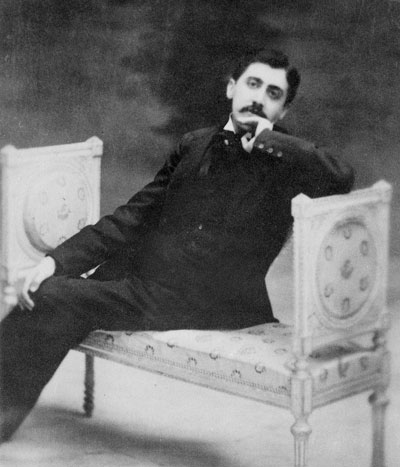

Photograph: The World’s Work,

[Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

An appreciation of spirituality and literature

Greg Goode is the author of popular books on spirituality, including Standing As Awareness, The Direct Path, Emptiness and Joyful Freedom and After Awareness. Greg is a former book critic, bibliographer and film reviewer.

A project he contributed to, Detective and Mystery Fiction: An International Bibliography of Secondary Sources, won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Greg is a member of the American Philosophical Practitioners Association and serves on the editorial board of their peer-reviewed journal, Philosophical Practice. He is currently maintains two websites, HeartofNow.com and Emptiness.co.

“… literature is a privileged ground for the realization of emptiness.”

—Jeff Humphries, Reading Emptiness

THIS IS A love letter to literature, by which I mean all art. It’s dedicated to other lovers, as well as to those who are still courting.

Paula Marvelly and I met at the first Science and Nonduality Conference a few years back in California. We hit it off right away because we shared a love of Schopenhauer, Victorian novels and the expressive arts in general. We loved the arts not only for themselves but also for their connection to spirituality. This connection between arts and spirit has been dear to my heart for many years. So I was excited to see the birth of Paula’s The Culturium blog and delighted when she invited me to contribute an article.

The subject crosses paths with a new book I’ve written, called After Awareness (due for publication in November 2016 from Non-Duality Press). In that book, I recommend a passionate engagement with the arts as an antidote to attachment and suffering. The idea is that literature and the other arts are not only inspiring and enjoyable but they also present us with new ways of seeing the world. Seeing the world in new ways helps dissolve attachments to our current views. The arts, especially the written and spoken arts, can free us from the narrow assumptions that meaning is only literal. Freedom from literality in turn helps dissolve our attachment to all images and views, including those we have about ourselves.

In this article, I would like to discuss a few ways that the arts can bring about these freedoms. Over the last month, I asked several of my friends if they’d ever had an experience with the arts that fostered lasting benefits of a spiritual kind. I left the term “spiritual” open to their own interpretation. Their replies were fascinating and instructive.

On reading Jane Austen:

Her work has made it more interesting and deeper to see different sides. Along with that comes more acceptance, compassion for my own views, which change of course.

On reading Eric Frank Russell:

From that day I knew that my thoughts were free and my inner world was free—that there were possibilities and different ways of being in the world.

On listening to Mozart’s Great Mass in C Minor:

There was a sense of catharsis, a feeling that many tensions I hadn’t even known about were relieved … Which translated to less reactive behaviour and thoughts and feelings, more compassion, patience, goodwill, empathy, generosity, forgiveness.

On watching Richard Linklater’s Waking Life:

[It] implanted in me a questioning of accepted, common sense reality.

On writing:

… my experience has been that writing and spiritual investigation can be beautifully, and naturally, inter-fluent.

Of course, not everyone may feel the pull of the arts. I have several friends who follow science research as an adjunct to spiritual growth. They don’t happen to share my love of the arts. But it’s my experience that heartfelt participation can bear spiritual fruits. We can write, paint, compose, dance or sculpt. Or we can play the role of reflective readers, listeners or viewers, experiencing the aesthetic work of others.

But isn’t this too obvious to mention? Haven’t our schoolteachers told us over and over that “reading is good for you” and “art will expand your horizons”? Yes, but sometimes in spiritual contexts, we hear the opposite message. The message sounds authoritative and can carry a lot of weight. Several decades ago, I attended Christian churches that taught against reading any books besides the Bible and Strong’s Concordance. More recently, I’ve heard teachers involved in Eastern paths say that, as one approaches enlightenment, one naturally reads fewer books, especially fiction. It’s supposed to apply to everyone and it’s supposed to be a good thing.

