Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

How language opens to the divine

“The main theme of this book is that we should constantly try to be aware of the presence of metaphor, avoiding being victimized by our own as well as by others.”

Colin M. Turbayne

Greg Goode is the author of popular books on spirituality, including Standing As Awareness, The Direct Path, Emptiness and Joyful Freedom and After Awareness. Greg is a former book critic, bibliographer and film reviewer.

In The Culturium’s latest guest post, Greg explores how our language, thought processes and even apperception of the entire universe itself can be veiled under metaphorical conceits. In this brilliant essay, he examines the work of his college professor, Colin Turbayne, and his thesis on the perils of allegory and mythology, finding ultimately that truth lies beyond the realm of words.

THE MYTH OF METAPHOR (1962) [1.] is a subtle work, even subversive. It reads like a bland book on language but it poses a devastating challenge to the idea of literal, objective truth. In this way Turbayne’s challenge is similar to Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction, which first appeared in France a few years later. But whereas Derrida often wrote with fanfare and messianism, Turbayne’s style is avuncular, genial and low-key. Reading his book is like having afternoon tea with a tweedy, soft-spoken college professor.

Turbayne’s low-key assault on objectivity opens up a nonconceptual space reminiscent of the Buddhist “emptiness of emptiness”. This is the insight that the teachings are able to help free us from all conceptualization, including their own. In short, the emptiness teachings are also empty. Turbayne’s enquiry into metaphor does the same thing. It frees us from being deceived by metaphor and at the same time refuses to see itself as an objective account of reality.

I find it inspiring that for Turbayne, this nonconceptual space leaves room for divinity, which is usually prohibited by the academic philosophy market. But by the end of the book, he has indeed embraced divinity but in a gentle, personal way that doesn’t obligate anyone else to follow suit.

Professor Turbayne and Berkeley

Colin M. Turbayne (1916–2006) really was a tweedy college professor. He was one of the world’s eminent scholars of George Berkeley (1685–1753). And he actually wore brown tweed sport coats on campus. I was fortunate enough to attend his Berkeley class in the mid 1980s.

As a Berkeley teacher, Turbayne had the nearly impossible job of clarifying Berkeley’s anti-materialist philosophy to astute twentieth-century college students, most of whom were scientific materialists. Berkeley argued against the notion of material substance, which was usually characterized as a kind of external, all-purpose physical stuff.

According to the materialistic philosophies of Berkeley’s opponents, material substance is the main ingredient in the world. Supposedly it makes up everything in the physical world, while also serving as the cause or our perceptions.

In philosophical disquisitions … we ought to abstract from our senses and consider things themselves, distinct from what are only sensible measures of them.

—Isaac Newton

Berkeley’s opponents held that material substance takes on a variety of specific qualities, depending on the situation. For example, when manifesting as a chair, material substance will exhibit the qualities that include a chairlike colour, shape, size, position and degree of movement or rest. Against this, Berkeley argued that the very idea of physical substance makes no sense.

Turbayne knew that teaching Berkeley’s critique would be difficult because materialism in its various incarnations has been our default view for generations. So he used a trick in class. To get us to study harder, he sought to leverage our desires for good grades. During our very first class meeting he announced our final paper, which would count for something like 30% of our total grade in the class. He said:

I know that Berkeley’s arguments are out of the ordinary. In your paper, you may decide to write in favour of them or against them. But please be aware that if you write against Berkeley, your paper will have to be much better to earn an “A” than if you write in favour. This is because he has truth on his side.

—Colin Turbayne

More profound than idealism

Turbayne was passionate about getting us to understand Berkeley’s arguments and his trick did work with me. But at the time, I noticed something strange. I never saw Turbayne present Berkeley as a metaphysical idealist, one who holds that only ideas (and perhaps minds) exist. I had joined the class ready to hear about Berkeley’s idealism.

But Turbayne just didn’t go there. In fact, he hinted a few times that Berkeley had a more profound philosophy that wasn’t related to idealism at all. Turbayne frustrated us by never providing any more detail. When we asked, he’d just drop more hints, look at us with a gleam in his eye, and recommend a book of his own, The Myth of Metaphor. It wasn’t one of the texts for the class, perhaps because it was about language, not Berkeley.

