Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

A voyage to the edge of despair

“For our goal was not only the East, or rather the East was not only a country and something geographical, but it was the home and youth of the soul, it was everywhere and nowhere, it was the union of all times.”

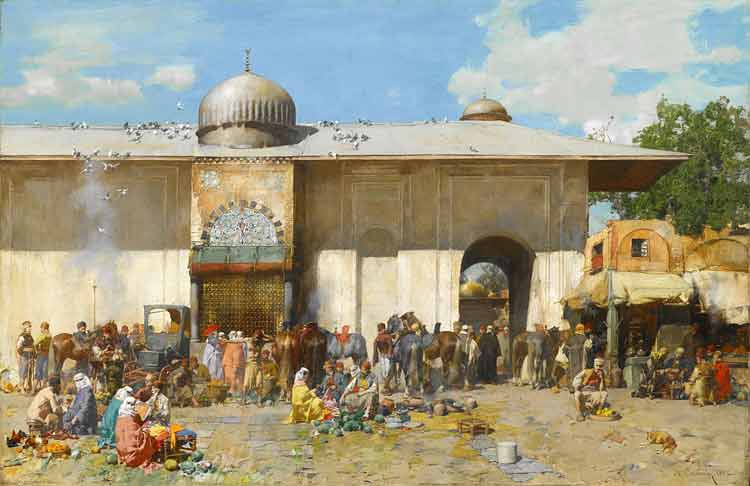

LIKE MANY PEOPLE who are disillusioned with Western society and turn to the East for spiritual nourishment, the writings of Hermann Karl Hesse (2nd July 1877–9th August 1962) have formed an intrinsic presence in my quest for self-discovery and inner peace. I have devoured all his novels over the years, marvelling at how he manages to combine literary sensibility with mystical depth.

The Journey to the East (Die Morgenlandfahrt) (1932) is a novella, written as a preliminary study to his final masterpiece, The Glass Bead Game, shortly after which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946. Narrated by H.H., it is the tale of a philosophical sect called the League comprising writers, musicians and artists, who travel through space and time, meeting illustrious personages both imaginary and real—including Plato, Mozart, Paul Klee, Baudelaire—in search of the ultimate truth during the aftermath of the Great War.

I realized that I had joined a pilgrimage to the East, seemingly a definite and single pilgrimage—but in reality, in its broadest sense, this expedition to the East was not only mine and now; this procession of believers and disciples had always and incessantly been moving towards the East, towards the Home of Light. Throughout the centuries it had been on its way, towards light and wonder, and each member, each group, indeed our whole host and its great pilgrimage, was only a wave in the eternal stream of human beings, of the eternal strivings of the human spirit towards the East, towards Home. The knowledge passed through my mind like a ray of light and immediately reminded me of a phrase which I had learned during my novitiate year, which had always pleased me immensely without my realizing its full significance. It was the phrase by the poet Novalis, ‘Where are we really going? Always home!’

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Over the ensuing years, he tries to make sense of the calamity by composing a narrative; immediately he warns the reader, however, that this will be a difficult task.

As it has been my destiny to take part in a great experience, and having had the good fortune to belong to the League and allowed to share in that unique journey, the wonder of which blazed like a meteor and afterwards sank into oblivion—even falling into disrepute—I have now decided to attempt a short description of this incredible journey …

I have allowed myself no illusions as to the difficulties involved in such an attempt. They are very great, and are not only subjective, although these in themselves would be considerable enough. For not only do I no longer possess the tokens, mementoes, documents and diaries relating to the journey, but in the difficult years of misfortune, sickness and deep affliction which have elapsed since then, many of my recollections have also vanished. As a result of the blows of Fate and continual discouragement, my memory as well as my confidence in these earlier vivid recollections have become impaired. But apart from these purely personal notes, I am handicapped because of my former vow to the League; for although this vow permits unrestricted communication of my personal experiences, it forbids any disclosures about the League itself. And even though the League seems to have had no visible existence for a long time and I have not seen any of its members again, no allurement or threat in the world would induce me to break my vow. On the contrary, if today or tomorrow I had to appear before a court martial and was given the option of dying or divulging the secret of the League, I would joyously seal my vow to the League with death.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Moreover, in similar vein to Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s eponymous Ivan Karamazov, the character of H.H. suffers an acute existential crisis in his attempts to make any kind of sense of what has happened to him, fearing he has lost all meaning to life as well as the will to live. Confiding in his friend, Lukas, he believes that writing alone, not least his memoir of the League, will save him, perhaps echoing a sentiment about the cathartic nature of composition held by Hermann Hesse himself.

Lukas advises H.H. to find Leo and put an end to his mental torment and, after discovering his name listed in the local directory, he follows Leo one afternoon as he takes a stroll from his apartment to sit on a park bench and eat some dried fruit. Their ensuing conversation—Leo apparently has no recollection of his former League member—devastates H.H., who rushes home in the encroaching rain to compose a letter to him, which he posts that very same evening.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

I had experienced similar hours in the past. During such periods of despair it seemed to me as if I, a lost pilgrim, had reached the extreme edge of the world, and there was nothing left for me to do but to satisfy my last desire: to let myself fall from the edge of the world into the void—to death. In the course of time this despair returned many times; the compelling suicidal impulse, however, had been diverted and had almost vanished. Death was no longer nothingness, a void, negation. It had also become many other things to me. I now accepted the hours of despair as one accepts acute physical pain; one endures it, complainingly or defiantly; one feels it swell and increase, and sometimes there is a raging or mocking curiosity as to how much further it can go, to what extent the pain can still increase.

