Photograph: © Pyramide Films

The journey home

“Reda: Why didn’t you fly to Mecca? It’s a lot simpler.

The Father: When the waters of the ocean rise to the heavens, they lose their bitterness to become pure again …

Reda: What?

The Father: The ocean waters evaporate as they rise to the clouds. And as they evaporate they become fresh. That’s why it’s better to go on your pilgrimage on foot than on horseback, better on horseback than by car, better by car than by boat, better by boat than by plane.”

LE GRAND VOYAGE by French-Moroccan auteur, Ismaël Ferroukhi (born 1962), is one of those rare cinematic events that leaves you weeping long after the final closing moments, when you realize that what you have just experienced is your own inner pilgrimage into the deepest chambers of your heart in humble homage to the puissance of human relationships, the potency of spiritual journeys and, above all, the power of eternal love.

Photograph: © Pyramide Films

The first ever fiction feature to be granted permission to film in Mecca, Le Grand Voyage explores the relationship between a devout Muslim immigrant Moroccan father (Mohamed Majd) and his secular French adolescent son, Réda (Nicolas Cazalé), as they set off en route from Provence, France, in a beat-up blue Peugeot to make the annual hajj or pilgrimage, travelling through Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Syria and Jordan before finally reaching Mount Arafat in Saudi Arabia, where the Prophet Muhammad delivered his final sermon more than 1,400 years ago.

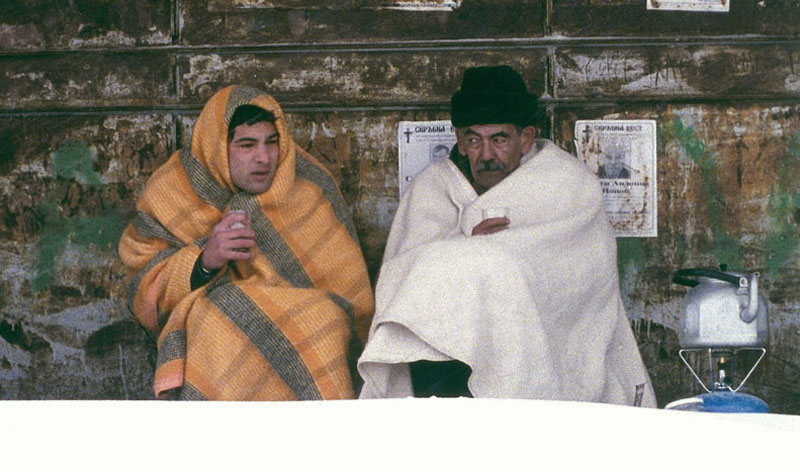

Forced to leave behind his girlfriend, Lisa, and abandon his impending Baccalauréat exams, Réda is seething with anger and annoyance at his autocratic father, who similarly feels frustrated by his son’s wayward view of life, their emotional distance and dissonance aptly displayed by the father always speaking in Maghrebi Arabic and the son always responding in Provençal French, despite the fact that both understand each other’s mother tongue.

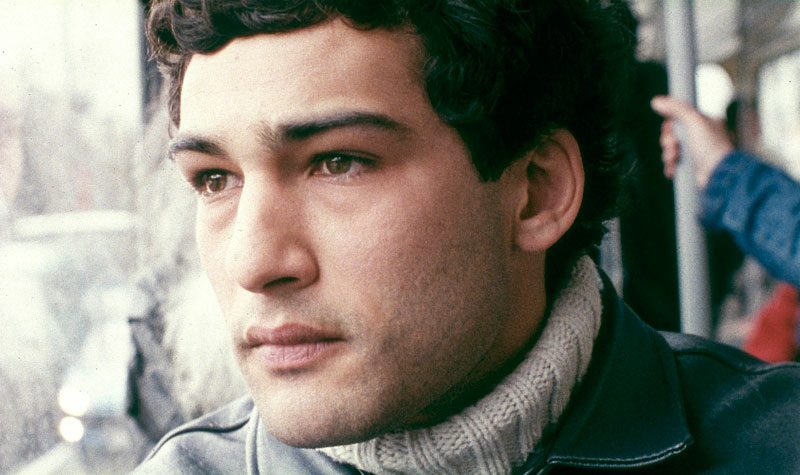

Le Grand Voyage is not, however, an examination of the dichotomies of the spoken word; indeed, very little is actually said between the men as they forge their way through passport controls, bustling city streets and empty autoroutes that stretch for mile upon mile upon mile into the never-ending distance. Rather, it is the somatic exploration of all that is unsaid, expressed so compellingly through the nuanced facial gestures and subtle physical postures of the two principal protagonists.