But after reading this book and Turbayne’s other writings over the years, I came to understand what he meant. Throughout his career, Turbayne probably wrote as much about metaphor as about Berkeley. This may explain why Turbayne’s Berkeley emerges as a philosopher of language, not an idealist metaphysician. Turbayne even gave a name to his approach, “the metaphorical way” [2.]. He considered it more profound than idealism because idealism (like materialism) lands us in a trap that the metaphoric way frees us from.

And what is the trap? Being victimized by metaphor.

Turbayne’s strategy

Turbayne’s strategy gets us to cultivate an awareness of metaphor. With this awareness, we won’t be victimized.

To be victimized by a metaphor is to take it literally, as an account of the objective truth. We are victimized if we take a metaphor as fact, instead of seeing it as figurative language.

Oddly enough, Turbayne never tells us exactly why it’s so bad to take metaphors literally. The most he says in The Myth of Metaphor is that when we take a metaphor literally, we are making a kind of intellectual mistake. He also hints that when we don’t make this mistake, we enjoy a kind of freedom that, among other things, opens to the divine. I’ll return to this issue below.

Turbayne doesn’t discuss this freedom explicitly. And it’s understandable—The Myth of Metaphor is a sober academic work on the philosophy of language. So Turbayne edges into this freedom in a roundabout way. His prose style is sometimes frustratingly indirect. The book looks tightly organized in the no-nonsense Anglo-American philosophical style. It has clearly titled chapters and subheadings, along with a table of contents and index. But the main argument remains partially hidden. You almost have to read the entire book several times and then stand back and put it into deep focus.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

- Present an account of how language and metaphor work.

- Show how to recognize metaphor, especially in scientific discourse.

- Try to remove the metaphor and get to the literal truth.

- Discover that we cannot get to the literal truth.

- Return to the same metaphor or a new one but this time with awareness.

- Expose Descartes and Newton’s scientific theory as only a metaphor (“the world is a machine and vision happens via geometry”).

- Provide an alternate metaphor (“the world is a universal language and so is vision”).

- Clarify that since these are only metaphors, neither one can validly claim to be the objectively correct description of the world.

- Test the language metaphor against some classic scientific paradoxes to see how it accounts for our observations.

- Conclude that the language metaphor accounts for the facts at least as well as the machine metaphor.

- Support this conclusion by adding that the language metaphor leaves room for the divine, whereas the machine metaphor does not.

I will focus on Turbayne’s notion of metaphor and approach to language, and then move on to his suggestions for becoming free of taking the metaphors literally. I will conclude with a brief sketch of what this freedom looks like. Unfortunately, there isn’t enough space here to cover Turbayne’s presentation of his language metaphor or the shootout he stages between his metaphor and the machine metaphor.

Defining metaphor

Turbayne defines metaphor as “the presentation of the facts of one category in the idioms appropriate to another”. He sometimes refers to categories as “sorts” and metaphor as “sort-crossing”[3.]. Using metaphors, we cross sorts between categories, including mental, nautical, architectural, geometrical, metallurgical and many more. For Turbayne, using metaphor:

… involves the pretense that something is the case when it is not … Descartes pretended that the mind in its body was the pilot of a ship; Locke that it was a room, empty at birth but full of furniture later; and Hume that it was a theater … Optical theorists have pretended that we see by geometry. Metal experts present the facts about metals that break after constant use as if they suffer fatigue, while physicists make believe at some times that light moves in waves, at others that it consists of corpuscles, in order to account for different observable facts in the motion of light.

—Colin Turbayne

Metaphor is often discussed as a rhetorical trope, a specific kind of figurative language. In the reference guides of rhetorical scholars you can find hundreds of tropes. Many of them are similar to metaphor, including metonymy, synecdoche, metalepsis and allegory. But Turbayne’s analysis doesn’t depend on the differences between them. In a sense, “metaphor” becomes a metaphor for figurative language in general. Turbayne’s primary focus is the ability of meaning to depart from the literal.

