The way, the truth and the life

I am—yet what I am none cares or knows;

My friends forsake me like a memory lost:

I am the self-consumer of my woes—

They rise and vanish in oblivious host,

Like shadows in love’s frenzied stifled throes

And yet I am, and live—like vapours tossedInto the nothingness of scorn and noise,

Into the living sea of waking dreams,

Where there is neither sense of life or joys,

But the vast shipwreck of my life’s esteems;

Even the dearest that I loved the best

Are strange—nay, rather, stranger than the rest.I long for scenes where man hath never trod

A place where woman never smiled or wept

There to abide with my Creator, God,

And sleep as I in childhood sweetly slept,

Untroubling and untroubled where I lie

The grass below—above the vaulted sky.

OF ALL THE poetry I have read over the years, I forever return to John Clare’s haunting composition, despite its outwardly bleak interpretation, in order to realign myself with the world. There is such a profound simplicity about it, with every single word perfectly chosen for its meaning, sound and cadence that it is, in my opinion, the most exquisitely formed, sagacious piece of versification I have ever read.

Indeed, it aroused me at university whilst reading a degree in English literature to explore more deeply the work of the Romantic poets; it then motivated me to write a book about teachers of non-duality and a quest for the meaning of things; and now it still captivates me whenever life continues to baffle and bewilder and I yearn for calmer seas. In a (mis)attributed quote by C. S. Lewis in the film, Shadowlands, written by William Nicholson, the novelist remarks, “We read to know we’re not alone.”

“I Am” is a powerful, direct expression of the abject disintegration of self and the yearning for absolute communion with the divine. Imbued with the utter sorrow and alienation at the horror of living, the narrator’s outcast state is left marooned on a solitary shore to consolidate his loss and contemplate his position in the cosmos. Only the hope of spiritual redemption can offer any form of salvation and peace.

More specifically, I would suggest, the poem alludes to the celebrated tautology of Exodus 3:14, “I am that I am”. But whereas the Biblical scribe’s proclamation is one of liberation and immortality, Clare’s poetic de profundis by contrast is, on the face of it, one of impotence, helplessness and despair.

What is interesting to note about this poem is that it was composed by John Clare (13th July 1793–20th May 1864) in Northampton General Lunatic Asylum, whilst he was certified for mental illness. Indeed, he would spend most of his entire adult life in and out of psychiatric institutions, owing to bouts of depression, hallucinations and madness, even believing himself at one point to be Lord Byron and William Shakespeare.

Nonetheless, he was not the only poet to compose a work of genius in the aftermath of psychological trauma; T. S. Eliot’s Modernist masterpiece, The Waste Land, was similarly created during recovery from a nervous breakdown and the artist and visionary, William Blake, is believed by many to have been completely raving mad.

Thus in spite of, or even because of, his descent into mania, Clare is able to penetrate and grasp the very deepest meaning of things, that life is essentially a “waking dream”, a “nothingness of scorn and noise”, littered with the “vast shipwreck of … life’s esteems”.

Deliverance from the detritus of daily existence, Clare believes, lies only within a state of dreamless slumber and childhood innocence, devoid of the vicissitudes of his former companions, and where self is no more.

And yet this is far from a nihilistic vision of nonexistence; it is terrain only too familiar for fellow Romantic artists and mystics where being and nonbeing are inextricably intertwined into an all-pervading witnessing presence, encompassing the “grass below” and “above the vaulted sky”.

It is a place for which Clare deeply longs and has indeed already known during “delusional” episodes of his unconscious mind; a place where, no longer even caring what he actually is, he may abide in peaceful holy communion with the Creator, the primordial consciousness, the “I am that I am”.

Post Notes

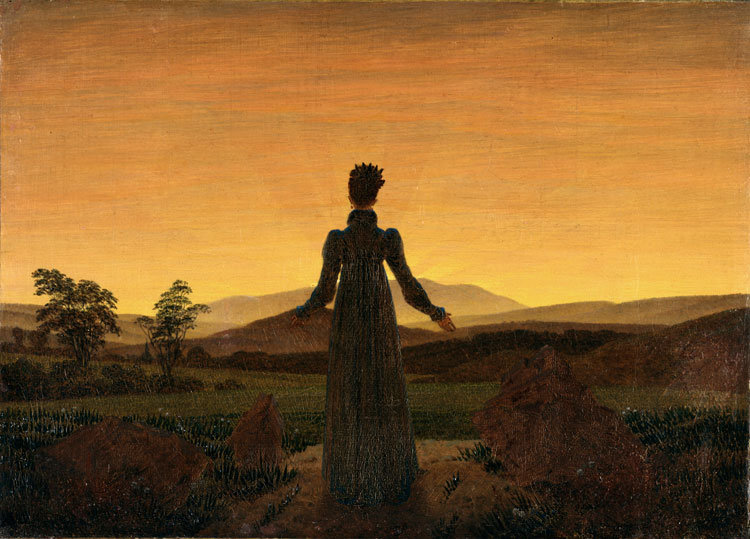

- Feature image: Caspar David Friedrich, The Monk by the Sea, Public Domain

- John Clare Cottage

- Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Cloud

- T. S. Eliot: A Man Out of Time

- Andrew Marvell: On a Drop of Dew

- Roger Housden: Ten Poems for Difficult Times

- Liam Ó Muirthile: Camino de Santiago, Dánta, Poems, Poemas

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Wallace Stevens: Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme