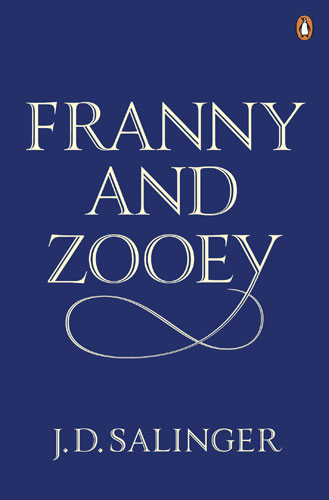

Typeface: Seb Lester

Redemptive love

“I’m sick of not having the courage

to be an absolute nobody.”

JUST BEFORE THE death of Jerome David “J. D.” Salinger in 2010, his publisher at Hamish Hamilton (an imprint of Penguin) sat down with the cult author to discuss the new jacket artwork for the forthcoming reissues of his work.

Salinger was single-minded about how he wanted his texts to be printed: no author photograph; no biography; no cover blurb; no endorsements; no quotes; no nothing, except of course the title and his name.

Hamish Hamilton decided, therefore, to honour his books with a brand new typeface, giving them at least some kind of distinction, and commissioned the celebrated type designer, Seb Lester, the job of illuminating Salinger’s front covers.

The results are entirely befitting in their sophistication and minimalism; the typographical nuances embodying everything that Salinger stood for in his prose and what he ultimately became in person—iconoclast; literary paragon; recluse.

Eastern religion

J. D. Salinger (1st January 1919–27th January 2010) had been drafted into the army during World War II, where he saw active military service in Europe, culminating in a billet to a concentration camp shortly after it was liberated by the Allies. Inevitably, the horror of war took its toll and Salinger was hospitalized for “combat stress reaction” when Germany was defeated.

Back in the States, traumatized and disillusioned, Salinger sought solace in Eastern religion, and in particular, the teachings of Zen Buddhism, Advaita Vedanta and Russian folklore. His literary offerings, therefore, became the perfect outlet for his growing dissatisfaction at the meaninglessness of the world and all its affectations, with the hope of redemption that only philosophy and religion could bring.

After publishing his masterwork, The Catcher in the Rye, in 1951—the story of a disaffected youth personified by the iconic Holden Caulfield—Salinger turned his attention to composing short stories about a family he created called the Glasses: the parents, two former vaudeville entertainers, Les and Bessie; and their seven precocious children, Seymour, Buddy, Boo Boo, Walter, Waker, Zooey and Franny. The children are all hopelessly intelligent and have appeared on the radio talk show, It’s A Wise Child.

The short story, Franny, and the novella, Zooey, were printed separately in The New Yorker magazine in 1955 and 1957 respectively, until they were both published together in book form a few years later in 1961, becoming an instant bestseller.

Franny

Franny Glass is a 20-year-old English major college student, and youngest of the Glass family, who goes to meet her boyfriend, Lane Coutell, also an English major, for a weekend football game at his college.

As with any well-crafted short story, we are immediately shown the nucleus of Salinger’s philosophy—their rendezvous perfectly encapsulates his sympathies for the innocence and straightforwardness of youth, struggling to make sense of a world contaminated by self-aggrandisement, conformity and control.

Irritated by Lane’s pontificating over his own academic achievements, Franny bemoans the inauthenticity of college life and the egotism of the teachers in the faculty:

‘I’m just sick of ego, ego, ego. My own and everybody else’s. I’m sick of everybody that wants to get somewhere, do something distinguished and all, be somebody interesting. It’s disgusting.’

In a further protracted rant, she informs Lane that she has also quit her part in a college theatre production, in a stand against the phoniness of the acting world:

‘It started embarrassing me. I began to feel like such a nasty little egomaniac … I don’t know. It seemed like such poor taste, sort of, to want to act in the first place. I mean all the ego. And I used to hate myself so, when I was in a play, to be backstage after the play was over. All those egos running around feeling terribly charitable and warm. Kissing everybody and wearing their makeup all over the place, and then trying to be horribly natural and friendly when your friends came backstage to see you. I just hated myself …’

In fact, she is utterly disgusted by everyone in hers and Lane’s social orbit, decrying that all of humanity is obsessed with personal advancement and the perpetuation of self-image.

Moreover, as her existential crisis crescendoes and starting to feel physically unwell, she reluctantly starts telling Lane about the pea-green book she has borrowed from the college library and is keeping concealed in her handbag.

The Way of a Pilgrim

Given that he was writing in the tailwind of the Beat Generation and their preoccupation with Oriental philosophy, it is interesting to see that Salinger chose to illustrate the story’s major motif with a text more associated with Eastern Christianity, rather than a Buddhist sutra or an Indian Upanishad.

Written by a nineteenth-century Russian peasant, The Way of a Pilgrim recounts the narrator’s journey as a mendicant traveller across Russia while practising the “Jesus Prayer” by repeating the words, “Lord Jesus Christ have mercy on me”, which he recites uninterruptedly, as a type of mantra:

‘… the starets [an elder of a Russian Orthodox monastery] tells the pilgrim that if you keep saying that prayer over and over again—you only have to just do it with your lips at first—then eventually what happens, the prayer becomes self-active …

‘Something happens after a while. I don’t know what, but something happens, and the words get synchronized with the person’s heartbeats, and then you’re actually praying without ceasing. Which has a really tremendous, mystical effect on your whole outlook. I mean that’s the whole point of it, more or less. I mean you do it to purify your whole outlook and get an absolutely new conception of what everything’s about.’