Turbayne gives many examples of metaphor:

- Man is a wolf

- Mussolini is a utensil

- An iron curtain has descended across the Continent

- Sound is vibration

- Gravity is a vital force

- I see the point of the joke

- I grasp the meaning

- He boasted from vanity

- God is the greatest architect

Some of these examples are more obviously metaphorical than others. There is a different degree of make-believe involved. “Man is a wolf” is pretty obvious. We’re alluding to certain wolflike characteristics and we apply them to man. We probably don’t pretend that man really is a wolf. But “I grasp the meaning” is a little less obvious. We may visualize the mind reaching out and taking hold of meaning. We may pretend that grasping happens like this but if we’re asked, we’d probably say that we don’t take it literally.

But with “sound is vibration” we may take it literally. We may think that sound really is vibration. Turbayne would say that in this case, we don’t make-believe, we believe.

Language according to Turbayne

Language is the conventional use of signs functioning not only and not chiefly to communicate information but also to arouse emotion and direct action.

—Colin Turbayne

Language for Turbayne is a system of signs and things signified. Signification happens through association, not through physical causality or direct reference to objects. Signs are not related to things by identity, picturing or any kind of necessary connection. Instead, the work is done by association, regularity and convenience. When we learn the word “mother” through ostensive definition, we come to associate the sound of the word with the person indicated.

Convenience includes cases where different things get the same names because of having similar properties or because they are conveniently situated together in time or space. In certain cases, we give a sign the same name as the thing it signifies. For example, we give the marks “d o g” the same name “dog” that we give the animal. Turbayne regards names like this as a species of metaphor.

Ordinary language contains literal terms, metaphors that are evident and metaphors that are hidden or non-evident. The degree of hidden-ness has a lot to do with the age of the metaphor. Newer metaphors tend to be more obvious.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Three stages of metaphor

Turbayne accounts for the differences in seeming literality by giving a kind of biography of metaphor. A metaphor passes through three stages, he says.

The first stage occurs when the metaphor is first coined. It’s fresh, live. On the very first use of a new metaphor, the audience may consider it clever, creative, poetic or just plain wrong, as when a child calls a camel a “dog”.

If the usage catches on, the metaphor begins its second stage. This is when it is used knowingly as a metaphor. Structural engineers may write about “metal fatigue” and include quotation marks.

The third stage is when the metaphor shades into literal usage. We forget that it’s a metaphor. It has passed from fresh to live to dead. We speak of the mind comprehending objects or thoughts residing in the mind. “Metal fatigue” may become such a commonplace term that it loses its quotation marks. It may enter the vocabulary of transportation safety investigators, as in this recent headline:

Crash landing of commuter airline in Georgia caused by metal fatigue leading to loss of prop blade, Safety Board finds.

—from a U.S. Government website

From metaphor to myth

A metaphor used in a new scientific theory might even grow into an entire myth, if the theory becomes dominant. This is the “myth of metaphor”. And it’s just what happened, Turbayne argues, with René Descartes’ “machine” metaphor.

I have described the Earth and the whole visible universe as if it were a machine, having regard only to the shape and movement of its parts.

—René Descartes

For Descartes, a machine is geometry in motion. He also said, “My physics are nothing but geometry.” He wasn’t the first to employ the geometry metaphor for the world. He was preceded by Pythagoras, Archimedes and Euclid, and then followed by John Locke, Blaise Pascal and Isaac Newton. But he was perhaps more aware that he was using metaphor.

Turbayne also extends the idea of metaphor in an unusual way, by applying it to non-verbal experiences like vision. He sees the world of vision and other senses as a language consisting of signs and things signified. A visual shape can be a sign and a tactile sensation can be the thing signified. The relation between the two is based on association and convenience, and Turbayne often speaks of the connection as metaphorical as well. A red and white octagon (stop sign) can be a metaphor for the sound (in English) “STOP”.

In the second half of the book, Turbayne develops the “language” metaphor for vision and, by implication, for all sensory modalities. He argues in what could be considered a multi-chapter battle of the metaphors that “vision-as-language” is a more useful metaphor than “vision-as-geometry”. Why more useful? Because the language metaphor accounts for perceptual phenomena such as illusion and the famous Molyneux problem more fruitfully than the geometric model[4.].

We don’t have the space to cover Turbayne’s battle but I recommend it. It’s an illuminating example of how to see science through the lens of metaphor.

