Photograph: © Michel Sima/Lebrecht Music & Arts

Sisterly love

“Most painters … look for an external light to see clearly into their own nature. Whereas the artist or the poet possesses an inner light that transforms objects, creating a new world within them, a sentient, organized and living world, a sure sign of divinity in itself, the reflection of divinity.”

—Henri Matisse

IT IS ALWAYS interesting to me how the ineffability of the nondual state, despite being the substratum of all that exists, can have so many flavours and nuances. Being in a church or chapel, a crucible for the human spirit to meld with the Creator, more often of late brings me to a profound stillness and yet I similarly sense myriad modulations of meaning and mood.

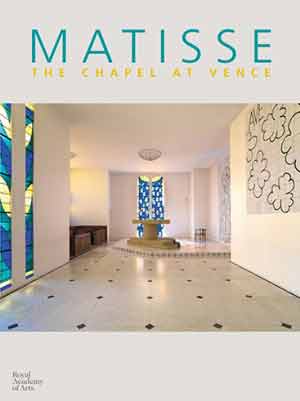

Henri Matisse’s Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence is the final port of call on my artistic odyssey. Located in an unobtrusive French street on the road out of Vence leading up into the hills, its understated atmosphere is in stark contrast to the majestical grandeur of the Sacra di San Michele in Turin and the quirky uniqueness of Jean Cocteau’s Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer.

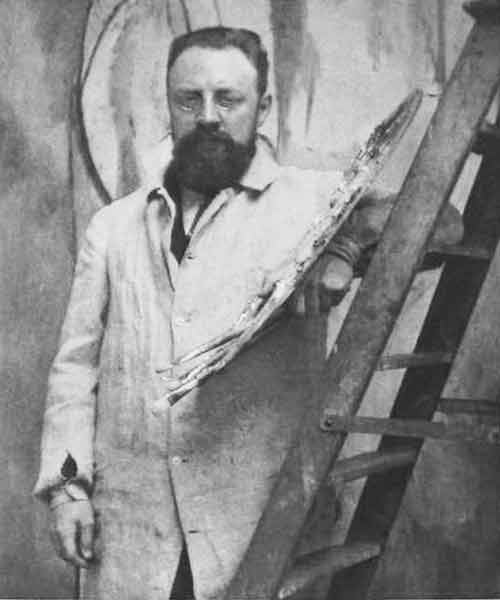

Interestingly, Henri-Émile-Benoît Matisse (31st December 1869–3rd November 1954) was for most of his life an atheist but the project of constructing and designing the chapel in its entirety would bring out a deeply spiritual aspect in his psyche and lead him to declare upon its inauguration in 1951 that La Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence was the crowning achievement of his entire career.

Photograph: © Royal Academy of Arts, London

I want those who enter my chapel to be purified and relieved of their burdens.

—Henri Matisse

Whilst recovering from an operation for bowel cancer at his home, Le Rêve, in Vence, Matisse was nursed by a young woman, Monique Bourgeois, who would later become a Dominican nun, Sister Jacques-Marie. As there was no chapel at her convent, Foyer Lacordaire, in order to thank her for her devoted care towards him, he decided to build her one instead. And thus he set about at the age of 77 creating a serene space that would become the masterpiece of his artistic endeavour.

Sitting inside the chapel, the crisp morning sunlight refracting and scattering over the white tiles a kaleidoscopic montage of blue and green and yellow, I feel not only is this the pinnacle of Matisse’s virtuosity but also any twentieth-century visual artist that I have ever had the privilege to behold.

Moreover, there is a dignity and stillness rendering the chapel a reverential transcendence to all that is otherworldly, leaving you alleviated of mental and emotional suffering, and returning you to a pristine, almost preternatural state.

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 3.0] Wikimedia Commons

The artist’s conscience is a pure, faithful mirror in which he must be able to reflect his work every day … The abiding responsibility of the creator towards himself and towards others is not a hollow concept: by assisting the universe to construct itself the artist maintains his dignity.