Franny feels an immediate affinity with the Jesus Prayer and believes that by repeating it, she may purge herself of all hypocrisy and the need to conform to societal conditioning, rendering her mind still and her heart pure, with a vision of a higher power:

‘You get to see God. Something happens in some absolutely nonphysical part of the heart—where the Hindus say that Atman resides, if you ever took any Religion—and you see God, that’s all.’

Overwhelmed with nausea and perspiration, and no doubt feeling vulnerable after her “confession”, Franny finally excuses herself from the table and faints on the way to the bathroom:

Alone, Franny lay quite still, looking up at the ceiling. Her lips began to move, forming soundless words, and they continued to move.

And thus the story ends on a spiritual cliffhanger, with the Jesus Prayer resounding in Franny’s heart.

Zooey

The tale of Zooey picks up the story the following week and is narrated by Buddy Glass. Franny is in a state of complete listlessness and mental exhaustion; her mother, Bessie, persuades her son, Zooey, to talk to her daughter in an attempt to alleviate her spiritual crisis.

Zooey tries to console his sister; however, she becomes deeply upset and repeats her feelings of disgust for college education:

‘What happened was, I got the idea in my head—and I could not get it out—that college was just one more dopey, inane place in the world dedicated to piling up treasure on earth and everything. I mean treasure is treasure, for heaven’s sake. What’s the difference whether the treasure is money, or property, or even culture, or even just plain knowledge? […] Sometimes I think that knowledge—when it’s knowledge for knowledge’s sake, anyway—is the worst of all. […]

‘I don’t think it would have all got me quite so down if just once in a while—just once in a while—there was at least some polite little perfunctory implication that knowledge should lead to wisdom, and that if it doesn’t, it’s just a disgusting waste of time! But there never is! You never even hear any hints dropped on a campus that wisdom is supposed to be the goal of knowledge. You hardly ever even hear the word “wisdom” mentioned!’

Zooey then challenges Franny on her motives for reciting the “Jesus Prayer”, prompting her to become furious with rage:

‘All right, take it easy, take it easy.’

‘I can’t take it easy! You make me so mad! What do you think I’m doing here in this crazy room—losing weight like mad, worrying Bessie and Les absolutely silly, upsetting the house, and everything? Don’t you think I have sense enough to worry about my motives for saying the prayer? That’s exactly what’s bothering me so. Just because I’m choosy about what I want—in this case, enlightenment, or peace, instead of money or prestige or fame or any of those things—doesn’t mean I’m not as egotistical and self-seeking as everybody else. If anything, I’m more so! I don’t need the famous Zachary Glass to tell me that!’

Zooey cares passionately for his younger sister so decides to take a different approach by calling her on the telephone, whilst pretending to be Buddy, their revered, spiritually-wise, older brother. She takes the call in Buddy’s former bedroom, though she quickly sees through the ruse. Whilst she drags on a cigarette, Zooey tries again to appease her existential malaise:

‘You can say the Jesus Prayer from now till doomsday, but if you don’t realize that the only thing that counts in the religious life is detachment, I don’t see how you’ll ever even move an inch. Detachment … and only detachment. Desirelessness. “Cessation from all hankerings.”’

Zooey, it would appear for now, has done his job and Franny’s crisis is, temporarily at least, resolved. You also feel that Salinger has got a great deal off his chest about his attitudes to Western consumerist culture, and how the only way out of spiritual angst is by executing a total disinterestedness to life.

Indeed, Franny and Zooey, itself composed in a manner not unlike a Zen koan, is a perfectly formed distillation of seemingly inconsequential moments, infused with profound and illuminating truths. It is no coincidence that their family name is Glass.

And thus so it is, through Salinger’s dazzling use of domestic drama, that Franny is led, with the aid of her brother’s love, from a state of ignorance to wisdom, from suffering to peace, leaving the Jesus Prayer resounding deeply in her very soul:

Franny took in her breath slightly but continued to hold the phone to her ear. A dial tone, of course, followed the formal break in the connection. She appeared to find it extraordinarily beautiful to listen to, rather as if it were the best possible substitute for the primordial silence itself.

But she seemed to know, too, when to stop listening to it, as if all of what little or much wisdom there is in the world were suddenly hers. When she had replaced the phone, she seemed to know just what to do next, too. She cleared away the smoking things, then drew back the cotton bedspread from the bed she had been sitting on, took off her slippers, and got into the bed. For some minutes, before she fell into a deep, dreamless sleep, she just lay quiet, smiling at the ceiling.

Post Notes

- Salinger.org website

- Seb Lester’s website

- Leo Tolstoy: The Death of Ivan Ilyich

- Leo Tolstoy: The Three Hermits

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Hermann Hesse: The Journey to the East

- W. Somerset Maugham: The Saint

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- E. M. Forster: The Celestial Omnibus