Image: Public Domain

The joys of the reclusive life

“The task I had set myself could only be performed in absolute isolation;

it called for long and tranquil meditations,

which are impossible in the bustle of society life.”

ONCE IN A WHILE, one comes across a literary gem of such beauty and refinement, it almost takes one’s breath away. Les rêveries du promeneur solitaire (Meditations of a Solitary Walker), an unfinished manuscript composed sometime between 1776 and 1778, is one of the last works of literature that Jean-Jacques Rousseau ever wrote.

Originally divided into Ten Walks, my particular Penguin pocketbook contains the First, Third, Fifth and Eighth Walks, which focus on his time spent on the Island of Saint Pierre, in the middle of Lake Bienne, Switzerland.

Reaching the forties milestone, Genevan thinker Rousseau (28th June 1712–2nd July 1778), one of the great European philosophes, is having the proverbial midlife crisis and is taking stock by assessing the life he has lived so far:

Since the days of my youth I had fixed on the age of 40 as the end of my efforts to succeed, the final term of my various ambitions. I had the firm intention, when I reached this age, of making no further effort to climb out of whatever situation I was in and of spending the rest of my life living from day to day with no thought for the future.

When the time came I carried out my plan without difficulty, and although my fortune at that time seemed to be on the point of changing permanently for the better, it was not only without regret but with real pleasure that I gave up these prospects.

In shaking off all these lures and vain hopes, I abandoned myself entirely to the nonchalant tranquillity which has always been my dominant taste and more lasting inclination. I quitted the world and its vanities, I gave up all finery—no more sword, no more watch, no more white stockings, gilt trimmings and powder, but a simple wig and a good solid coat of broad cloth—and what is more than all the rest, I uprooted from my heart the greed and covetousness which gave value to all I was leaving behind.

I did not confine my reformation to outward things. Indeed I became aware that this change called for a revision of my opinions, which although undoubtedly more painful was also more necessary, and resolving to get it all over at once, I set about a strict self-examination which was to order my inner life for the rest of my days as I would wish it to be at the time of my death.

—Third Walk

Image: Public Domain

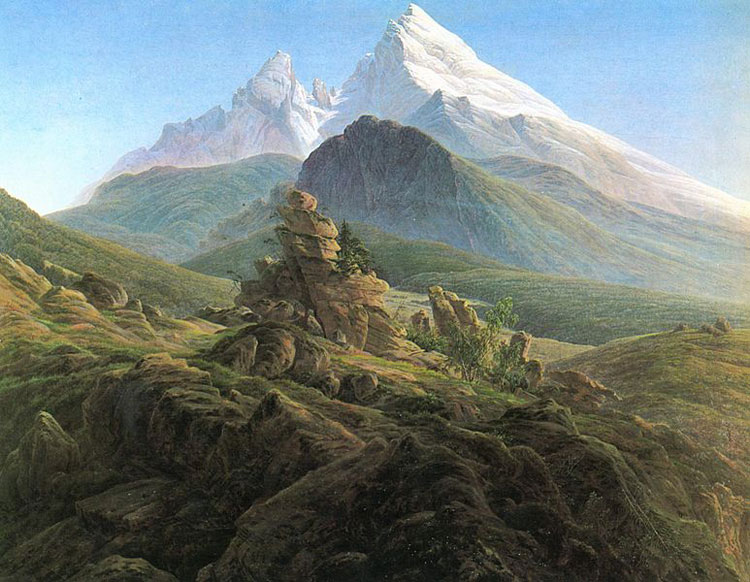

Renunciation of the world leads to peace

Rousseau laments the scorn and criticism that has been lavished upon him, which has led him to seek refuge far away from the vagaries of civilization and return, as far as is possible at least, to life harking back to the “noble savage”, the idealized conceptual state of uncivilized man, symbolizing innate goodness, uncorrupted by the ways of the world.

Why he suffers such acute opprobrium is not made clear in this particular text, though one can only assume it is owing to his philosophical stance against the principles of Enlightenment thinking and its belief in the sovereignty of the power of the mind.

Indeed, Rousseau’s ideas were precursors to the Age of Sensibility and Romanticism, whereby subjectivity, feeling and introspection took centre stage in a person’s life:

It is from this time that I can date my total renunciation of the world and the great love of solitude which has never since left me. The task I had set myself could only be performed in absolute isolation; it called for long and tranquil meditations, which are impossible in the bustle of society life.

So I was obliged to adopt for a time another way of life, which I subsequently found so much to my taste that since then, I have only interrupted it for brief periods and against my will, returning to it most gladly and following it without effort as soon as I was able; and when men later reduced me to a life of solitude, I found that isolating me to make me miserable, they had done more for my happiness that I had been able to do myself.

—Third Walk

Image: Public Domain

In terms of inner faith, Rousseau strongly rejected all forms of institutionalized religion, believing that God was not something to be intellectualized through catechisms and dogma; rather, to be celebrated through feelings of reverence and awe. Communing with nature, in particular, he believed enhanced such emotion:

But if there is a state where the soul can find a resting-place secure enough to establish itself and concentrate its entire being there, with no need to remember the past or reach into the future, where time is nothing to it, where the present runs on indifferently but this duration goes unnoticed, with no sign of the passing of time, and no other feeling of deprivation or enjoyment, pleasure or pain, desire or fear than the simple feeling of existence, a feeling that fills our soul entirely, as long as this state lasts, we can call ourselves happy, not with a poor, incomplete and relative happiness such as we find in the pleasures of life, but with a sufficient, complete and perfect happiness which leaves no emptiness to be filled in the soul.

Such is the state, which I often experienced on the Island of Saint Pierre in my solitary reveries, whether I lay in a boat and drifted where the water carried me, or sat by the shores of the stormy lake, or elsewhere, on the banks of a lovely river or a stream murmuring over the stones.

—Fifth Walk

Ego versus self-esteem

Rousseau was one of the first philosophers to make the clear distinction between amour de soi, love of self or innate self-esteem, and amour-propre, self-love or egotistical pride.

Having reached a state of contentment, he remarks in his Eighth Walk: “… alone with myself, contented with myself and already enjoying the happiness, which I feel I have deserved … Love of self alone is active in all of this, self-love has no part.”

Image: Public Domain

Similar in sensibility to Thoreau’s Walden, Montaigne’s On Solitude and Emerson’s “Waldeinsamkeit”, Meditations of a Solitary Walker is a manifesto for anyone wanting to distance themselves from the hubbub of society by finding detachment in being utterly on their own:

Everything is finished for me on this earth. Neither good nor evil can be done to me by any man. I have nothing left in the world to fear or hope for, and this leaves me in peace at the bottom of the abyss, a poor unfortunate mortal, but as unmoved as God himself.

—First Walk

Post Notes

- Michel de Montaigne: On Solitude

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Cloud

- Seneca: On Tranquillity of Mind

- Leo Tolstoy: A Confession

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Waldeinsamkeit

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Rainer Maria Rilke: On Solitude

- John Zerzan: Silence