Photograph: © Pyramide Films

Moreover, the film becomes replete with meaningful symbolism, pointing towards elements and archetypes deep within the psyche, that only sequences with minimal dialogue are able to reveal: a silent old woman in a black burqa slipping onto the back seat and accompanying the men for many hours at the start of their trip representing, according to the director, the shadow side of human nature; the orange passenger door of the blue Peugot automobile emblematic of the father’s passionate Muslim faith in contradistinction to his son’s cool agnosticism and ennui; Réda often arousing from sleep and rubbing his eyes, metaphorical of the various states of human consciousness through which he must pass until his final awakening and rebirth.

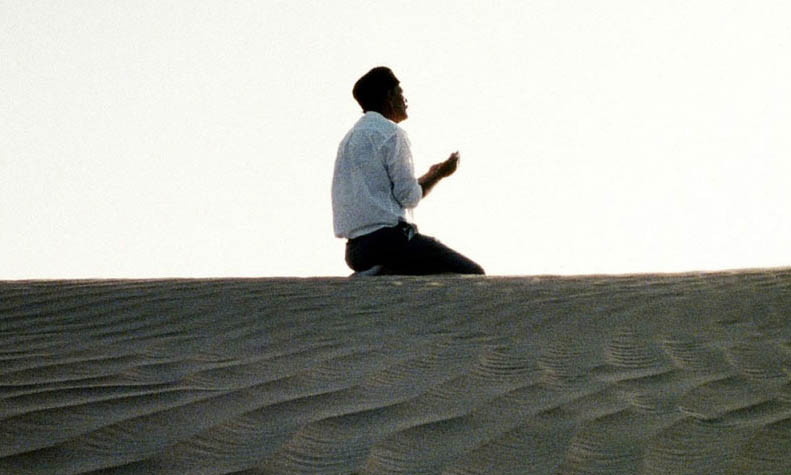

One of my favourite scenes is a dream sequence in the Syrian desert, in which Réda sees his father dressed as a goatherd, shepherding his flock over the dunes. Réda calls out to him but is ignored and then, to his horror, is pulled deep down into the sand. As he flails about in utter panic, he abruptly wakes up to see his father kneeling in prayer, his palms in supplication to Allah. The portentous significance is understood when we see another herd of goats being driven through the streets of Mecca under the moonlight when their journey has come to an end.

Indeed, Le Grand Voyage is a love letter to all that lies beneath the surface of things—feeling and emotion, faith and silence, the very unifying substratum of life itself and what it means to be human, all set against a passing backdrop of stunning European and Middle-Eastern scenery: snowy mountains and sapphire skies, shimmering deserts and setting suns.

Photograph: © Pyramide Films

Upon reaching Saudi Arabia, in a deeply poignant moment, Réda and his father sit side by side leaning against the car and express how much they have learnt from their communal journey. They also meet fellow hajjis, sharing food and stories of their trips. Despite the fact that Réda’s heart is opening up to his father’s religion, whilst the pilgrims pray on their prayer mats, we feel deeply moved by his divided loyalties as he writes his girlfriend’s name, Lisa, in the sand with his shoes.

At last, Mecca is in their sights. The call of the muezzin hypnotizes us into a heightened anticipation and thrill of the unknown. The father prepares himself for Ihram [a sacred state which a Muslim must enter in order to perform the hajj by performing cleansing rituals and wearing prescribed attire] and leaves for his pilgrimage to the Kaaba, leaving Réda to sleep in the car. In rare footage of thousands of white-robed Muslims descending upon the Great Mosque of which the director was granted filming rights, I am reminded of the full moon pradakshina around Mount Arunachala, such is the sheer density of humanity paying their reverential respects.

Later that evening, the hajjis return but Réda’s father is missing. The following morning, he searches in vain amidst a heaving sea of devotees, growing forever more anxious and frantic, finally being restrained and removed by security guards and taken away to a quiet, secluded room whereupon he discovers his father’s fate.

Photograph: © Pyramide Films

The final scenes are utterly heartbreaking and yet if we understand the inherent message of the Islamic teaching, the father does indeed find the peace and spiritual release he has been searching for. Even more significantly, Réda is completely transformed by the events of the hajj whereby his character metamorphosizes from feeling resentful, irate and rebellious into being compassionate, forgiving and loyal.

Moreover, as Fowzi Guerdjou’s musical score swells acoustically, along with our tear ducts, I similarly feel profoundly transformed by this mystical adventure into the deepest recesses of the soul. As with any holy expedition, we are forced to face the darkness within ourselves in order to facilitate the light.

Le Grand Voyage is thus the ultimate journey, transcending cultural barriers and filial boundaries, even the beliefs of faith itself, leading us unto the universality of the human spirit and the unity of immortal love.

“Labbayka Allāhumma Labbayk.

Here I am at Thy service O Lord.”