I never heeded these spiritual directives. I never told the church leaders that while I was a member, I also wrote as a book critic and movie reviewer. I never told satsang teachers that my briefcase contained both Sri Atmananda’s Atma Darshan (1946) and Michael Connelly’s haunting novel, The Last Coyote (1995). My love of literature was too deep to dislodge. It had come from my artist parents, who kept the house filled with books and art projects.

Photograph: Agence France-Presse,

[Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Spiritual fruits

By “spiritual” fruits, I mean transcendence or transformational insights into the ultimate nature of things. I’m using “transcendence” in a deliberately unspecific way, since I don’t wish to presume a particular concept of spirituality. I invite you to fill in these terms for yourself and see how they apply in your case. One example of transcendence would be the realization of emptiness referred to in Jeff Humphries’ epigraph at the top of this article. For Humphries and the Buddhist path he writes about, this is the realization that things have no fixed or true nature. Broad and open “naturelessness” is their nature.

In fact, Humphries, who wrote Reading Emptiness (1999) as a professor of comparative literature, was enthusiastic about the connection between spirituality and literature:

I have … concluded that the closest thing in Western culture to the Middle Way of Buddhism is not any sort of theory or philosophy but the practice of literature—reading and writing.

I would like to apply Humphries’ conclusion but allow it to be broadened. In what follows, I will use “emptiness” as a metaphor for the transcendent, “Buddhism” as a metaphor for spirituality and “literature” as a metaphor for all the creative arts. You may feel free to interpret these terms in other ways as well.

Besides transcendence, there are other qualities I’d like to count as spiritual fruits. I mean the edifying character attributes taught by spiritual traditions. These include kindness, generosity, honesty, patience, discernment, discipline, forbearance and many others. Because spiritual traditions value them and teach them, I will also consider them to be spiritual values.

How can aesthetic engagement be conducive to spirituality? In my experience, the more we read and the more we contemplate what we read, the greater the spiritual benefit. We also find spiritual benefit coming from a wider variety of literature. Our reading need not confine itself to works designated as spiritual ones.

Benefit may come through simple didactic works that encourage us to be kind, patient or courageous. Reading may take us to new worlds. As my sample pollsters mention above, the experience of new worlds increases our empathy. Reading may challenge our understanding of words and images. It may and help us become less literal and more open to poetic, figurative and literary meaning. In turn, we become more open and flexible. Or we may even experience a realization of the ultimate truth of things, however we understand it. All of these events in reading help dissolve attachments to our views of things. When our attachments dissolve, we move at least a little bit towards transcendence, towards an experience of the spacious and luminous emptiness of things.

What and how should we read? The rest of this article will discuss these questions. Must we stick to the spiritual classics? I don’t think every modern reader will be able to do so. Not everyone will be able to derive benefit from Milton’s Paradise Regained (1671), Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) or other older works. We should be able to resonate with the work and be open to having it affect us deeply.

Must we start reading in a “spiritual” frame of mind or will reading do this for us? The approaches I will discuss actually let the magic come from reading. We can read for specifically spiritual motives, such as edification or even transcendence. I will discuss these types of reading. But these motives aren’t necessary. Even without them, spiritual benefits soak in when we read with goodwill, innocence and open-mindedness. They are gifts of childhood, so we actually start out reading this way. And further reading is able to deepen these traits. As a bare minimum, I think that they are the only traits we need in order to derive spiritual benefits from reading.

I’d like to distinguish several different types of reading and the ways they interact with spirituality. Of course the possible ways of reading are infinite. But in The Role of the Reader (1979), Umberto Eco narrows them down to “naive” and “critical” reading. In The Genesis of Secrecy (1979), literary critic, Frank Kermode, distinguishes “carnal” from “spiritual” reading. These terms capture crucial differences in how we interpret texts—passively versus actively; naively versus consciously. But I’d rather not cut so coarse. It seems to me that there are more than two ways that spiritual qualities emerge from the act of reading. I will distinguish four types: reading for transcendence; didactic reading; nourishing reading; and literary reading. My “literary” corresponds to Eco’s “critical” and Kermode’s “spiritual” categories.

Reading for transcendence

Reading for transcendence is a combination of the taste for transcendence on our part and a work that points to the transcendent. Our taste for transcendence is a yearning to experience the ultimate through the work of art. Some works point fairly directly to transcendence. These are the kinds of works that The Culturium is already documenting, with articles on Jordan Belson, Paul Cézanne, Jean Cocteau, E. M. Forster, Alice Koller, Andrew Marvell, Alain Resnais, J. D. Salinger, Rabindranath Tagore and others. The site’s guiding theme is to present:

… writers, filmmakers, artists, performers, musicians, philosophers, sages and poets who have delved deep into the silence within and created work that is timeless, wise and beautiful.

The site’s articles serve up samplings of transcendence. We are presented with expressions of eternity, wisdom and beauty. The Culturium is one of my favorite sites. I’d love to see more of its kind. When I read these articles, I feel inspired to write for the site or maybe even create a similar site of my own!

Reading for transcendence also includes lectio divina, which is a devotional, contemplative reading enlivened by faith. Lectio divina was inspired by Origen in the third century and systematized in a twelfth-century work called A Ladder of Foure Ronges (1150). The ladder is a way of reading scripture that conveys our questions to God and God’s answers to us. The four rungs of the ladder are reading, meditation, prayer and contemplation:

Reading puts as it were whole food into your mouth; meditation chews it and breaks it down; prayer finds its savour; contemplation is the sweetness that so delights and strengthens.

Although lectio divina is a powerful route to transcendence, it is a Christian tradition. But it can take place in other ways too, as we become less literal and more figurative in our approach to language. The more comfortable we are with figurative language, the more creative we can be with terms such as “God” and “faith”. With greater creativity, we can approach a wider variety of works in a devotional way.

Reading for transcendence may include our reading of spiritual autobiographies such as Saint Augustine’s Confessions (397–400 C.E.) or spiritually edifying Bildungsroman stories like Goethe’s Faust (Part One, 1806; Part Two, 1831) or A Romance of Two Worlds (1886) by Marie Corelli. There is a strong overlap between reading literature for transcendence, reading for story and reading for spiritual, edifying information. These books may fit into several categories. Reading for story and nourishment, as well as reading for didactic reasons are discussed below.

Reading for transcendence is a mature, even rarified reason to read. The works tend to have transcendence as a theme and they’re generally sophisticated or metaphysical. But there’s another category of spiritual reading that doesn’t require such mature motivation. It comes earlier in our life as readers. I’ll call this “didactic” reading. It’s didactic not necessarily because we desire to be instructed or edified but rather because the works themselves are composed for purposes of edification.

Photograph: Bain News Service, Library of Congress,

[Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Didactic reading

Didactic reading usually requires the work to be didactic. Such works would include most books written for children, as well as the enormous body of literature that contains explicit moral or religious messages. Didactic literature includes traditional folklore, fables and mythology, monotheistic parables, Buddhist Jataka stories and Hindu Puranas. In children’s books and fables especially, the moral teaching is right on the surface of the text.

From A. A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh (1926):

Promise me you’ll remember, you are braver than you believe, stronger than you seem, smarter than you think.

From Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince (1943):

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

From Aesop’s Fables (620 and 560 BCE), “The Lion and the Mouse”:

No act of kindness, no matter how small, is ever wasted.

These are examples of didactic literature at its simplest. But I think didactic literature can also include books for mature readers. For adults, the messages are often social or political and we often read these works for the message as well as the story. Classic utopian visions such as Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) and Austin Tappan Wright’s Islandia (1942) carry a positive message and an exciting plot. Of course utopian stories suggest their own shadow side and there are plenty of grim, dystopian novels that are even more fun to read, such as Jack London’s The Iron Heel (1908), Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (1921), Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). The edifying lesson of the dystopian works is not that that their bleak, repressive societies are inevitable. It is precisely the opposite—that we should work to prevent them.

Another didactic category deals with slavery and includes both slave narratives and abolitionist fiction. Well known narratives include Solomon Northrup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853), which became an award-winning film in 2013, and Olaudah Equiano’s earlier work, The Interesting Narrative and the Life of “Olaudah Equiano” or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789). The most influential abolitionist novel is certainly Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). It became the nineteenth-century’s best-selling novel and proved instrumental to the abolitionist cause in the United States.

Didactic reading may be done with the motive of spiritual development. But even if we read didactic works for pleasure, it’s hard to escape the edifying message. This is because the message is so plain and easy to discern. Didactic works are concrete and pragmatic, focussing more closely on ethical themes and less on full spiritual transcendence.

But spiritual benefit can also come from reading that isn’t meant to be transcendent or didactic at all, as we’ll see in the next section.

Nourishing reading

I would urge that the novels of Proust and James help us achieve spiritual growth and thereby help many of us do what devotional reading helped our ancestors do.

—Richard Rorty quoted in Christopher J. Voparil and Richard J. Bernstein (eds.),

The Rorty Reader

What if we’re reading for pleasure or nourishment? Can there still be spiritual benefits when we don’t read for expressly spiritual purposes? Even when the works aren’t didactic or transcendent?

Yes and yes. In fact, this category of reading opens the door to the entire world of creative expression. The scope is virtually limitless. We actually don’t need spiritual content or spiritual motives in order to derive spiritual benefit from the act of reading. All we need are goodwill, innocence and open-mindedness, as I mentioned above. These qualities are themselves spiritual traits. They will harmonize with the qualities in the work, as well as those in the act of reading itself.

So maybe reading is good for us. Of course because teachers drum this into us, it sounds corny, uncool and probably false. Who wants to read for that reason! It may sound better coming from modern psychologists. In June 2013, Time Magazine published an article entitled, “Reading Literature Makes Us Smarter and Nicer”:

Raymond Mar, a psychologist at York University in Canada, and Keith Oatley, a professor emeritus of cognitive psychology at the University of Toronto, reported in studies published in 2006 and 2009 that individuals who often read fiction appear to be better able to understand other people, empathize with them and view the world from their perspective.

Because the list of attributes I’m associating with spirituality is pretty broad, “smarter” and “nicer” are included. To develop greater discernment is being smarter and to develop greater empathy and compassion is being nicer.

Mars and the African jungle

Reading fiction can nurture us with courage and inspiration. The website called The John Carter Files collects quotes on Edgar Rice Burroughs (author of the John Carter and Tarzan books) from “those who have shaped the world, science and pop culture”.

From Ray Bradbury:

I’ve talked to more biochemists and more astronomers and technologists in various fields, who, when they were ten years old, fell in love with John Carter and Tarzan and decided to become something romantic. Burroughs put us on the moon.

—Listen to the Echoes (2010)

From James Cameron:

My inspiration is every single science fiction book I read as a kid. And a few that weren’t science fiction. The Edgar Rice Burroughs books, H. Rider Haggard—the manly, jungle adventure writers. I wanted to do an old-fashioned jungle adventure, just set it on another planet.

[Regarding Avatar]

From Carl Sagan:

The Mars novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs … aroused generations of eight-year-olds, myself among them, to consider the exploration of the planets as a real possibility.

—Cosmos (1980)

Bradbury, Cameron and Sagan are referring to Burroughs’ twenty-four Tarzan books and the eleven John Carter stories, especially A Princess of Mars and John Carter of Mars. I regard the inspiration felt by these men as spiritual, even though the works are not devoted to spiritual topics.

I can relate. My own childhood heroes were Socrates, Sherlock Holmes, James Bond and Napoleon Solo from the 1960s’ Man from U.N.C.L.E. television show. I remember one year in grade school when I had a hard time with mathematics. I liked Napoleon Solo more than his partner, Illya Kuryakin, and for some reason I felt that Solo was very good at maths. I was inspired by how he handled all his difficulties with effortless aplomb. Immersing myself in the show every week inspired me. It gave me courage. It even made me feel smarter and more capable! When I began to tap into this inspiration, my maths difficulties went away, never to return.

In her fascinating book, Gothicka: Vampire Heroes, Human Gods and the New Supernatural (2012), Victoria Nelson discusses various cases in which fiction has a particularly transformational effect. She reports on the readers of J. R. R. Tolkein, Anne Rice, Stephenie Meyer and the fans of zombie books and movies. In each case, these readers have participated in what Tolkein calls a “Secondary World”. For Tolkien, this world is the result of “story-making in its primary and most potent mode”. The Secondary World can summon a response that he calls “Secondary Belief”, which is our feeling of assent and attraction to this world. For our fans of Middle Earth, vampires and zombies, the Secondary World becomes spiritually nourishing through reading, social interaction, websites, conventions, role play and fan fiction.

Nelson looks at these activities as new forms of spirituality. They are reminiscent of the Christian mystery plays that were performed at religious festivals in the Middle Ages. The mystery plays would represent stories from the Bible, such as the creation of the world or the resurrection of Jesus from the grave.

Ted Tschopp of Tolkein Online explains the Secondary Belief phenomenon:

People want to participate in the universe they love … A hundred years ago people all went to church. Even if they didn’t believe it, they bought into the overarching story that was involved. Today there is no meta-story. One reason people like Tolkien is because they want a myth that’s true and they see it there.

For at least some readers of Tolkein, Rice and Meyers, the novels have inspired an edifying form of spirituality.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Proust, James, Austen and zombies

Richard Rorty, a famous American philosopher whose interests turned towards literature at the end of his career, recommended the novels of Proust and James for spiritual growth. But here I’m giving equal credit to books featuring Martian queens, apemen, hobbits, elves, wizards, vampires and werewolves. Aren’t the two sets of books on opposite ends of the cultural spectrum? Isn’t there a crucial highbrow/lowbrow difference? For example, academia in the United States has always considered Proust and James respectable but didn’t sanction research into popular literature until the early 1970s. But as time goes by, the idea of a strict cultural divide seems to be taken less seriously. Some critics, such as Perry Meisel in The Myth of Popular Culture: From Dante to Dylan (2006) argue that there is no sound basis for the distinction in the first place. Case in point—in the first quarter of 2016, the movie Pride and Prejudice and Zombies is due to be released, adapted from Seth Grahame-Smith’s 2009 otherworldly mashup of Jane Austen’s classic 1813 novel. I saw the trailer and it looks fun!

Fortunately, we do not need to decide these cultural and canonical issues. For my purposes, any work of artistic expression that can inspire spiritual benefits is worthy of consideration.

When we read novels or watch movies in a nourishing way, we immerse ourselves in the worlds they present. We may even become Tolkeinian “Secondary Believers”. When the new world is vivid, convincing and memorable, it captures us within. We don’t even need to suspend disbelief because the process is spontaneous. The distinction between reader and work melts away.

The experience of being immersed in a fictional world provides several kinds of spiritual fruits. One, the distinction between self and the work of art dissolves into a nondual unity. Two, the work opens our mind towards possibilities that are new to us. This leads to greater acceptance and empathy, which were actually qualities mentioned by my friends in the informal survey I mentioned earlier in this article. Three, it dissolves attachment. The fact of getting caught up in the fictional world weakens the unspoken assumption that our everyday world is the only possibility there is. Over time and with more reading, our everyday world may become more like a creation, even if we don’t contemplate the issue. The plausibility of each particular world helps reduce our certainty about the “reality” of others. None of the worlds is invalidated. Rather, all of them are transformed.

And finally, there may even be some moments in which we experience the exquisite beauty of transcendence itself. When we read literature and experience the wonder and appeal of other worlds, there may be a flash in which we consciously recognize the delicacy or emptiness of our current world. That is, we may have the strong intuition that our world is not grounded on anything fixed or absolute. This realization, if conscious, may be destabilizing at first, but it catapults us to the transcendent. In that beautiful moment, we have nothing to say or think about all this. It is beyond all words and concepts.

