Jean Cocteau, Orpheus

Capturing the soul of the artist on celluloid

A film is not the telling of a dream but a dream in which we all participate together through a kind of hypnosis and the slightest breakdown in the mechanics of the dream wakens the dreamer, who loses interest in a sleep that is no longer his own.

By dream, I mean a succession of real events that follow on from one another with the magnificent absurdity of dreams, since the spectators would not have linked them together in the same way or have imagined them for themselves but experienced them in their seats as they might experience in their beds, strange adventures for which they are not responsible …

—Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema

WATCHING THE FILMS of the French auteur, Jean Cocteau (5th July 1889–11th October 1963) transports one back to a time when motion pictures were full of a myriad of artistic possibilities that are rarely explored in contemporary cinema.

Forever the polymath, Cocteau championed an elegant and ethereal aesthetic through his creative engagement not only through filmmaking and the moving image but also theatre, painting and literature. Indeed, he often referred to his work as “poetry”—not that which relates to verse but rather a sublime, lyrical sensibility rooted in intellectual integrity and hard work.

Drawing on the spirit of the Romantics, he thus classified his films as Poésie de Cinéma, his novels as Poésie de Roman and his essays Poésie Critique in his quest to “… illuminate various facets of the themes that obsess me: the loneliness of individuals, waking dreams and childhood, that dreadful state of childhood from which I shall never escape.”

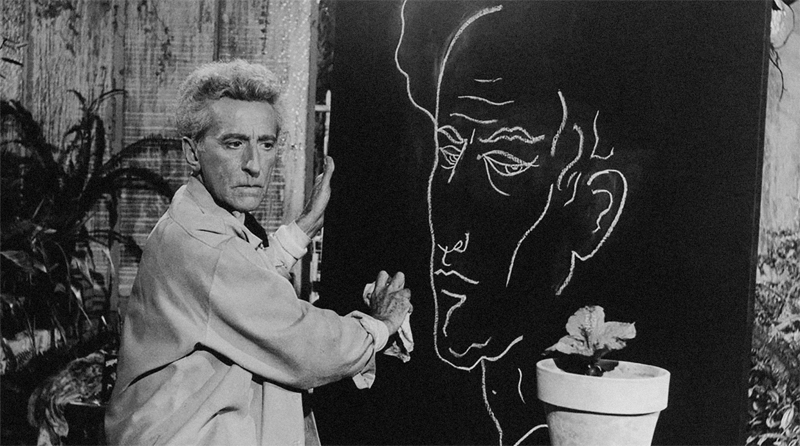

Image: © Edgardo Cozarinsky

The Poetic Muse

Jean Cocteau drew inspiration from the avant-garde circles in which he mingled during the pre-war Paris era, which included the likes of Kenneth Anger, Pablo Picasso, Jean Hugo, Henri Bernstein, Marlene Dietrich, Coco Chanel, Erik Satie, Igor Stravinsky, Colette, Édith Piaf and his long-term lover and collaborator, Jean Marais.

Known for many artistic accomplishments—the novel Les Enfants Terribles, and the films Les Parents Terribles and La Belle et La Bête—it is his Orphic trilogy that is considered to be his masterwork, comprising Le Sang d’un Poète (1930), Orphée (1949) and Le Testament d’Orphée (1960), in which he utilizes the legendary Greek myth of Orpheus to explore the relationship between art and life, imagination and reality, illusion and truth.

Nobody can believe in a famous poet whose name has been invented by a writer. I had to find a mythical bard, the bard of bards, the Bard of Thrace. And his story is so enchanting that it would be crazy to look for another. It provides the background on which I embroider. I do nothing more than to follow the cadence of all fables which are modified in the long run according to who tells the story.

—Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema

Le Sang d’un Poète

Through a stunning montage of mood and monochrome, Cocteau’s trilogy exudes an oneiric, timeless beauty rarely seen before, or since, in his evocation of the Poetic Muse. The first instalment, Le Sang d’un Poète (The Blood of a Poet), examines the inner struggle of the artist and the correlation between dreams and art, life and the extinction of self.

