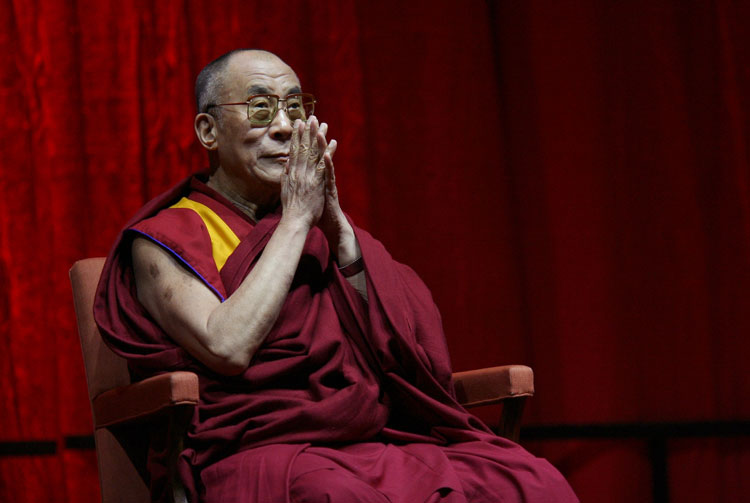

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Western pathways to emptiness

Greg Goode is the author of popular books on spirituality, including Standing As Awareness, The Direct Path, Emptiness and Joyful Freedom and After Awareness. Greg is a former book critic, bibliographer and film reviewer.

In The Culturium’s latest guest post, Greg and Tomas investigate occidental gateways to discovering the impermanence of all changing phenomena and the end of mental suffering.

The explorers slash their way through the jungle. They see a small animal run through the clearing ahead, followed by a hunter who calls out, ‘Gavagai!’

‘How do you translate “gavagai” into English?’ asks the American field linguist.

‘I just saw a rabbit hopping by, so I’m guessing that “gavagai” means “rabbit”,’ said the safari leader.

‘Well, couldn’t it just as easily mean “rabbit god” or “He’s running too fast”? says the linguist. ‘How would you know the difference?’

THIS VIGNETTE IS inspired by Harvard philosopher, W. V. O. Quine [1.]. It dramatizes the question, “How do we learn a language from scratch?” Quine argues that the linguist must proceed by working with a local informant. The linguist must test by trial and error. She’ll utter a sentence under various conditions and try to get assent or dissent from the informant. Say a rabbit walks by instead of running. She’ll perhaps ask the informant, “Gavagai?” and begin to collate responses. Of course even interpreting the informant’s assent is not unambiguous. How does the linguist even know what signals “yes” and “no”?

Quine argues that no matter how many additional observations are collected, the linguist will never be able to translate into her own language without ambiguity. In Western philosophy this has been called the thesis of the “indeterminacy of translation”. There are always multiple possible translations. There is always some ambiguity in meaning. Different translations will seem more or less plausible depending on different factors, including contexts and conceptualizations.

Emptiness

Quine’s insight about indeterminacy is similar to a fundamental teaching we find in Buddhism. It’s the teaching sometimes called “emptiness” or “dependent arising” (from the Sanskrit, pratītyasamutpāda). According to this radical way of experiencing the world, things are “empty” of inherent existence and independence. Things and the self aren’t experienced as being autonomous, static, self-sufficient or mind-independent. Instead, they depend on an infinite number of conditions and other things.

Seeing things as empty flies in the face of our usual experience. Usually, we imagine the self and worldly phenomena to exist in a very non-empty way, as if they rest on firm, objective foundations. According to Buddhism, when we suffer, it is because these projections are out of synch with the empty nature of phenomena. But when we realize emptiness we bring the mind into accord with reality and experience peace and happiness. This is why in Buddhism, deeply realizing the self to be empty is taught as the key to lasting happiness.

But happiness is not for one’s self alone. The meditator also works on kindness. Cultivating sincere kindness towards others is indispensable to the deep realization of emptiness. In Buddhism, emptiness and compassion are treated as two aspects of the same loving way of life. When we meditate on either one, we grow in both.

Before further discussing the nature of emptiness, let’s talk about its scope.

That is, which things are empty? How far does emptiness go? Actually, no non-empty things can be found. This includes Quine’s translation and meaning, as well as everyday objects. Most significantly, our very selves are empty. Even emptiness is empty, by depending on other things. In Buddhism, it is crucial to realize the emptiness of the self, which is the most prominent phenomenon in our lives. But towards that end, we must also realize the emptiness of phenomena related to the self. When we take this far enough, it includes everything. And indeed, in the most profound emptiness realizations, nothing is left out.

With this interdependence in mind, when we look at how something exists, we find relatedness, not independence. What we’re looking at is related to other things in many ways. It’s even related to our looking at it! In this teaching, we don’t think of things as individual or static lumps of pre-formatted stuff. A popular metaphor for relatedness compares things to jewels in Indra’s Net of Jewels. Each eye in the net contains a sparkling jewel, which reflects all the others [2.].

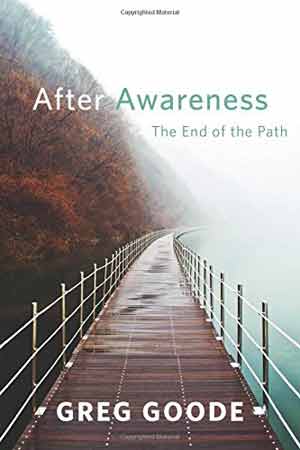

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 2.0] Wikimedia Commons

If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud, there will be no rain; without rain, the trees cannot grow, and without trees we cannot make paper. The cloud is essential for the paper to exist. If the cloud is not here, the sheet of paper cannot be here either … If we look into this sheet of paper even more deeply, we can see the sunshine in it. If the sunshine is not there, the forest cannot grow. In fact, nothing can grow. Even we cannot grow without sunshine. And so, we know that the sunshine is also in this sheet of paper …

The paper and the sunshine inter-are. And if we continue to look, we can see the logger who cut the tree and brought it to the mill to be transformed into paper. And we see the wheat. We know that the logger cannot exist without his daily bread, and therefore the wheat that became his bread is also in this sheet of paper. And the logger’s father and mother are in it too … You cannot point out one thing that is not here—time, space, the earth, the rain, the minerals in the soil, the sunshine, the cloud, the river, the heat. Everything co-exists with this sheet of paper … As thin as this sheet of paper is, it contains everything in the universe in it.

Most of what we hear about emptiness as a spiritual teaching comes from Buddhism. In Buddhism, our selves and all other phenomena are said to be empty of the kind of exaggerated, independent existence we attach to them. Realizing emptiness is taught as a way to unleash profound freedom. When we realize that selves and phenomena don’t exist as solidly as we think they do, our clinging is reduced. It is said that in cases of very deep realization, suffering is completely eradicated.

Emptiness in Buddhism

How does Buddhism explain emptiness? Different Buddhist schools emphasize different kinds of answers. Meditators may focus on pointers, such as the impermanence of constantly changing phenomena, the unfindability of a solid self, or the “great doubt” experienced in koan study. Another approach to emptiness uses study and reasoning. Drawing inspiration from the work of Nagarjuna and Chandrakirti, Tibetan monks devote much of their monastic education to it.

We, Greg and Tomas, have found the method of reasoning very powerful. Reasoning can apply to everyday things like tables and chairs, as well as to subtle things like standards of beauty or what it means to claim that one spiritual path is “higher” than another. The insight gained from emptiness reasonings can transfer from one thing to another. It can even be generalized to all things. And it doesn’t depend on our feelings or mood.

Because the Buddhist emptiness sources are centuries old, their meditations refer to things like seeds, sprouts and chariots. I’m sure that these were intuitive, familiar, everyday objects in their day. But they don’t feel as familiar these days. Here are two well known examples:

“Seed and sprout” meditation on causality or production: “Is something produced from itself or from something different? Does a seed produce a sprout or is a sprout produced from itself? Are a seed and a sprout the same thing or different things?”