—Henri Matisse

At the back of the church are the almost childlike outlines of the Stations of the Cross, black silhouettes painted on white tiles, a concatenation of pain and tribulation. And yet in direct antithesis on the opposite wall is a magnificent stained-glass window, depicting the Tree of Life, its foliage flickering within the sun’s rays and radiating a resplendent glow.

It is the profound positioning of Christ’s suffering behind me and the hope of redemption ahead that makes the architectural layout the very embodiment of our individual journeys on this earth. Indeed, the focus of the chapel is not the pain of crucifixion but rather the glory of everlasting life.

Matisse himself struggled all his career with moments of inner turmoil and sought to find a modicum of peace and tranquillity within his art. He is said to have asked himself, “Do I believe in God? Yes, when I work.”

Photograph: © Royal Academy of Arts, London

Preparing the work itself means first nourishing one’s feelings through studies representing a certain analogy with the work; it is then that the choice of elements can be made. It is these studies that enable the painter to give free rein to his subconscious … After a certain point, it is no longer up to me, it is a revelation: all I do is give myself up.

—Henri Matisse

Stepping out onto the terrace, I carry within me the sacredness of the chapel, my very soul soothed by the legacy of Matisse’s craft. The late morning sunshine illumines Saint Paul de Vence straight ahead of me, the legendary ancient Provençal village, faintly reminding me of Sacra di San Michele, its epicentral tower in touch with the void above.

I am bathed in overwhelming beauty and feel giddy with awe. Then I think to myself, if all manifest phenomena is an illusion, why am I so deeply affected by that which I perceive to be visually attractive and harmonious of form?

More specifically, why don’t I feel this way in my day-to-day existence and remain forever plagued by lethargy, despair and ennui. Why do I need art and all things timeless, wise and beautiful to uplift and ennoble me to be my true self?

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 3.0] Wikimedia Commons

This is not work I chose but rather work for which I was chosen by fate when at the end of my road, one that I pursue through my research. The chapel provided me with an opportunity to set it down by combining its various features.

—Henri Matisse

The German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, who championed the notion that art could offer deliverance from the Will, said, “… aesthetic pleasure in the beautiful consists, to a large extent, in the fact that, when we enter the state of pure contemplation, we are raised for the moment above all willing, above all desires and cares; we are, so to speak, rid of ourselves.”

Moreover, he effectively turned art into a substitute religion by offering a doctrine of salvation through aesthetic experience. Artists are thus raised to the level of priests and prophets as custodians of the visual apperception of the nondual state.

Indeed, like so many fellow travellers weary of intellectual debate and academic pedantry, I yearn for an ongoing experiential and intimate convergence with That which is both without and within me, and gives life some kind of meaning and sense.

Photograph: © Royal Academy of Arts, London

At the moment I go every morning to say my prayers, pencil in hand; I stand in front of a pomegranate tree covered in blossom, each flower at a different stage, and I watch their transformation. Not in fact in any spirit of scientific enquiry but filled with admiration for the work of God. Is this not a way of praying? And I act in such a way (although basically I do nothing myself as it is God who guides my hand) as to make the tenderness of my heart accessible to others.

—Henri Matisse

My heart is open; my mind is stilled; my soul is purged … My road trip is finally over; I’ve paid homage to the alchemical masters of art—Jean Cocteau, Henri Matisse, the anonymous Benedictine monks—who have touched me in so many myriad ways that I am fundamentally and profoundly changed. Now I must return to the seemingly mundane world of my daily life and all that entails.

And yet I can already feel the urge stirring within me to seek out further adventure and bask once again in those precious moments where I am rid of myself and am in touch with the light and divinity within.

Post Notes

- HenriMatisse.org

- Jean Cocteau: Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer

- Paul Cézanne: La Montagne Sainte-Victoire

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- Paula Marvelly: Sanctuaire Notre-Dame de Laghet

- Paula Marvelly: Sacra di San Michele

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora

- Marc Chagall: All Saints’ Tudeley