and darkness.

Nobody has to observe and study the visible mystery of a human face more than the one who sets out to sculpt it in a tangible medium. And this holds true not only for a manually formed image. The verbal ‘image’ as well can thrive only when it springs from a higher level of visual perception. We sense the intensity of observation required simply to say, ‘The girl’s eyes were gleaming like wet currants.’ (Tolstoy).

Before you can express anything in tangible form, you first need eyes to see. The mere attempt, therefore, to create an artistic form compels the artist to take a fresh look at the visible reality; it requires authentic and personal observation. Long before a creation is completed, the artist has gained for himself another and more intimate achievement: a deeper and more receptive vision, a more intense awareness, a sharper and more discerning understanding, a more patient openness for all things quiet and inconspicuous, an eye for things previously overlooked. In short: the artist will be able to perceive with new eyes the abundant wealth of all visible reality, and, thus challenged, additionally acquires the inner capacity to absorb into his mind such an exceedingly rich harvest. The capacity to see increases.

—Josef Pieper, Only the Lover Sings, “Learning How to See Again”

And therein lies the very heart of all authentic artistic endeavour: the capacity to transcend egoic agenda and drink deeply from the archetypal pool of creativity that unites all of humanity—nourishing, inspiring and uplifting us from within. Only then can a work of art truly impart meaning and profundity because it was initially forged by the touch of a higher hand.

The distinguishing and characterizing element in the artistic creativity we celebrate today lies, as I am convinced, in this: we witness an expression of the contemplative life, the vita contemplativa … to contemplate means first of all to see—and not to think!

The true artist, however, is not someone who simply and in any way whatever ‘sees’ things. So that he can create form and image (not only in bronze and stone but through word and speech as well), he must be endowed with the ability to see in an exceptionally intensive manner. The concept of contemplation also contains this special intensified way of seeing. A twofold meaning is hereby intended: the gift of retaining and preserving in one’s own memory whatever has been visually perceived. How meticulously, how intensively—with the heart, as it were—must a sculptor have gazed on a human face before being able, as is our friend here, to render a portrait, as if by magic, entirely from memory! And this is our second point: to see in contemplation, moreover, is not limited only to the tangible surface of reality; it certainly perceives more than mere appearances. Art flowing from contemplation does not so much attempt to copy reality as rather to capture the archetypes of all that is. Such art does not want to depict what everybody already sees but to make visible what not everybody sees.

—Josef Pieper, Only the Lover Sings, “Three Talks in a Sculptor’s Studio: Vita Contemplativa”

Writing during a period of intense political upheaval in twentieth-century Europe, Josef Pieper spent his entire life reflecting on the value of culture in modern society and the necessity of the creative arts for the nourishment of the human soul. Moreover, he intuitively understood that artistic vision, be it visual, musical or literary, is a conduit for the contemplative life. By fine-tuning our capacity to observe manifest phenomena, we may turn our attention simultaneously upwards and inwards, wherein we may witness a vast ocean of beingness, love and benevolence, indeed the very Beatific Vision itself.

If we now look from this perspective at the artistic work before us, we clearly see an art that it neither-nor: neither is it ‘abstract’, much less ‘absolute art’, which is indifferent to the forms of the visible world; nor can we speak of a blunt and merely descriptive realism. These two somewhat involuted opposites need an explanation; after all, what do we mean by ‘neither realism nor abstraction’?

To this end we have to consider a certain aspect of the term ‘contemplation’, so far not yet mentioned. For even the most intensive seeing and beholding may not yet be true contemplation. Rather, the ancient expression of the mystics applies here: ubi amor, ibi oculus—the eyes see better when guided by love; a new dimension of ‘seeing’ is opened up by love alone! And this means contemplation is visual perception prompted by loving acceptance!

—Josef Pieper, Only the Lover Sings, “Three Talks in a Sculptor’s Studio: Vita Contemplativa“

Post Notes

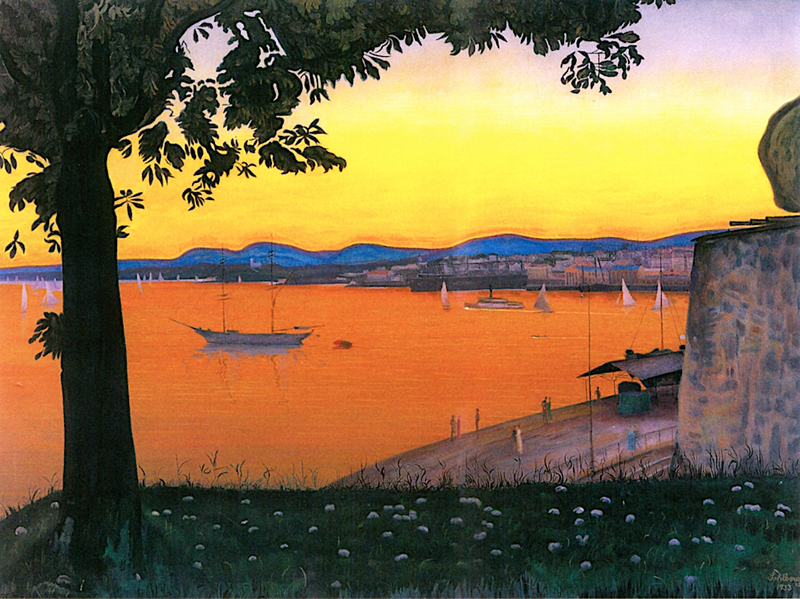

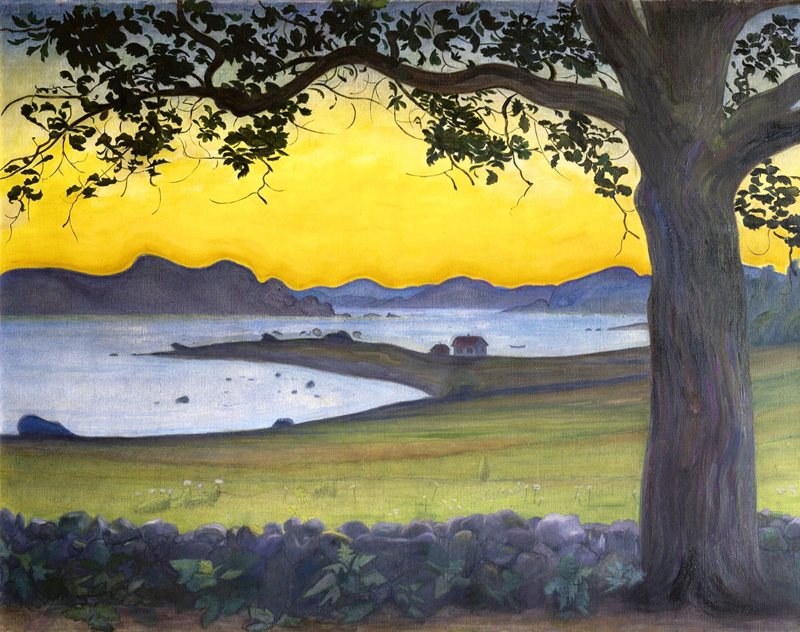

- Feature image: Harald Oskar Sohlberg, Andante, Public Domain

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Plato: Phaedrus and the Charioteer

- Michel de Montaigne: On Solitude

- Rousseau: Meditations of a Solitary Walker

- Leo Tolstoy: A Confession

- Guy Laramée: Fraîcheur

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme