Polymath and mystic whose artistic and intellectual output was unsurpassed

And I saw as it were in the middle of the southern sky an image, beautiful and wonderful in the mystery of God, like a human in form. Her face was of such beauty and radiance that I could easier look at the sun than at her; and a great circlet of golden colour surrounded her head …

THERE ARE VERY few women, or even men for that matter, in the entire course of human history who can rival the sheer artistic and intellectual endeavour of that produced by the German mystic, writer, composer, philosopher and Benedictine abbess, Hildegard of Bingen (1098–17th September 1179).

Above that head, moreover, in the same circlet appeared another face like an old man, whose chin and beard touched the crown of the [lower] head. And from each side of the figure’s neck a single wing came forth, which rose up to join together above the aforementioned circlet …

[BSL, ms. 1942 : St. Hildegard, Liber divinorum operum].

Photograph: © 2017, Previa autorizzazione del Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività culturali e del Turismo – Biblioteca Statale di Lucca

[Reproduction or duplication by any means is expressly prohibited]

At the tip of the arc where the right wing curves back, I saw as it were the head of an eagle, which had eyes of fire, in which appeared the brilliance of the angels as in a mirror. But at the tip of the arc where the left wing curves back there was as it were a human face, which shined like the brilliance of the stars. And these faces were turned towards the east …

Hildegard was always keen to stress that her insights were nothing to do with dreams or trance or hallucination; rather, her experiences were viewed with her “inner eye” whilst she remained perfectly lucid throughout.

Furthermore, from each shoulder of this image, a single wing stretched forth down to her knees. She was clothed with a tunic like the brilliance of the sun, and in her hands she held a lamb, shining like the light of day …

Nevertheless, she suffered intense sickness during and after her visions, whereupon her body was pervaded by “aerial torments” and her womb consumed with an “ariel fire”.

Moreover, she was treading with her feet a monster, dreadful in appearance and venomous and black in color, and also a serpent that had fixed his mouth upon the right ear of the monster and, wrapping the rest of its body around the monster’s head, had stretched its tail along the monster’s left side all the way to its feet.

—Hildegard of Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum

Photograph: The Yorck Project,

[Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Literary works

Hildegard of Bingen was born at Bermersheim in Germany in 1098 into a well-established noble family and given as an “oblate” or offering to the Church at the age of eight, taking the veil a few years later. In 1150, inspired by a vision, Hildegard established her own independent nunnery at Rupertsberg on the Rhine, near the town of Bingen, where she was elected abbess.

Throughout her religious career, she undertook preaching tours and engaged in correspondence with all the major thinkers and theologians of her time. Most importantly, she embarked on a writing project of encyclopaedic proportions in order to systematize her experience of God and the nature of the human soul.

The soul in the body is like sap in a tree, and the soul’s powers are like the form of a tree … The intellect in the soul is like the greenery of the tree’s branches and leaves, the will like its flowers, the mind like its bursting first fruits, the reason like the perfected mature fruit, and the senses like its size and shape. And so a person’s body is strengthened and sustained by the soul. Hence, O human, understand what you are in your soul, you who lay aside your good intellect …

—Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias

Within the framework of the books, Hildegard addresses subjects as diverse as the nature of the cosmos and the meaning of the Trinity, as well as various ethical and social issues of the day. She also compiled non-mystical texts, in particular, two prose works entitled Causae et Curae and Physica, which focus on the natural world and medicine.

Illuminations

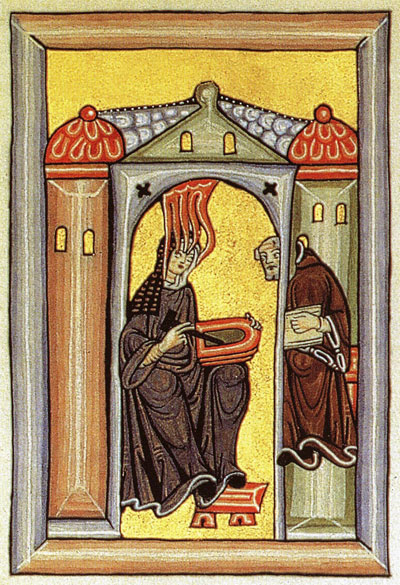

When Hildegard was in her seventies, she commissioned an illuminated manuscript to accompany the text of Scivias, now known as the Rupertsberg Codex; unfortunately, the manuscript was hidden for safekeeping during the Dresden bombings of 1945 and has never been seen since.

Thankfully, a hand-painted facsimile on parchment was made by the nuns of Eibingen during the 1920s and is a faithful representation. Various illustrations were also made in the early thirteenth century to illumine her other works, including Liber Divinorum Operum.

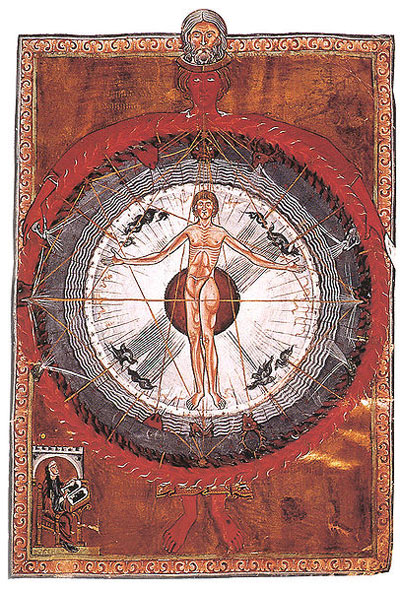

Not only do the illuminations possess all the ecclesiastical charm of mediaeval manuscripts with their bold colours and meticulous attention to detail, they also evoke comparisons with the relief etchings of the English poet, William Blake (1757–1827), through the use of fiery wings, coiling serpents and mythical beasts; moreover, Universal Man, an illustration for Liber Divinorum Operum, anticipates the later pen and ink masterpiece, Vitruvian Man, by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519).