Taking metaphors literally

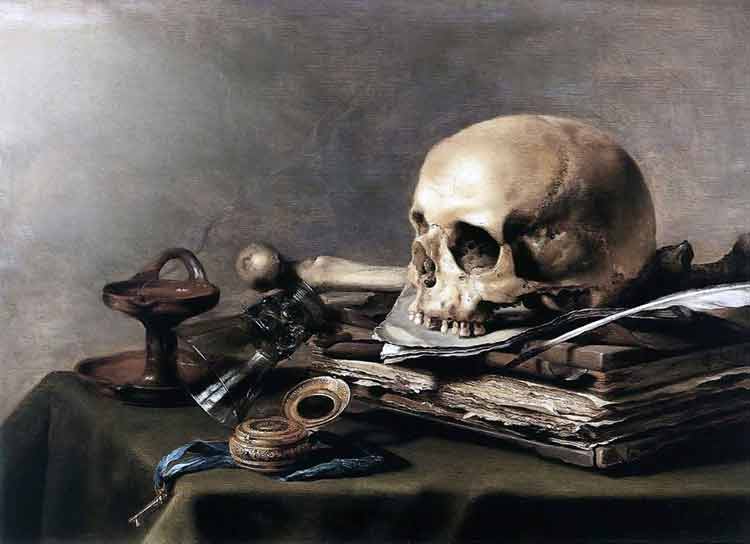

… enthralled by his own metaphor, [Descartes] mistook the mask for the face and consequently bequeathed to posterity more than a world view. He bequeathed a world.

—Colin Turbayne

What is it like to take a metaphor literally? Turbayne gives an example of an extended metaphor we may be taking seriously: the “machine” model of the world and its corollary, the “geometry” model. What started as a self-conscious metaphor for Descartes has evolved over the years to become a literal world view.

Turbayne narrates the rise of the geometry model, which began to gain prominence in the seventeenth century. According to this model, the world is made up of external objects. These objects are said to have certain attributes, such as shape, angles, extension, colour, size and patterns of movement. Our senses reach out and grasp these attributes and transmit them to the mind, which processes the information and forms an internal mirror image of the external object. Part of the processing includes geometry. Using geometric phenomena like visual rays, objective distances and angles, the mind is said to calculate distance, size and motion.

This is such an authoritative model that it probably isn’t seen as a model at all but rather the literal truth about the world. Turbayne credits Descartes and Newton as the most influential proponents of this model. About these philosophers, Turbayne says:

Together they have founded a church, more powerful than that founded by Peter and Paul, whose dogmas are now so entrenched that anyone who tries to re-allocate the facts is guilty of more than heresy; he is opposing scientific truth.

—Colin Turbayne

As we recall, this type of account began as a living metaphor. Descartes had acknowledged this when he wrote, “I have described the Earth … as if it were a machine.” But per Turbayne, the metaphor has hardened into literal, even dogmatic truth.

Turbayne gets creative in coming up with other ways to describe taking metaphors literally. He says that it is to be victimized. It is confusion, not fusion. It is sort-trespassing, not sort-crossing. It mistakes the mask for the face, theory for fact, and procedure for process. It is to be an inhabitant of the Emerald City when we could be the Wizard of Oz.

As I mentioned above, Turbayne never tells us exactly why we shouldn’t take metaphors literally. But if we read between the lines, we gather that avoiding this mistake opens up a wonderful freedom, which in Turbayne’s own case leads to the possibility of God in the midst of things.

These questions may be familiar to students of spiritual or human enquiry. Forms of enquiry such as Vedanta, Madhyamika, Taoism and even Deconstruction or Social Construction devote at least some time to uncovering metaphor in order to free us from attachment to conceptuality. According to these paths, our attachment consists of believing that some conceptual account of the world is literally or objectively true. These paths give us various ways of transcending the attachment. In fact, even their own accounts are pragmatic and provisional, not to be taken as ultimately true.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Finding the metaphor

Some metaphors are evident, such as “iron curtain”. But some are hidden from view, such as “we can estimate the distance [of an object] by means of … the size of the image on the retina”[5.]. These metaphors tend to be the ones we have forgotten about. So how can we identify them so we can begin to recognize their non-literal nature?