Even if this experience of transcendence is over in a flash, the after-effects remain. We begin to experience everything about the everyday world as lighter, freer, more creative and more spacious.

From world to world

The Ambassadors (1903) by Henry James dramatizes a realization of precisely this type, where a new world helps dissolve our attachment to an old one. Lambert Strether is a passive (Lamb-bert), sheltered, middle-aged man living in Woollett, Massachusetts. Strether’s fiancée, the wealthy widow Mrs. Newsome, tasks him to travel to Paris to find her son, Chad Newsome, and bring him back to Woollett. Chad may have become involved with an inappropriate woman and should be brought home. Strether goes to Paris, and while there sees how polished, confident and capable Chad has become. The people around Chad are similar. Strether tastes this greater freedom and sophistication for himself and comes to see his former life in Woollett as wasted.

At one point, Strether verbalizes his realization. He tells Little Bilham, a starving-artist friend of Chad’s:

This place and these impressions … of Chad and of people I’ve seen at his place—well, have had their abundant message for me … [T]he right time now is yours. The right time is any time that one is still so lucky as to have … Don’t, at any rate, miss things out of stupidity … Live!

Because the entire novel is narrated from Strether’s point of view, we as readers get to experience his realization on two levels. We understand that Strether is a person in the novel undergoing this shift. And we also get to experience the shift for ourselves, through Strether’s eyes.

To transcendence

One of most poignant and enlightening examples of transcendence I recall is enacted in Life on a String (1991), a Chinese film by Chen Kaige. Based on the novel by Shi Tiesheng, it tells the story of a blind banjo player. As a young boy, he is told by his master that if he plays the banjo for many years, he will eventually break a thousand strings. When he breaks the thousandth string, he will find a script that will allow his sight to be restored.

He travels the countryside, adopts his own blind student and continues playing until he reaches old age. Now an old master, he finally breaks the thousandth string and is utterly shocked by what happens. His surprise induces a profound realization, which is enacted through the final song performed at a night-time mountaintop gathering. Director Kaige dramatizes this moment though serene camera movements, uncanny medieval lighting, and the resolute singing and facial expressions of the leathery old banjo master. Through the epic meaning and surreal beauty of the song, we share the master’s realization and can ourselves experience transcendence. It’s one of the great spiritual films in world cinema. I cry tears of joy every time I see it.

Literary reading

The kind of reading I’m calling “literary” is sometimes called “critical” or “deep” reading. It builds on all the kinds of reading we’ve discussed so far. It also includes reflection and analysis about the work we’re reading. It may include reading about the work we’re reading. With literary reading, we become attuned to the multiplicity of meaning in a work. We become able to see the work itself in different ways, which broadens our understanding of it and gives us different perspectives on ourselves as well.

Literary reading brings attention to the various types of non-literal meaning that a work can have, including figurative, rhetorical and performative meaning. We may look into the work’s historical and social context, as well as its relationship to other works. We proceed with a great deal of self-awareness about our own procedures as we engage the work. This self-awareness is a valuable part of the literary approach. It provides flexibility and at the same time it keeps us from taking ourselves too seriously.

Looking through versus at

With didactic, transcendental and nourishing reading, we are moved and influenced by the words on the page. We experience the sensations and perceptions described in the text. We react to the figurative language. We feel the poetry. We are taken through the words to the world beyond. For example, when we read The Great Gatsby in a nourishing way, we enter the 1920s’ world of upper-crust New York society. We feel Gatsby’s dreamy, romantic yearning as he looks at the green light across the bay on Daisy Buchanan’s dock.

But with literary reading, we look at the words as well. In the Gatsby case, we might contemplate the famous symbol of the green light, which seems to represent hope and the future. Perhaps, following hints in the book, we think about the green light in affinity with the wider concepts of the future and the past. These concepts can shed light on the narrator’s observation on the last page, in which he says that Gatsby’s dream:

… was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

We may come to see the green light as pointing not to Gatsby’s dream of the future but beyond it, all the way to “that vast obscurity”, which can be identified with emptiness itself. This would be an example where literary reading leads us to a realization of transcendence, which hadn’t happened in our nourishing reading of the book.