“Chariot” meditation on identity: “Just what is the chariot? Is it the same as its parts or different? Is it dependent upon its parts? Are the parts dependent upon it? Is it the possessor of its parts? Is it a mere collection of parts? Is it the shape of the parts?

Some meditations, like this one on movement, are very abstract. They’re hard to understand and hard to apply in everyday life:

“Movement”, a metaphor for change: “What has been moved is not moving. What has not been moved is not moving. Apart from what has been moved and what has not been moved, movement cannot be conceived.” [3.]

For most students, these kinds of meditations require lots of unpacking to become relevant and helpful. The ideal situation would be a small class setting with an insightful teacher. The teacher could explain the meditations, apply them to everyday issues and answer questions. But these situations aren’t easy to find, even on YouTube!

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Emptiness meditations from Western sources

In our book, Emptiness and Joyful Freedom [4.], we tried to modernize the meditations and make them more user-friendly for a contemporary audience. We added meditations from psychology, neuroscience and philosophy. We feel that these modern meditations do a better job of addressing modern Western maladies, such as issues of identity, self-esteem, meaning, truth and the diversity of spiritual teachings. And even for students working in a traditional Buddhist framework, these meditations may serve as additional tools to deepen their insights into emptiness.

Some people wonder quite rightly how any philosophy can lead to personal transformation. Isn’t philosophy too dry? It certainly is dry for some people but not for everyone. Philosophy has a good track record in Buddhism, as well as in other transformational paths, such as Advaita Vedanta, Taoism and the wide variety of ancient Greek teachings.

But in our opinion, the major reason that philosophy can be transformational is this—it’s not done in a vacuum. In the paths that use it, philosophy is integrated with other activities. When I (Greg) studied Zen many years ago, the highest teachings permeated things as mundane as holding our chopsticks while eating. Philosophy, when taught in a holistic way, transforms us though its wisdom as well through its effects on the path’s meditations, ethics and human relations.

Buddhist philosophy on emptiness offers the insight that phenomena are dependently arisen. The West has many analogous insights. Historically, we don’t mean the metaphysical teachings from Plato, Thomas Aquinas, Descartes, Kant or Hegel but what we might call the Western anti-metaphysical tradition. This is a kind of critical or counter-tradition that includes Greek skeptics, Michel de Montaigne, Pierre Bayle, Friedrich Nietzsche and, more recently, John Dewey, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Wilfrid Sellars, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Richard Rorty and Quine, as mentioned previously. There are also many others.

Modern emptiness meditations are also inspired by cognitive science, sociology, comparative religion, literature, art, film, rhetorical and cultural studies, as well as many other fields. These meditative tools give us ways to address issues quite similar to those found in Buddhist investigations, such as the self and its properties, cause and effect. There are even tools to deal with the subtle matter of what it means to hold a thesis. As Nagarjuna says about his teaching, “If I had a thesis, that fault would apply to me. But I do not have any thesis, so there is indeed no fault for me.” [5.]

Nagarjuna with Thirty of the Eighty-four Mahasiddhas.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Using the meditations

The idea behind emptiness meditations is to refute an object we think exists but doesn’t. The object can be an inherent self or something else we imagine to exist in an unchanging or mind-independent way. Although the independent object doesn’t exist, our distorted thoughts and feelings treat it as if it does. When we realize the non-existence or nonsensicality of the imagined object, the distorted thoughts and feelings fade away. Greater peace, happiness and love ensue.

For example, I might think that I really exist. After all, René Descartes said so. So I might have a conception of this self as a separate soul, a set of values, unique habits or memories. We’ve heard people say, “I can’t help it. That’s what I do. Deep inside of me, it’s who I am.” Because I have this exaggerated notion of myself, I’ll suffer when something challenges it.

So in my meditation, I’ll try to refute it. I’ll look for this separate, definable self everywhere I can. I’ll look amongst the bodily and mental phenomena. I’ll also look apart from these phenomena, such as in various religious or philosophical teachings, Platonic heavens and anywhere else I feel it could be. I’ll attempt to cover all possibilities. What will I find? Claims, beliefs, concepts, feelings, sensations, habits and actions. But I won’t find a self.