A major clue is the crossing of sorts or mixing of categories. When you look at an account of the world, does it use physical categories to describe mental phenomena? Turbayne gives several examples, such as “the motion of the will”, “ideas in the mind” and “the mind is behaviour”[6.].

Another clue is found in accounts of reality that project our own cognitive or investigatory procedures upon natural processes. This is the problem exemplified in the quote above, which states that we estimate the distance of an object by means of the size of an image on our retina. The size of an image on our retina is part of a procedure used in an explanation of vision but it is not part of the process of vision. We don’t see images on our own retina.

Another example comes from deductive logic. Some philosophers have held that we can deduce effects from causes in the world the same way we deduce conclusions from premises in a logical argument.

… we deduce an account of the effects from the causes.

—René Descartes

This is an example of assigning our own logical procedures to natural process and confusing the things of logic with the logic of things.

If you come across accounts with sort-crossings like these, you can be sure there’s a metaphor close by. Turbayne suggests that when you find a candidate metaphor, you test it. Play with the metaphor, extend it, exaggerate it:

- Men and timber wolves are wolves

- God and Frank Lloyd Wright are architects

- Ideas and apple seeds are in the mind

- The will and the train are in motion

If your playful sentences give you the mildly dissonant feeling that words are being used in different senses, then you are already freeing yourself from victimization by metaphor.

Getting to the literal truth

The sciences now have masks on them. If the masks where taken off they would appear supremely beautiful.

—René Descartes

When I first read the book, I couldn’t wait to get to this part. I was starting to feel impatient with all the talk about metaphors. I was thinking, “Why doesn’t he tell us what’s literally true?” I was sure that Turbayne was going to reveal what the literal truth was, in order to clarify why by contrast all these other phrases were metaphors.

Indeed, “taking off the masks”, or at least trying, is a pivotal part of Turbayne’s strategy. He goes through the motions to show us that it can’t be done. He gives us the example of a popular modern philosopher who thinks he is correcting a myth and uncovering the literal truth but unbeknownst to himself, fails.

In his well-regarded book The Concept of Mind (1949), Gilbert Ryle explodes the dualistic Cartesian myth of a mind in a body or as he says, a “Ghost in the Machine”. The phrase is Ryle’s playful extension of the Cartesian myth, which Ryle sees as false.

Ryle seeks to correct what he calls a category mistake. He accuses Descartes of presenting observable behaviour in terms of the wrong category, as imaginary, unobservable entities such as “mind”, “will”, “volition” and “vanity”. The problem for Ryle is that Descartes treats these imaginary entities as real causes of physical effects, as though “the will” can move an arm or leg. But causation doesn’t work this way, says Ryle. Mythical objects can’t produce physical effects.

After diagnosing Descartes’ problem, Ryle attempts to address the category mistake. He tries to re-allocate the facts to their proper categories by coming up with true explanations. Ryle’s explanations include modern concepts, such as inductive logic, “probabilities”, “dispositions”, “propensities” and “tendencies”. For example, “vanity” is re-allocated as “a tendency to boast”. The “mind” is re-allocated as “my ability and proneness to do certain sorts of things”.

Turbayne’s point is that Ryle’s explanation is every bit as metaphorical as Descartes’. In fact, Descartes was evidently more aware of his own metaphors than Ryle was. Ryle’s “dispositions” and “tendencies” are just as unobservable and mythical as Descartes’ “mind” and “will”.

Ryle had in effect come to believe in the literal truth of his own metaphors. For Turbayne, this means he became victimized by them:

The conclusion of this section is a simple one. The attempt to re-allocate the facts by restoring them to where they ‘actually belong’ is vain.

—Colin Turbayne

Turbayne concludes that any account of the facts is due to some metaphorical filter we bring to the observations. Any account is inevitably a theory laden with metaphor. Any theory is vulnerable to having its terms deconstructed and its metaphors uncovered.

None of [the theories] can validly claim to provide the correct allocation of the facts. Has God vouchsafed to any one of them a special revelation?

—Colin Turbayne

This section is in Chapter III of the book and it’s Turbayne’s first mention of God in his own authorial voice. He will return to the notion of God at the end of the book.

Back to metaphor but with awareness

After showing that we can’t get rid of metaphors and replace them with the literal truth, Turbayne suggests that we use metaphors but use them knowingly. We can use the same old ones or create new ones. The point is not to fall into the belief that reality is objectively a certain way, just because a description is phrased that way.