Exquisitely acted by Enrique Riveros, the poet must go through a series of metaphorical deaths in order to be reborn in a state that is closer to his true being. As Cocteau himself remarked, “Poets … shed not only the red blood of their hearts but the white blood of their souls.”

I am rather surprised whenever I hear people chatter on about poetry in cinematography, the fantastic in cinematography and, particularly, escapism, a fashionable term which implies that the audience is trying to get out of itself, while in fact beauty in all its forms drives us back into ourselves and obliges us to find in our own souls the deep enrichment that frivolous people are determined to seek elsewhere.

—Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema

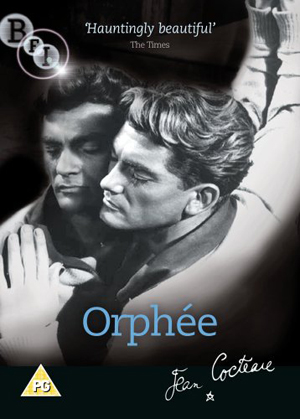

Orphée

Despite a hiatus of nearly twenty years, the next instalment, Orphée (Orpheus) continues the mythic and supernatural theme in a triumph of poetic storytelling. A famous poet (played by Jean Marais, of whom Cocteau remarked, “[He] illuminates the film for me with his soul”), who is shunned by his Left Bank contemporaries, struggles with divided love for his wife, Eurydice (played by Marie Déa), and a mysterious princess (played by Maria Casarès).

When Eurydice is killed, Orpheus follows the princess through Cocteau’s iconic mirrored portal into the underworld, in order to reclaim his wife who is carrying his child. The condition of her revival and release is that Orpheus may never look upon her again, a stipulation he is unable to keep.

Speaking of the prevailing themes of the film, Cocteau wrote:

1. The successive deaths through which a poet must pass before he becomes, in that admirable line from Mallarmé, tel qu’en lui-même enfin l’éternité le change—changed into himself at last by eternity.

2. The theme of immortality: the person who represents Orphée’s Death sacrifices herself and abolishes herself to make the poet immortal.

3. Mirrors: we watch ourselves grow old in mirrors. They bring us closer to death.

—Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema

Image: © Jean Cocteau

Le Testament d’Orphée

In the final part of the trilogy, Jean Cocteau himself portrays an 18th-century poet who travels through space-time in search of divine knowledge. Lost in a mystical wilderness, he encounters ghosts and goddesses from the past who precipitate his death and eventual resurrection.

With an eclectic ensemble that included Pablo Picasso, Yul Brynner and Jean Marais, this final instalment concludes Cocteau’s Orphic journey into an examination of the torturous relationship between the artist and his work.

In Le Testament d’Orphée, events follow one another as they do in sleep, when our habits no longer control the forces within us or the logic of the unconscious, foreign to reason. A dream is strictly mad, strictly absurd, strictly magnificent and strictly atrocious. But no part of us ever judges it. We submit to it, without activating the abominable human tribunal that accords itself the right to condemn and absolve.

—Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema

Jean Cocteau’s legacy

The postmodernist world which we now inhabit often scoffs at an artist’s attempts to evoke Romantic sensibilities and poetic beauty for their own sake, preferring instead to exult the ironic, sarcastic and profane.

And yet for those of us who yearn for a more sacred expression that embodies ethereal and experimental grandeur, the artistic oeuvre of Jean Cocteau is a sumptuous dream from which I never wish to be awakened.

When I make a film, it is a sleep in which I am dreaming. Only the people and places of the dream matter. I have difficulty making contact with others, as one does when half-asleep. If a person is asleep and someone else comes into the sleeper’s room, this other person does not exist. He or she exists only if introduced into the events of the dream …

—Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema

Post Notes

- Musée Jean Cocteau

- Jean Cocteau: Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer

- Alain Resnais: Last Year in Marienbad

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Abbas Kiarostami: 24 Frames

- Kaneto Shindo: The Naked Island

- Maya Deren: A Study in Choreography for Camera

- David Lynch: Catching the Big Fish