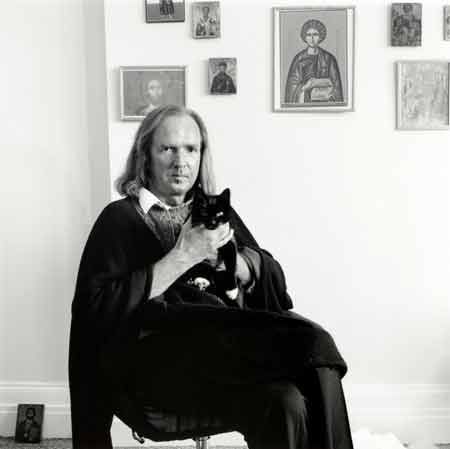

Photograph: © George Newson/Lebrecht Music & Arts

The soundlessness of sound

“We seem to have lost our contact with the primordial: the idea of—call it divine revelation as opposed to something that’s learned by the human intellect—something that, if you lay yourself completely open, and you just open your heart completely, something will actually come into it.”

—John Tavener

WHY DO WE yearn to express the inexpressible? It is indeed paradoxical that the human soul longs for silence and yet similarly feels compelled to translate that experience into word, painting or music. Perhaps it is only through juxtaposition that the pristine exquisiteness of stillness can be so profoundly conveyed in contrast to the tinnitus of everyday life.

Moreover, imbibing art created in the crucible of everlasting silence has the power to awaken within us a recognition of our inner selves and the space for sacred revelation, the puissance of sound probably being the most intoxicating and alluring of all the cultural arts.

British composer, Sir John Tavener (28th January 1944–12th November 2013), was a deeply spiritual man, having converted to the Russian Orthodox Church in his thirties. Describing his own music as “icons in sound”, he drew from many religious traditions, including Christianity, Islam and Hinduism, to produce some of the most sublime and ethereal compositions I have ever heard: The Whale; The Protecting Veil; Song for Athene; and The Lamb, which was inspired by William Blake and featured in Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty.

John Tavener, Towards Silence

John Tavener is often grouped with other contemporary classical composers, collectively called “Holy Minimalists”, including Henryk Górecki and Arvo Pärt, though each exhibits his own unique musicality in relation to articulating the divine. Indeed, Tavener once commented that there are plenty of artists who can show the way to hell—he wanted his music instead to lead us unto paradise.

Towards Silence was inspired by John Tavener’s reading of Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta by René Guénon, a seminal work on Hindu mythology and metaphysics and which had a profound impact on the composer: “From an exoteric sense, the work may be seen as a meditation on the different states of dying but from an esoteric sense, it is a meditation on the four states of Atma.”

The piece is written for four string quartets and a large Tibetan bowl in four movements. Tavener’s vision was for all four quartets to be positioned high up in the cathedral dome, invisible to the audience, and arranged in the shape of a cross, bringing all the great mystical traditions together in one orchestration of unifying reverberation.

‘Vaishvanara’: the Waking State, which has knowledge of external objects, and which has nineteen mouths, and is the world of gross manifestation. (Mandukya Upanishad 1-3)

‘Taijasa’: the Dream State, which has knowledge of inward objects, which has nineteen mouths, and whose domain is the world of subtle manifestation. (Mandukya Upanishad 1-4)

‘Prājña’: the Condition of Deep Sleep. When the being who is asleep experiences no desire and is not the subject of any dream, he has become Atma, and is filled with Beatitude (Ananda).

‘Turiya’: That which is Beyond. The greatest State is the fourth, totally free from any mode of existence whatever, with fullness of Peace and Beatitude without duality.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, Tavener, who had Marfan Syndrome, an inherited condition that attacks the body’s connective tissue, had a series of heart attacks before the piece was performed and thus Towards Silence took on a profound significance in the composer’s life.

Fellow composer, John Rutter, once said that John Tavener had the “very rare gift” of being able to “bring an audience to a deep silence”; indeed, when art is harnessed as a means to expressing the inexpressible, it has the power and potency to reconnect us with all that lies beyond manifested phenomena and the nondual state of perfected peace.

Musically, I have tried to express these States of Atma by using four string quartets sounding unseen from high galleries, with a large Tibetan temple bowl sounding every nineteen beats (symbolizing the nineteen mouths) in the first three States and then pulsing ‘eternally’ in the last, unconditioned State.

I have used five revolving ideas which start in the first State as the shortest, the most complex and the most manifest. In the second ‘Dream State’, the length is increased mathematically and is twice the length of the first State, as the sound is less complex and less manifest.

The third State (Deep Sleep) is a kind of ‘halo’ of still sound, and is mathematically three times the length of the first State. The final State is the longest, the quietest and the most full statement of the five revolving ideas, and it is played muted, at the very threshold of audibility, which finally leads to silence.

In a sense this is not music that should be heard as concert music but rather meditated on as a form of ‘liquid’ metaphysics. I offer this musical experiment as a poor man’s mite and dedicate it to the memory of that great man, René Guénon, who died virtually unknown in Cairo in 1951 and who brought my attention to the Vedanta.