Because I’ve set up my meditation to include every possibility, I will sooner or later realize that such an independent self is unfindable and unnecessary [6.]. In fact, the closer I look, the more I don’t find it. All I find is its absence.

In the emptiness teachings, this non-finding is considered to be my realization of the emptiness of the self.

What is left? Not the self I thought existed but a contingent conglomeration called “the self”. This is a more open-textured version of the self, free to change. It depends on earth, air, water, food, biology and conceptual labelling. It’s this empty self that goes to the store, pays bills and realizes emptiness. This empty self becomes lighter, freer, kinder and happier because of these meditations.

Many emptiness meditations have these same features in common: identify the target of refutation, look systematically for it and fail to find it. They result in freedom from essentialism (belief in inherence) and nihilism. The heart expands and the web of life becomes more colourful, interrelated and immediate. In Buddhism, this web of life, permeated with our understanding of emptiness, is often called “conventional truth”. Emptiness itself is called “ultimate truth”. And even though “ultimate”, it is nevertheless empty.

We’ll now take a look at three Western approaches to emptiness meditation: ancient Greek Scepticism, Linguistic Holism and Social Construction. They each approach emptiness in a different way. Greek Scepticism works with beliefs; Linguistic Holism works with language and reference; and Social Construction works with the co-creation of meaning.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

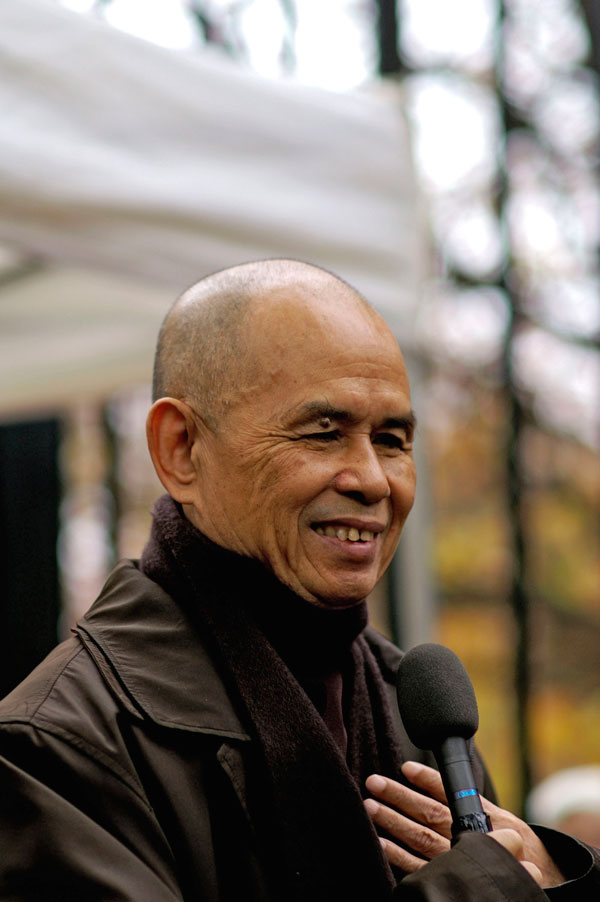

Ancient Greek Scepticism

The branch of ancient Greek Scepticism called “Pyrrhonism” [7.] is perhaps the easiest Western approach to put into practice. The key idea is that in matters pertaining to belief and truth you withhold assent as to how things really are in themselves. This leads to peace of mind, whereas being dogmatic and having beliefs about the nature of things in themselves leads to unease.

The most prolific spokesperson for Pyrrhonism was Sextus Empiricus, who lived in the second century BCE. About the consequences of beliefs in the natures of things, he wrote:

… [T]he person who entertains the opinion that anything is by nature good or bad is continually upset. When he does not possess the things that seem to be good, he thinks he is being tormented by things that are by nature bad, and he chases after the things he supposes to be good; then, when he gets these, he falls into still more torments because of irrational and immoderate exultation, and, fearing any change, he does absolutely everything in order not to lose the things that seem to him good [8.].

Sextus identifies our beliefs as chief causes of suffering. For Sextus, a belief has a greater degree of investment than a mere inclination. A belief is more like a position about things in themselves. It’s a position that one feels committed to defending against opposition. Sextus considers it to be a form of dogmatism to hold beliefs in this sense. For Sextus, even “The honey is sweet” voices a belief. It makes a claim about the mind-independent nature of honey. But “The honey appears sweet to me” is only an impression or a report on appearances.

For the Pyrrhonist, it is possible to live without having commitments about how things exist in themselves. At first, this seems impossible. “How can we even cross the street without beliefs? Don’t we need to believe that it is safe?” No, we don’t need to believe that it is safe. We can simply respond to the appearance of safety without believing that it is true of an independent reality.

Even without beliefs in this sense, the Pyrrhonist is not beset by nihilism or stupefying inactivity. Sextus himself was quite active—he was a physician, philosopher and writer. According to Sextus, one lives according to the “ordinary regimen of life”. This is strikingly similar to the Buddhist notion of conventional truth.

The Pyrrhonist is also saved from nihilism by not forming contrary beliefs. There are other varieties of scepticism that argue that “Things are not as they seem” or “Our beliefs are not accurate”. Sextus considers these statements to be expressions of “negative dogmatism” because they are also beliefs about the nature of things.

Sextus is keenly aware of the dangers of self-reference and self-contradiction with this kind of philosophy. But he manages to avoid negative dogmatism. Like Nagarjuna, he explains how he avoids self-cancellation. At many points he reminds us, “I say all these things without belief.”

Of course we can’t simply tell ourselves to stop believing. Towards this end, Pyrrhonism provides an entire arsenal of techniques called “modes” that are intended to help us withhold belief. Some of the modes attune us to the variety of likes and dislikes among humans and between humans and animals. Other modes are deconstructive critiques against logic and reveal the arbitrariness of what we accept as evidence or proof.

We use the modes by playing certain appearances off against others. As a result, we are brought to an impasse where no alternative is clearly more warranted and we don’t know which one to believe. We end up withholding assent to all of the alternatives and feel at peace.

Pyrrhonism is especially helpful in the area of spiritual claims that sound like statements of objective truth. These claims can cause clinging if we believe them, so they make excellent targets of analysis. An example would be:

(C1) “Consciousness is a product of brain activity.”

We might believe this is true. We might find ourselves defending it and getting upset when others disagree. But we can also use the Pyrrhonist “Mode of Disagreement”. This is where we remind ourselves how much disagreement there is about (C1) and how there are conflicting claims with different authoritative defenders. (C1) is not uncontested. A prominent example of disagreement comes from the corpus of nondualistic spiritual teachings.

(C2) “The brain (like all reality) is made of consciousness.”

Between (C1) and (C2), experts disagree. Among the many competing claims about consciousness and the world, which one is true? Which should we believe? To get out of this impasse, the Mode of Disagreement offers immediate assistance. Faced with contrary authoritative alternatives, we simply withhold assent to them all. It’s like saying with relief, “I don’t have a horse in that race.”

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 3.0] Wikimedia Commons

Gavagais and Linguistic Holism

Linguistic Holism is another helpful approach to emptiness. It highlights our inability to map words to the world. For the Linguistic Holist, the lack of maps explains why our safari explorers couldn’t find a stable translation for “gavagai”. And even when learning our native language, we don’t consult a map or compare a word to the world. We look from a word to the holistic webwork of other words, gestures and expressions related to it. And like the Net of Jewels itself, this webwork can be endless.

In Linguistic Holism, successful communication doesn’t require maps, invariant meanings or zero ambiguity. All it needs is fluent person-to-person interaction. Holism is a pragmatic approach. It resonates with the Buddhist idea of conventional truth, where to be happy we don’t need things to be independent or objective.

Seeing meaning as empty helps us see the world as empty as well. This reduces our tendency to cling to our conceptions about the world. Since we suffer so much from attaching to solidified meanings about things, Linguistic Holism can be a major step towards reducing our suffering. It is a move towards flexibility and kindness.

Social Construction

You’ve got to be taught

To hate and fear,

You’ve got to be taught

From year to year,

It’s got to be drummed

In your dear little ear

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

—South Pacific (1958)

Social Construction is an interdisciplinary approach to knowledge and experience. It involves language, feeling, perception, cognition, evaluation, norms, standards and points of view. Social Construction seeks to show how human experience depends upon co-created understanding and the making of meaning. Like Madhyamaka Buddhism, Social Construction looks at things we feel are inherent and self-established. But when we take a close look, do we actually find these self-established things? No, we discover how they depend on other things. We discover their emptiness.

Emptiness is frequently at play in the worlds of film and literature, even in the Hollywood musical [9.]. For example, the popular film, South Pacific (1958) contains romance with deep cross-cultural complications. The racial and romantic tensions give rise to a heartfelt emptiness realization expressed in song.

A young American, Lieutenant Joe Cable, is stationed on a South Seas island during World War II. Joe falls in love with Liat, a beautiful Polynesian woman. Marriage is discussed but he can’t go ahead with it. He feels torn, unable to fully accept Liat’s Polynesian heritage.

One evening, Lieutenant Joe is talking to his friend Emile De Becque, a French expat planter living on the island. Emile tells Joe how it feels to be the victim of racial prejudice. Emile recounts how he had proposed to his American girlfriend, a nurse stationed on the same island. She turned down Emile’s proposal, feeling uncomfortable that he’d previously been married to a Polynesian woman. The American nurse said she couldn’t explain her feelings. “This is emotional,” she told Emile. “This is something that’s born in me.”

Now that Emile sees prejudice acted out by both Americans, he asks Joe, “Why do you have this feeling, you and she? I do not believe it is born in you! I do not believe it!”

“It’s not born in you,” says Joe. “It happens after you’re born.”

Because we’re in a musical, Joe sings the rest. The song, entitled “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught” became both controversial and famous in mid-century America. The final verse, like the verse quoted above, alludes to the empty, socially-constructed roots of hate and prejudice:

You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late,

Before you are six or seven or eight,

To hate all the people your relatives hate,

You’ve got to be carefully taught!

This climactic song beautifully expresses Joe’s emptiness realization. After this, he’s able to embrace his love for Liat.

Conclusion

These three Western approaches to emptiness—Pyrrhonism, Linguistic Holism and Social Construction—are powerful critiques of separation. They operate similarly to Buddhism. They all aim to liberate us from the same kind of thing—extreme notions of independence and inherent existence. The specific targets differ from teaching to teaching but what unites them all is a profound challenge to rigid thinking and feeling. All these approaches share an ability to liberate aspects of our experience.

Footnotes

- Quine, Word and Object, The MIT Press (1960)

- The most famous source for the image of Indra’s Net, though not the first, is the Buddhist Avatamsaka Sutra

- From Jay L. Garfield’s Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way

- Non-Duality Press, 2013. In this book we choose a specific Buddhist interpretation of the emptiness teachings: the Prasangika Madhyamika system, but several others could have been used as well. A very readable introduction to this Buddhist approach can be found in His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s How to See Yourself as You Really Are

- See Jan Westerhoff, The Dispeller of Disputes: Nagarjuna’s Vigrahavyavartani, p. 63

- Depending on how the meditation is locally set up, I may be justified in concluding that it doesn’t exist. The Prasangika Buddhist meditations are set up in this logically rigorous way

- After the philosopher Pyrrho, c.360–c.270 BCE, whose teaching was to withhold assent to propositions about things in themselves

- See Benson Mates’ excellent translation and commentary on Sextus’ treatise, The Skeptic Way, p. 93

- For more on the literature and emptiness, see my “Gatsby and Gestalt Shifts” also here on The Culturium