All the disgust for my disillusioned life which, since my return from the unsuccessful journey to the East, had become increasingly worthless and spiritless, all belief in myself and my abilities, all envious and regretful longing for good and great times which I had once experienced, grew as high as a tree, like a mountain, tugged at me, and was all related to the former task that I had begun, to the account of the Journey to the East and the League. It now seemed to me that even its accomplishment was no longer desirable or worthwhile. Only one hope still seemed worthwhile to me—to cleanse and redeem myself to some extent through my work, through my service to the memory of that great time, to bring myself once again into contact with the League and its experiences.

When I reached home I turned on the light, sat down at the desk in my wet clothes, my hat on my head, and wrote a letter. I wrote ten, twelve, twenty pages of grievances, remorse and entreaty to Leo. I described my need to him, conjured up images of our common experiences, of our former mutual friends. I bewailed the endless extreme difficulties, which had shattered my noble enterprise. The weariness of the moment had disappeared; excited, I sat there and wrote. Despite all difficulties, I wrote, I would endure the worst possible thing rather than divulge a single secret of the League. Despite everything, I would not fail to complete my work in memory of the Journey to the East in glorification of the League. As if in a fever, I covered page after page with hastily written words. The grievances, indictments and self-accusations tumbled from me like water from a breaking jug, without reflection, without faith, without hope of reply, only with the desire to unburden myself. While it was yet night I took the thick, confused letter to the nearest letterbox. Then, at last, it was nearly morning. I turned out the light, went to the small attic bedroom next to my living room and went to bed. I fell asleep immediately and slept very deeply for a long time.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

With reminiscences of Franz Kafka’s The Trail, the Speaker pronounces to H.H. that the events that had transpired at Morbio Inferiore were, in fact, a test of his allegiance to the League, a test which, sadly, he had irrefutably failed. Moreover, the subsequent despair and desertion were a further assessment of his character and an inherent part of the process to the second stage of membership. Despite his transgressions, H.H. is absolved of his selfish and ignorant crimes and readmitted into the unified collective of the League. The true identity of the humble servant, Leo, is also then revealed to be the President of the League himself. (Hermann Hesse had a great admiration for Saint Francis of Assisi, whose favourite true servant companion and soul friend was Brother Leo.)

H.H. is then left on his own in the archives, whereupon he reads the various accounts of the League’s members who were with him on that fateful day in Morbio Inferiore. Each account is completely different and at odds with the others, including his own. He has the sudden realization that any written report of an event can only ever be subjective interpretation, not the objective truth.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

A shudder went through me at the thought of what I should still learn in this hour. How awry, altered and distorted everything and everyone was in those mirrors, how mockingly and unattainably did the face of truth hide itself behind all the reports, counter-reports and legends! What was still truth? What was still credible? And what would remain when I also learned about myself, about my own character and history from the knowledge stored in these archives?

I must be prepared for anything. Suddenly I could bear the uncertainty and suspense no longer. I hastened to the section Chattorum res gestae, looked for my subdivision and number and stood in front of the part marked with my name. This was a niche, and when I drew the thin curtains aside I saw that it contained nothing written. It contained nothing but a figure, an old and worn-looking model made from wood or wax, in pale colours. It appeared to be a kind of deity or barbaric idol. At first glance it was entirely incomprehensible to me. It was a figure that really consisted of two; it had a common back. I stared at it for a while, disappointed and surprised. Then I noticed a candle in a metal candlestick fixed to the wall of the niche. A matchbox lay there. I lit the candle and the strange double figure was now brightly illuminated.

Only slowly did it dawn upon me. Only slowly and gradually did I begin to suspect and then perceive what it was intended to represent. It represented a figure which was myself, and this likeness of myself was unpleasantly weak and half-real; it had blurred features, and in its whole expression there was something unstable, weak, dying or wishing to die, and looked rather like a piece of sculpture which could be called ‘Transitoriness’ or ‘Decay’, or something similar. On the other hand, the other figure which was joined to mine to make one, was strong in colour and form, and just as I began to realize whom it resembled, namely, the servant and President Leo, I discovered a second candle in the wall and lit this also. I now saw the double figure representing Leo and myself, not only becoming clearer and each image more alike, but I also saw something moving, slowly, extremely slowly, in the same way that a snake moves which has fallen asleep. Something was taking place there, something like a very slow, smooth but continuous flowing or melting; indeed, something melted or poured across from my image to that of Leo’s. I perceived that my image was in the process of adding to and flowing into Leo’s, nourishing and strengthening it. It seemed that, in time, all the substance from one image would flow into the other and only one would remain: Leo. He must grow, I must disappear.

As I stood there and looked and tried to understand what I saw, I recalled a short conversation that I had once had with Leo during the festive days at Bremgarten. We had talked about the creations of poetry being more vivid and real than the poets themselves. The candles burned low and went out. I was overcome by an infinite weariness and desire to sleep, and I turned away to find a place where I could lie down and sleep.

And thus the ultimate truth is finally revealed to H.H.; that he must yield, submit, nay die unto that unifying, continuously flowing substance, personified by the humble servant and President Leo. It is only through service, faith, humility and the transcendence of individual ego can there ever be an awakening of the “home and youth of the soul”, releasing H.H. from the depths of utter despair and leading him back towards the East, towards the Light, towards Home.

Post Notes

- Hermann Hesse Portal

- E. M. Forster: The Celestial Omnibus

- Alexandra David-Néel: My Journey to Lhasa

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- Ray Brooks: The Shadow That Seeks the Sun

- Alan Watts: Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown

- René Daumal: Mount Analogue