Liber Divinorum Operum: Universal Man.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Comparisons with other mystical texts

Despite being of the Benedictine Order, Hildegard wrote in such a way that seemingly transcends her more traditional Roman Catholic inheritance, with passages sounding more akin to the Gnostic Gospels or even the Indian Upanishads:

And this image spoke: ‘I am the supreme and fiery force, who sets all living sparks alight and breathes forth no mortal things, but judges them as they are. Flying around the circling circle with my upper wings—with wisdom—I have ordered all things rightly.

‘But I am also the fiery life of the essence of divinity—I flame above the beauty of the fields and I shine in the waters and I burn in the sun, the moon, and the stars. With the airy wind I rouse to life all things with some invisible life, which sustains all things.

‘For the air lives in viridity and in the flowers, the waters flow as if they are alive, and the sun lives in its own light. When the moon has waned, it is rekindled by the light of the sun so that it might as it were live anew, and the stars shine bright by living as it were in their own light.

‘I have also established the pillars that contain the whole circle of the earth—the winds. The stronger winds have wings set below them, which are the lighter winds, and these uphold the stronger winds with their lightness, lest they dangerously unleash themselves; in the same way the body covers and contains the soul, lest it should expire.’

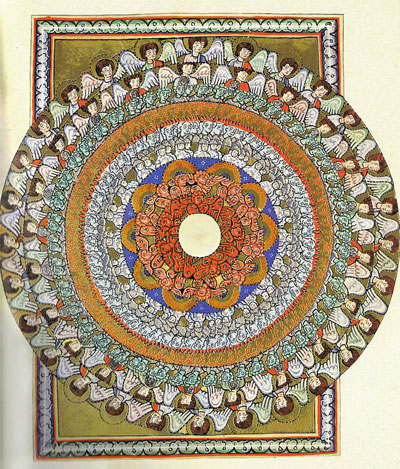

The True Trinity in True Unity.

Photograph: The Yorck Project,

[Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

‘Likewise, as the breath of the soul binds together the body by strengthening it so that it does not weaken, so the stronger winds also animate those subject to them, so that they can fulfil their duties appropriately.

‘Therefore I, the fiery force, lie hidden in these things, and they burn because of me, just as breath continually moves a human being and a flickering flame exists within the fire.

‘All of these things live in their essences and were not found in death, because I am life. I am also rationality, possessing the wind of the resounding Word, through which every created thing was made; and in all these things I blow, so that none of them might be mortal in its nature, because I am life.

‘For I am life, pure and whole, which was not hewn from stones, neither blossomed from branches nor took root from man’s sexual power; but every living thing has taken root in me. For reason is the root, and the resounding Word flourishes within it.’

—Hildegard of Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum

Musical compositions

As well as being blessed with the power of literary expression, Hildegard also had the gift of composing music, “the sacred sound through which all creation resounds”. For her, the soul was “symphonic” and resonated with the rhythms and harmonies of the universe.

Despite not having any musical training, she created choral music for the liturgy, written as texts with nuems (mediaeval musical notation), which are collected together in the Symphonia Armoniae Celestium Revelationum or Symphony of the Harmony of Celestial Revelations.

Hildegard’s music is commonly described as monophonic and melismatic; moreover, contemporary recordings of her songs reveal a haunting sophistication, often with melancholic undertones, more prevalent in modern chanting than mediaeval plainsong, making for a rich and enduring musical inheritance.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Hildegard’s legacy

Hildegard of Bingen lived a very long life and her creative output is almost unsurpassed. Regrettably, before she died, a scandal erupted in the nunnery at Rupertsberg involving the burial of a young nobleman—believed by the Church to have been excommunicated—in the convent cemetery.

The upshot of the affair was that the nuns were forbidden to take part in communion or to sing the liturgy. Although the situation was finally resolved by much pleading on Hildegard’s part, it left a bitter taste. After all, how could a respected abbess be subject to petty protocol after a lifetime’s service to God?

Hildegard died in 1179, aged eighty-one. Hers was a life imbued with courage and determination, in the face of ongoing religious and political misogyny. Moreover, her feisty persona gave her the strength not only to manage a thriving convent but also channel her spiritual visions into some of the most beautiful celestial music and illuminated prose ever to be produced.

In an era sadly wanting of any outstanding female role models, the spirit of Hildegard of Bingen is one to be both emulated and admired, empowering women—and men—to embrace their sacred selves.

Post Notes

- The Land of Hildegard of Bingen

- Saint Hildegard of Bingen

- Vision: From the Life of Hildegard von Bingen (film)

- Paula Marvelly: Sanctuaire Notre-Dame de Laghet

- Alexandra David-Néel: My Journey to Lhasa

- Alice Koller: An Unknown Woman

- Gospel of Mary Magdalene

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love

- Mahapajapati Gotami: Mother of All

- Eric Nicholson: William Blake’s Vision of the Book of Job

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Michael Molinos: The Spiritual Guide