Airbrushed acrylic and oil on linen,

30” x 36”.

Image: © Robert Martinez (Northern Arapaho)

Restoring our world through a Sacred Harmony

with the earth and each other

“Let every step you take upon the earth be as a prayer.”

—Black Elk, Oglala Lakota holy man

THE WORK OF CARAVAN—an international arts nonprofit/NGO that is recognized as a leader in using the arts to transform our world—is no stranger to The Culturium. Founded and curated by Rev. Canon Paul G. Chandler, their seminal exhibition focusing on the work of Middle Eastern artists drawing inspiration from Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet is one of the most popular pieces on the site.

The current Bishop of the Episcopal Church in Wyoming, USA, Paul-Gordon has now taken lead from the artists of the Great Plains by bringing together an exhibition in a partnership between CARAVAN and ArtSpirit, the church’s own arts initiative, celebrating the heritage and wisdom of Native Americans, whose spirituality was first brought to international attention nearly a century ago through the words of Oglala Lakota holy man, Black Elk.

Grounded in a love of the natural world, 15 contemporary artists have paid homage to their cultural roots by evoking the creative spirit of their ancestors, bestowing sacred reverence to animals, birds, rivers, the clouds in the sky, even the dirt of the earth. Humans, too, are exalted, with equal veneration given to both men and women as reflecting the image of Creator. In a time period when our collective past is being wholly re-examined in light of the lessons and insights it has to offer us, ArtSpirit and CARAVAN’s initiative couldn’t be more timely.

GROUNDED is an artistic exploration in partnership with ArtSpirit that brings together 15 premier and emerging contemporary artists from eight Indigenous American tribes traditionally based in and around the Great Plains region of the USA, seeking to inspire our imaginations about our need to be ‘grounded’ in our relationship with all of creation: the earth and its wildlife, each other and ourselves.

It is critical for the health and survival of our planet that we acknowledge and honour our intricate connection to the earth as our sustainer, to the wisdom of our ancestors, and to humanity’s need of each other. Our world itself is calling for a realignment of a sacred harmony and an awareness of a new balance between ourselves and the earth, and with all of life upon it.

We have much to learn from the Indigenous cultures of our Native American sisters and brothers about being grounded in the interconnectedness of the sacred, the natural world, and one another. Native American traditional beliefs see everything on the earth as living in relationship. Seeing the interconnectedness of all things, they understand today’s environmental and humanitarian crises as affecting everyone and everything—geologically, physically, emotionally and spiritually.The artistic practice of the inspiring group of 15 Native American artists is a unique blend of their heritage and creative expression. Their work serves as a visual representation of the worldview, wisdom and learnings of their forebears, which is urgently needed today as we reimagine the way we live in order to heal our world. Their spiritual wisdom is, therefore, essential toward developing a ‘sacred harmony’ between all peoples and with the earth. This unique contemporary art exhibition seeks to enable them to share their culture, heritage and sacred traditions to help us restore our world and foster wholeness among all peoples. The exhibition is curated by noted Northern Arapaho artist, Robert Martinez (Northern Arapaho).

—Rev. Canon Paul G. Chandler

Bishop of the Episcopal Church in Wyoming & Founder of CARAVAN

Acrylic on ledger paper,

25” x 25”.

Image: © Jim Yellowhawk (Itazipco/Cheyenne River Sioux)

To be grounded myself, I need to have a spiritual connection with the universe. The eagle messengers send my prayers in the four directions, from Unci Maka, ‘Mother Earth’. The rainbow is a symbol of hope and the dragonfly is also a messenger to the Wicahpi Oyate, ‘Star Nation’.

—Jim Yellowhawk

Itazipco/Cheyenne River Sioux

Acrylic painting on antique ledger paper with gold leaf accents,

19.5” × 15.5”.

Image: © Talissa Abeyta (Eastern Shoshone)

My grandma always reminds me of how prayer repeatedly saved our people. Our ceremonies and respecting Mother Earth kept life balanced. The Sundance came to us when were in a time of need. They say Yellow Hand was praying and fasting for an answer to save his people. A buffalo appeared swaying his head and gifted Yellow Hand our songs. My painting is about how the Sundance was brought to Yellow Hand … I kept the various elements minimal so that the key components were accentuated.