If all accounts are unavoidably dependent on metaphor, how do we decide which metaphors to use? We can’t choose based on their proximity to literal truth but Turbayne gives us other criteria. Some metaphors might be more appealing. Some might be more productive in terms of suggesting new directions for research. Some might allow for more reliable prediction or prove more fruitful guides to action.

In other words, we do have criteria. It’s just that they are aesthetic and pragmatic criteria, not based on an unmetaphorical access to literal truth.

The freedom of nonconceptual space

Why are we attached to some particular conceptual account of how things are? Perhaps because it makes us feel safe, secure, grounded and in touch with reality as (we think) it “really is”. Our attachment is supplied in large part by our idea that an account is literally true.

But when the very idea of a literally true account of the world is exploded, we enter a vast expanse that is free from conceptual attachment. In this freedom, we don’t feel out of touch with reality. According to Turbayne’s metaphorical way, we won’t feel that one account is uniquely true and its competitors false.

Turbayne’s nonconceptual space is also implied by the Buddhist realization of the emptiness of emptiness. This is the meta-level insight that even though “emptiness” is a supremely valuable experiential tool, it isn’t a literal or empirical truth. Emptiness too is a metaphor that can be played with in the Turbaynean way:

- My cup is empty of coffee and inherent existence

A Turbaynean Buddhist might say, when we realize that that “emptiness” is metaphorical, we thereby realize that it’s empty. In a good way.

This nonconceptual space also resembles the notion of “joyful irony” that I discuss in Emptiness and Joyful Freedom and After Awareness [7.]. The “joy” is the open-hearted love that is enabled by one’s path of compassion and enquiry, and the “irony” is one’s freedom from conceptual attachment.

We find freedom and creativity in this nonconceptual space. Here, Turbayne reaches for the divine:

If our most holy religion is founded upon faith and not reason … then, other scientific things being equal, it would be more appropriate for us to choose that metaphor that fits with our religion.

—Colin Turbayne

Turbayne’s more appropriate metaphor is not the machine but language. Turbayne prefers to treat the world as though it is a verbal and sensory language with God as its author.

I can argue from the signs, the things signified and the rules of grammar to the conclusion that the events in nature are the language of the author of nature. In which case I have another a posteriori argument for the existence and nature of God.

—Colin Turbayne

Turbayne chooses God but we don’t have to. The nonconceptual space has infinite joyful room for our creativity.

Footnotes

- The Myth of Metaphor, by Colin M. Turbayne. xv, 241 pp. Foreword 1 by Morse Peckham. Foreword 2 by Foster Tait. Appendix, “Models, Metaphors, and Formal Interpretation” by Rolfe Eberle. First published 1962. Revised ed., Columbia, S. C: University of South Carolina Press (1970).

- See his Metaphors for the Mind (1991).

- This definition, “the presentation of the facts of one category in the idioms appropriate to another”, comes from Gilbert Ryle’s Concept of Mind (1949). For Ryle, it is not the definition of metaphor. It is the definition of “category mistake”, where we mix things together that should be kept in their separate categories. But then Ryle was discussing literal declarative statements, not figurative language.

- The Molyneux problem is named after William Molyneux (1656-1698), a natural philosopher who posed this question: if a man, born blind, has become able to distinguish a cube from a sphere using the sense of touch, then what happens when his sight is restored? Without receiving any extra training or conditioning, will he be able to ascertain through vision alone which object is the cube and which is the sphere? The question was considered by Locke, Berkeley and other seventeenth-century philosophers before there were empirical test cases. Turbayne argues that the geometric model of vision suggests that the man would be able to distinguish the two objects and that the language model suggests that he would not. Since the seventeenth century there have been several medical cases in which vision was restored for patients born blind. In most cases, research has found that specific vision training is required before visual objects begin taking shape for the newly sighted. This supports Turbayne’s argument.

- From Hermann von Helmholtz, Treatise on Physiological Optics (1925).

- See also the section called “The Container Metaphor in Western Culture” in my book The Direct Path (2012), published by Non-Duality Press.

- Published 2013 and 2016 respectively by Non-Duality Press.