When we read a work, we often have an interpretation that seems most obvious to us. But if we have the chance to witness our obvious view being edged out by a different, perhaps more encompassing view, we are again taken to that transcendent place beyond words or concepts. For a little while at least, we are without answers, without grounding. We emerge from the moment with a greater appreciation of the fragile beauty of meaning itself. This experience helps us realize the fragility of our views in general. In turn, this opens the heart and the mind.

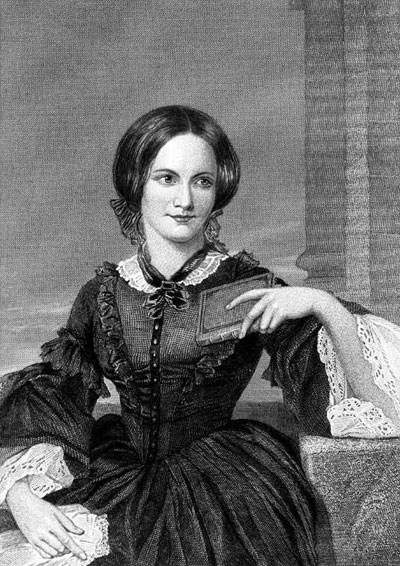

George Richmond, Charlotte Bronte.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

My point is not that we will discover the “truth” of the work in one of these readings. My point is that alternate readings are there to explore. Even if we don’t take the opportunity to explore them, their mere presence indicates the delicate and precious openness and emptiness of meaning, the lack of any inherent, final meaning standing on its own. When we experience deeply that our favorite interpretation isn’t objectively grounded, our very lack of certainty is a taste of the transcendent. It’s a powerful spiritual insight, all the more powerful when we love the work.

The conversation

Sometimes a work can even lead us to realize the emptiness of the act of reading itself. Various cases of the “unreliable narrator” in fiction draw attention to the possible falsehood of any act of narration and by extension, the very act of reading. Well known unreliable narrators include Nelly Dean in Wuthering Heights (who elevates her importance to events), Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby (who contradicts himself and omits facts) and Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye (who lies). But perhaps the pre-eminent unreliable narrator in fiction is Dr. James Sheppard in Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. The book begins like a classic whodunit. But it ends with one of the most radical plot twists imaginable: the narrator himself is revealed to be the murderer. This is narrative unreliability of an extreme, unexpected kind. It illustrates how easy it is for any statement to deviate from the what we ordinarily take to be the truth.

Sometimes a work affects us deeply. I was an avid movie buff even as a young man and saw Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation during its initial release in 1974. Watching it, I had the surreal experience of doubting the evidence of my ears, my memory and my ability to interpret sound. I think the whole 1970s era contributed to my moments of unease as I was watching the film. The film appeared shortly before President Nixon resigned, at a time when the Watergate break-in was still in the air and teenagers were being drafted and sent to Vietnam. People in the U. S. were already distrustful and cynical.

In the film, Gene Hackman plays Harry Caul, reputedly one of the best freelance wiretappers in the business. He is hired by a prominent corporate exec (Robert Duvall) to record the conversation of a skittish young couple (Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) as they walk around San Francisco’s Union Square. They realize they may be followed, so they speak quietly and in code.

Afterwards, Harry spends hours post-processing the audio. At one point, it becomes clear that Frederic Forrest says, “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” Harry listens to this phrase over and over but it always comes out the same. “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” Harry is a strict Catholic and is now presented with a moral dilemma. Should he report this? It only seems right but his professional code of ethics requires that he never get involved in the content of his recordings.

Harry begins to shadow the couple, to protect them from harm. One day they have a meeting in a hotel room. Harry listens through the wall from next door and hears screams, bangs and muffled sounds of violence. The next day it turns out that Robert Duvall has been murdered and the couple is alive.

Harry is shocked! Feeling depressed and disoriented, he replays the tape in his mind. He hears it in what seems to be a new way, “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” The tiny change in emphasis turns the entire story around.

Sitting in the theatre back in 1974, I was speechless but fascinated at the same time. Had I misheard the audio? Was I misremembering? Had my comprehension been influenced by the story’s context? Had it actually been spoken two different ways? What was really going on? Those were pre-VHS days, so I couldn’t rewind. Any of these theories seemed plausible. I watched the film several times over the years. Each viewing clarified things a bit but still took me to a delicious, puzzling and mystifying place.

During the preparation of this article, I carefully watched a recorded version of the film. The phrase is actually spoken in two ways. The first time occurs at 00:38:50 and the emphasis is on “kill”. Later, at 1:45:37, the emphasis is on “us”. The words are right next to each other and the new emphasis has the opposing meaning.

To some extent, the mystery is Harry’s own character issue, as well as our perceptual problem. Harry is his own kind of unreliable witness. He is not as perceptive as his reputation suggests. Coppola limns Harry’s character in a brilliant cinematic way through visual metaphors on Harry’s surname “Caul”, which also refers to a translucent net or veil that covers something. Harry is usually shown wearing a translucent plastic raincoat over his suit and some of his longer speeches in the film are delivered as he’s actually standing behind plastic sheets or partitions.

“He’d kill us if he got the chance.” What a difference a bit of emphasis can make! What a frail thing the sentence! In my speechless moments back in 1974, I had no supports for the meaning. It was another case of being taken to the vastness beyond words and concepts. The movie allowed me to experience the vulnerability of perception and cognition. And I gained a lasting appreciation for the genius of art to convey this thrilling wisdom.

Conclusion

Literature and spirituality can be practised apart or together. My own preference is together and I like how The Culturium documents the beauties of this path. Even though I discuss various points of contact between the two endeavours, I don’t mean to recommend that people doing just one of them should rush out to the library or YouTube and take up the other. Each pursuit is fine by itself. But if you do happen to be practising both, then what happens if they are allowed to talk to each other? Something magical may happen!

Post Notes

- Greg Goode’s Amazon page

- Greg Goode’s website

- Greg Goode & Tomas Sander: Joyful Freedom on The Culturium

- Greg Goode: Colin Turbayne and the Myth of Metaphor on The Culturium

- Jeff Humphries, Reading Emptiness: Buddhism and Literature

- Umberto Eco, The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts

- Frank Kermode, The Genesis of Secrecy: On the Interpretation of Narrative

- Annie Murphy Paul, “Reading Literature Makes Us Smarter and Nicer,” Time Magazine, 3rd June 2013

- Christopher J. Voparil and Richard J. Bernstein (eds.), The Rorty Reader

- The John Carter Files: John Carter, LEGEND OF TARZAN, and all things Burroughs

- Victoria Nelson, Gothicka: Vampire Heroes, Human Gods and the New Supernatural

- Ted Tschopp of The One Ring: Tolkein Online, quoted in Eric Davis, “The Fellowship of the Ring,” Wired, October 2001

- The One Ring: Tolkein Online

- Perry Meisel, The Myth of Popular Culture: From Dante to Dylan

- Origen (185–253 C.E.) sets forth the importance of prayerful reading in his Letter to St. Gregory Thaumaturgus. Later, in about the year 1150 C.E., Gugio II, the Carthusuan wrote what has become known in English as the The Ladder of Monks or A Ladder of Foure Ronges, which describes the four rungs as reading, reflection, prayer and restful openness. The quote is from the First Chapter.

- Variant interpretations of Jane Eyre, feminist, Marxist, psychoanalytic and postcolonial. An early feminist interpretation is given in Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. A prominent Marxist interpretation is given in Terry Eagleton’s Myths of Power: A Marxist Study of the Brontës. A psychoanalytic perspective can be found in Dianne F. Sadoff, “The Father, Castration and Female Fantasy in Jane Eyre” in Jane Eyre, ed. Beth Newman. And a well known source for the postcolonial interpretation is “Three Women’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism” by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Critical Inquiry, 12:1 (Autumn 1985).