—Talissa Abeyta

Eastern Shoshone

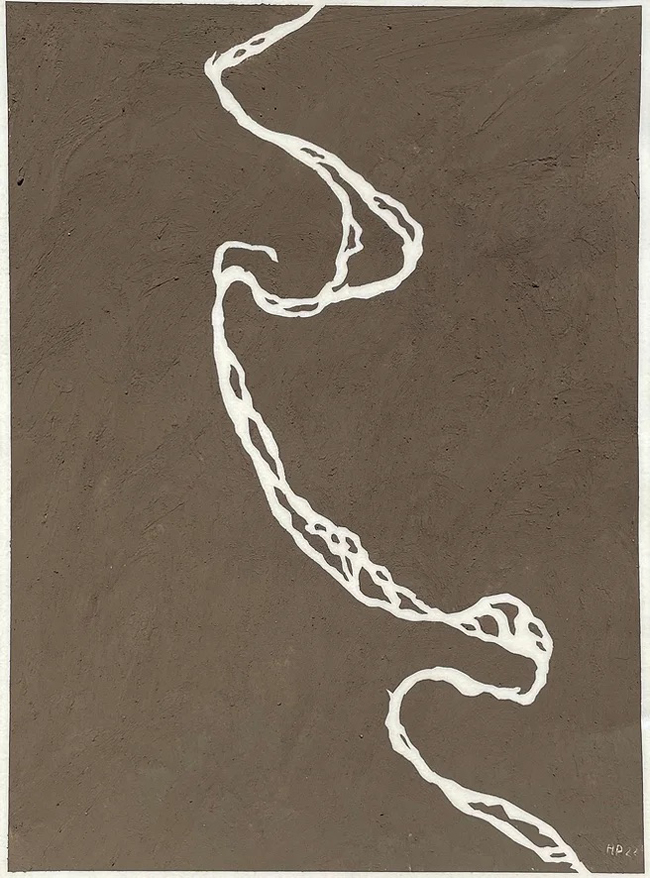

Njjsoceja (Muddy Water)—Missouri River/Thurston County, , 2022

Land collected from the Winnebago Indian Reservation on rawhide,

12′ x 16″.

Image: © Henry Payer (Ho-Chunk)

This work references an 1890 map of the Missouri River in Thurston County where the Winnebago Indian Reservation is located. I gathered land (dirt) from the reservation to act as the medium to map our territory before the Army Corps of Engineers rerouted the Missouri River in the 1960s, thus reducing the number of acres belonging to the Tribe. This work serves to place precedence on Land and our struggle to have access to different traditional cultural properties located throughout our history of removal and relocation.

Having access to our land allows us to be self-sustainable, to live grounded, and accommodate necessities from the land, including hunting for food, gathering medicine and having room to practise ceremonies. The use of rawhide is one of these many natural resources and acts as a connection to our ancestors of the Great Plains’ artistic aesthetic through a contemporary lens.

—Henry Payer

Ho-Chunk

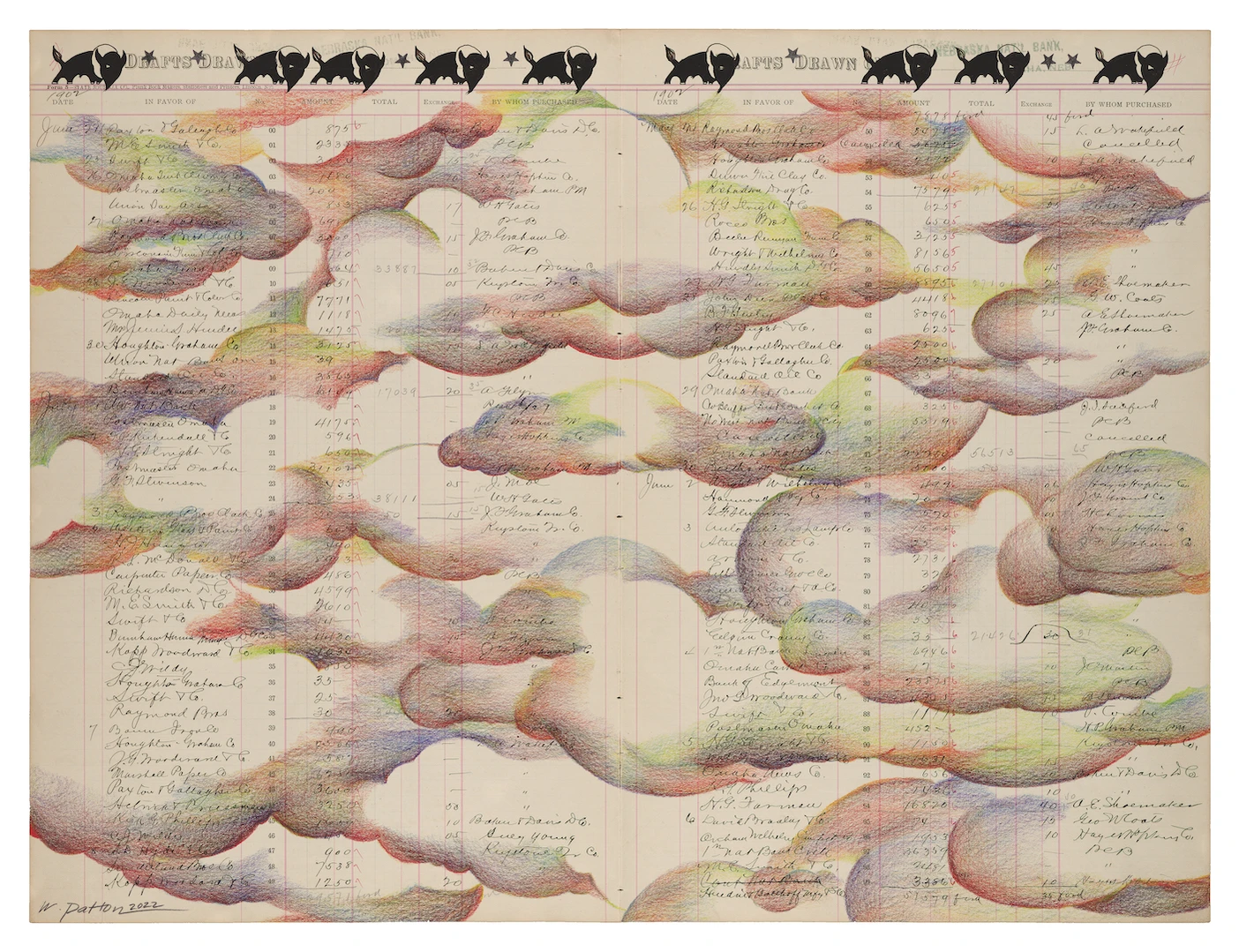

Graphite, micron ink, coloured pencil/original 1902 ledger page,

20.62” x 15.25”.

Image: © Wade Patton (Oglala Lakota)

In Above Ground, I bring the influence of the skies of South Dakota into my artwork, which is the source of inspiration in most of my work. In this particular piece, numbers represent my heritage, Oglala Lakota. The nine buffaloes represent the nine districts of Oglala Lakota County in South Dakota. The seven values of the Lakotas, which encourage a sense of harmony with Creation, oneself and others are indicated by the stars: Praying, Respect, Caring, Honesty, Generosity, Humility and Wisdom.

—Wade Patton

Oglala Lakota

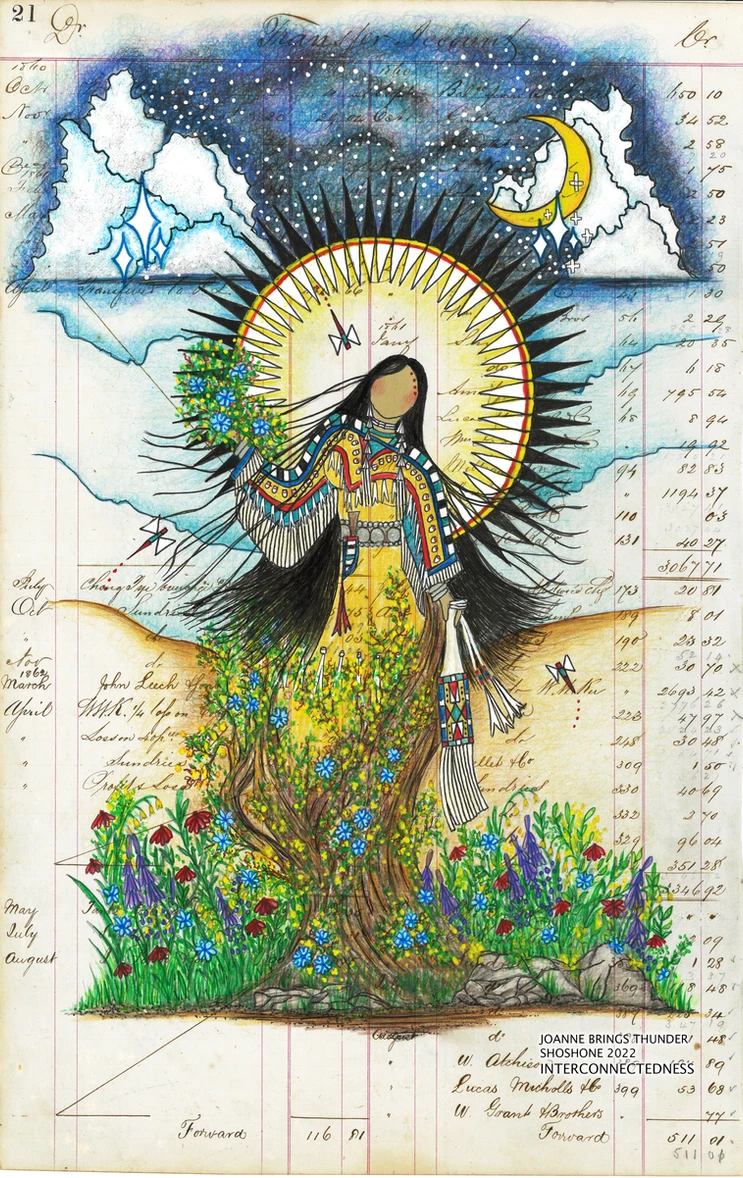

Acrylic paint, ink, coloured pencil on antique ledger paper dated 1810,

11” x 17”.

Image: © Joanne Brings Thunder

For Shoshone people, the concept of ‘interconnectedness’ is at the core of our view of the world. We believe everything in the universe is connected and that every person, creature, plant and object has a purpose; all deserve to be respected and cared for, and have an important role to play in the overall script of life. Our people are tightly connected to their communities, to their ancestors, to future generations, and to the lands and environment in which live. We share a sacred connection to animals, plants and even inanimate objects that reside on these lands.

Prior to contact with European explorers, traders and settlers, Shoshone lived in harmony with their natural environment. Their practices were based on acute awareness, and knowledge of ecology, the need for sustainability, climate, and earth science. This knowledge has, through thousands of years, been shared with subsequent generations, allowing us to love and demonstrate environmental responsibility by respecting the ideas of sustainability and continuous relationships. The earth is sacred, part of a ‘web of creation’. Humans are also part of this web and share a close relationship with nature, rather than control it.

—Joanne Brings Thunder

Eastern Shoshone

Acrylic on canvas,

18” x 14”.

Image: © Brent Learned (Arapaho/Cheyenne)

When you lose the rhythm of the drumbeat of God, you are lost from the peace and rhythm of life.

The buffalo was everything to the Plains Indians. The Plains Indian tribes survived on hunting all types of game, such as elk and antelope, but the buffalo was their main source of food. Every part of the buffalo was used and nothing went to waste. In addition to providing food, the Indians used the skins for tipis and clothing and hides for robes, shields, and ropes. They used dried buffalo dung for fuel, made tools, such as horn spoons, scrapers from bone; sinew or muscle was used to make bowstrings, moccasins, and bags, and the hoofs were used to make glue.

Following the seasonal migration of the buffalo, the tipis that the Plains Indians lived in were ideal for their nomadic lifestyle. The buffalo had well over 100 uses. The Plains Indian would follow the buffalo and sometimes fight other tribes over hunting grounds. You only hunted when you needed food and you never hunted the Buffalo without a ceremony. Killing a buffalo without permission from the elders of the tribe would bring bad medicine to the tribe and usually, that person was exiled from the tribe.

—Brent Learned

Arapaho/Cheyenne

Oil on canvas,

24” x 18”.

Image: © Louis Still Smoking (Blackfeet)

Duality is a portrait of a Crow woman named Julia Bad Boy-Bear Ground. Its composition speaks to the truth of how Native peoples live in two worlds, two different cultures. One is the natural world. The other is the modern world. The modern world is ever-changing, whether it be medicine, technology, or culture. While holding onto our indigenous identity for a sense of grounding, we tread on both paths with grace.

—Louis Still Smoking,

Blackfeet

“Great Spirit … All things belong to you—the two-legged, the four-legged, the wings of the air and all green things that live. You have set the powers of the four quarters to cross each other … and where they cross, the place is holy. Day in and day out, forever, you are the life of things.”

—Black Elk, Oglala Lakota holy man

Post Notes

- CARAVAN

- ArtSpirit

- Rev. Canon Paul G. Chandler’s website

- The Episcopal Church in Wyoming

- Paul G. Chandler: The Canvas of Life

- SYMBOLS OF LIFE: Beyond Perception

- NOAH: A Future Hope

- Hady Boraey: Line of Descent

- Abraham: Out of One, Many

- Kahlil Gibran: Poet, Painter, Prophet

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art